Cheating students more likely to want government jobs, study finds

- Share via

College students who cheated on a simple task were more likely to want government jobs, researchers from Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania found in a study of hundreds of students in Bangalore, India.

Their results, recently released as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, suggest that one of the contributing forces behind government corruption could be who gets into government work in the first place.

For instance, “if people have the view that jobs in government are corrupt, people who are honest might not want to get into that system,” said Rema Hanna, an associate professor at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. To combat that problem, governments may need to find new ways to screen people seeking jobs, she said.

Researchers ran a series of experiments with more than 600 students finishing up college in India. In one task, students had to privately roll a die and report what number they got. The higher the number, the more they would get paid. Each student rolled the die 42 times.

Although researchers do not know for sure if any one student lied, they could tell whether the numbers each person reported were wildly different than what would turn up randomly -- in other words, whether there were a suspiciously high number of 5s and 6s in their results.

Cheating seemed to be rampant: More than a third of students had scores that fell in the top 1% of the predicted distribution, researchers found. Students who apparently cheated were 6.3% more likely to say they wanted to work in government, the researchers found.

“Overall, we find that dishonest individuals -- as measured by the dice task -- prefer to enter government service,” wrote Hanna and coauthor Shing-yi Wang, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

They added, “Importantly, we show that cheating on this task is also predictive of fraudulent behaviors by real government officials.”

The same test, given to a smaller set of government nurses, showed that those who appear to have cheated with the dice were also more likely to skip work. Previous studies suggest that the bulk of such absenteeism is fraudulent, Hanna said.

Researchers also ran other tests to gauge character: In another experiment, students played a game in which they could send a message anonymously to another player, either telling them honestly what move would earn them more money, or dishonestly nudging them toward a worse choice. Tricking the other student would help them gain more money.

A third test asked students to divide up a sum of rupees between themselves and a charity of their choice; for each rupee they chose to donate, the amount given to charity would double. Still other tests measured their memory and cognitive ability, or quizzed students about whether they would cheat on exams or believed that most businesses paid bribes.

Their findings differed from test to test: In the charity test, keeping more rupees for themselves was more common among government worker wannabes. However, lying during the message game seemed to have no correlation with whether students wanted to go into government work.

Researchers speculated that the difference between that game and the dice test, both of which measure dishonesty, could be that students felt differently about stealing from other students than “the experimenters” who ran the dice game. Hanna added that it’s harder to tell if a particular person has cheated during the dice game, which might affect their actions.

Surveying people about corruption also did little to predict whether people were prone to lie in real life, the researchers concluded -- a troubling finding for governments that have folded such questions into job screening. Nor did ability seem to make a difference.

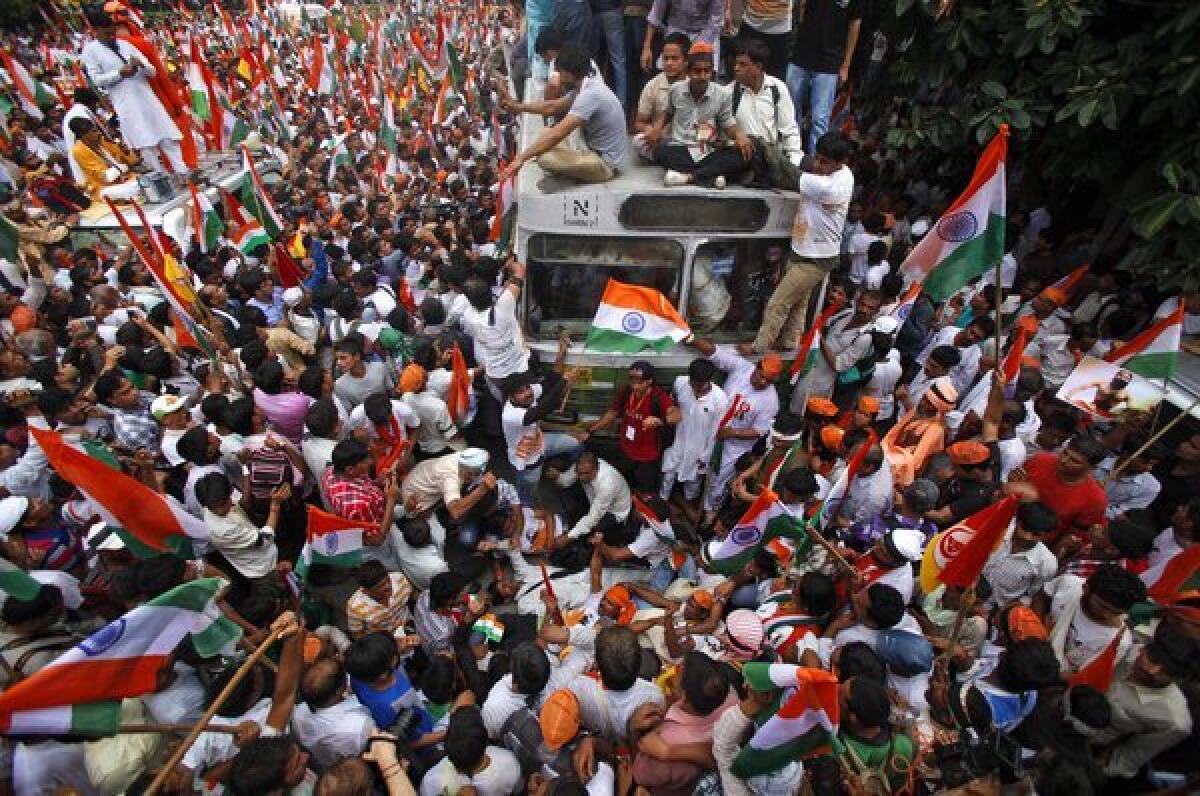

Complaints of corruption have stirred up past scandals in India, which ranked 94th out of 176 countries and territories in perceived corruption, according to a Transparency International index. Hanna said she was curious whether the same results turn up in other countries where government workers get higher wages and corruption is seen as less of a problem.

ALSO:

Volcano discovery hints at fire below ice in Antarctica

Illinois twisters: ‘Whole neighborhoods where there’s nothing left’

Multiple military deployments in families may raise teen suicide risk