Granite on Mars? Red Planet gets weirder and weirder

- Share via

As NASA’s MAVEN mission heads toward Mars, scientists say they’ve discovered highly unusual, light-colored rock on the mostly dark-toned Red Planet – and two teams have dueling ideas of what such pale rock could be. Could it be granite, the stuff found in fancy kitchen counter tops on Earth? Or could it be anorthosite, the rock that characterizes the bright highlands of the moon?

Either way, the two papers published in Nature Geoscience indicate that Mars’ inner workings may have been more complicated, and its rock collection more diverse, than planetary scientists once thought.

Mars is mostly covered in dark basaltic rock, and doesn’t have a lot of the lighter rock (such as granite) that comes about through plate tectonics, like on Earth. That’s because Earth had enough large-scale, sustained geophysical activity that the cooling magma had time to fractionate – that is, denser and lighter types of rock would slowly separate from each other over time, at different pressures and temperatures. Mars didn’t have the same complex processes that gave rise to these “evolved magmas,” scientists thought.

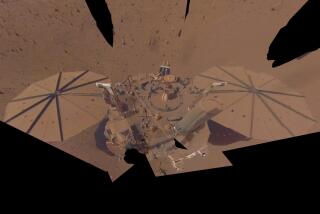

But NASA’s Curiosity rover recently picked up signs of lighter rock as it explored Gale Crater, and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has also found signs of paler areas in several different spots in the southern highlands. The European team and the Georgia Tech teams each picked out their favorites to study.

The strange part is that the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shouldn’t have been able to see these felsic rocks, called plagioclase feldspars, at all. Its infrared images are designed to pick up signs of iron and water – which are typically found in basaltic rock and clays, not so much in felsic rock like plagioclase or quartz. If the orbiter picked up plagioclase, there may have been a little iron in it – but more importantly, there was probably a heck of a lot of it.

“The fact that clear-cut signatures of plagioclase were detected in two independent studies implies that no more than 5% of the target rocks are composed of iron-rich minerals typical of basalt,” Briony Horgan of Arizona State University wrote in a commentary on the papers. “The remaining 95% of the rocks must be composed of plagioclase and other undetected silica-rich phases such as quartz.”

There’s the rub: The spacecraft’s instruments can’t distinguish between what’s plagioclase feldspar and what’s quartz, and that’s where the two papers differ.

The Georgia Tech teams thinks the light-colored rock they analyzed may contain both feldspar and quartz – which would make it granite (or something close to it). The European team leans more toward the idea that the rocks may be almost pure plagioclase – which could make it a rock called anorthosite, which is commonly found on the moon.

Those two types of rocks would theoretically have been created by different processes, probably in localized areas. But either way, whoever’s right, the findings add to a growing body of evidence that Mars’ geophysical history may have been a lot more complicated than once thought.

“We see evidence for a more evolved planet,” Curiosity’s lead scientist John Grotzinger said a few months back while describing a very dark, but also strangely evolved, rock called Jake Matijevic that was described in Science in September. “So it looks like it was headed in more of a direction like Earth.”

ALSO:

Puffy clouds, clear lakes: NASA’s MAVEN hunts for vanished Martian atmosphere

No place like home? Milky Way may host billions of ‘Earth-like’ planets

Trees marshall ant army to fight leaf-munching invaders