What the dust in your house reveals about you

- Share via

Even if you live by yourself, you do not live alone.

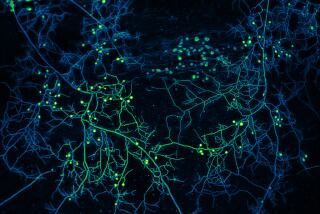

In a new analysis of dust samples collected from 1,200 homes across the United States, researchers report that most of us cohabitate with a few thousand species of bacteria and about 2,000 species of fungi.

But don’t reach for the scrub brush and disinfectant just yet.

“I don’t want any readers to be paranoid about this,” said Noah Fierer, a microbial ecologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “Most of the organisms are completely innocuous, and some may be beneficial.”

In a study published this week in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Fierer and his colleagues report that these microscopic communities can also reveal telling details about the people they live with.

It turns out that the specific composition of a home’s bacterial community changes depending on whether there is a dog or cat in the household, as well as the ratio of men to women in the home. The composition of the fungi community, on the other hand, reflects the climate and geographical region where a person lives.

“If you want to change the types of fungi you are exposed to in your home, then it is best to move to a different home (preferably far away),” the authors wrote. “If you want to change your bacterial exposures, then you just have to change who you live with.”

To come to these conclusions, the research team reached out to citizen scientists across the country through a websitehttps://www.yourwildlife.org/ called Your Wild Life, which helps facilitate the study of microbes. Volunteers were sent a pair of sterile cotton-tipped swabs (they looked like long Q-Tips) and asked to swipe one above the trim of an interior door and the other above the trim of an exterior door.

“The reason we had them sample there is because people don’t touch it, and it is not typically cleaned very often,” Fierer said.

Household dust is made up of a hodgepodge of insect parts, pollen, dead human cells, drywall powder, carpet fibers and soil particles, among other ingredients. There’s a fair amount of airborne bacteria and fungi mixed in as well.

The double sampling allowed researchers to see whether the microbial populations differed between the inside and outside.

After dusting for science, participants were asked to complete a survey that included questions about the age of their house, how many bedrooms it had, whether it had a basement or carpeting, how often the windows were left open and whether insecticides or mold-fighting products had been used recently.

“We asked all sorts of questions, but most of them were not very predictive,” Fierer said.

Still, some patterns did emerge.

The researchers found that most of the fungi in our homes originates outdoors and probably comes inside via soil particles or as airborne spores. That’s why people who live in the same geographical area are likely to have the same types of fungi in their houses.

The same is not true for bacteria, however. The team found a greater discrepancy between the communities of bacteria in and out of the home, with the indoor-dwelling populations being significantly more diverse than the outside populations.

The geographic location of a house did not appear to influence its bacterial community, the researchers wrote. But the presence of pets did.

“The two main things we noticed were whether the person lived with a dog or a cat,” Fierer said.

He added that the team was also able to predict the ratio of women to men in a household based on the bacteria composition, although this effect was more subtle.

The study did have a few limitations. For one, the researchers don’t know how long the dust in the samples had been accumulating inside and outside the homes. It’s possible that some samples represented a month or two of microbial activity, while other samples covered a period of years.

Also, all of the homes had at least one male and one female. Fierer said the team is working on a follow-up study in single-sex college dorm rooms to see how the composition of microbes differs in all-female and all-male environments.

Previous studies had suggested that bacterial communities in homes are associated with people and their pets, but nobody had ever looked at such a large and geographically diverse set of samples before.

“This is the first large-scale study that supports what we already know about the microbes in the home environment,” said Jack Gilbert, a microbiologist with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago. “It gives us more power to understand the effects of different factors on these communities.”

Fierer said the data from his study would be made public online so other researchers can use it. He added that the research would not have been possible without the help of unpaid citizen scientists.

“Ideally, we would have a team of scientists all trained to sample in the exact same way, but we would never have had the funding to do that,” he said. “We could never have done this research without our army of volunteers.”

Twitter: @DeborahNetburn