Nearly half of Americans with high cholesterol are not taking medication, study says

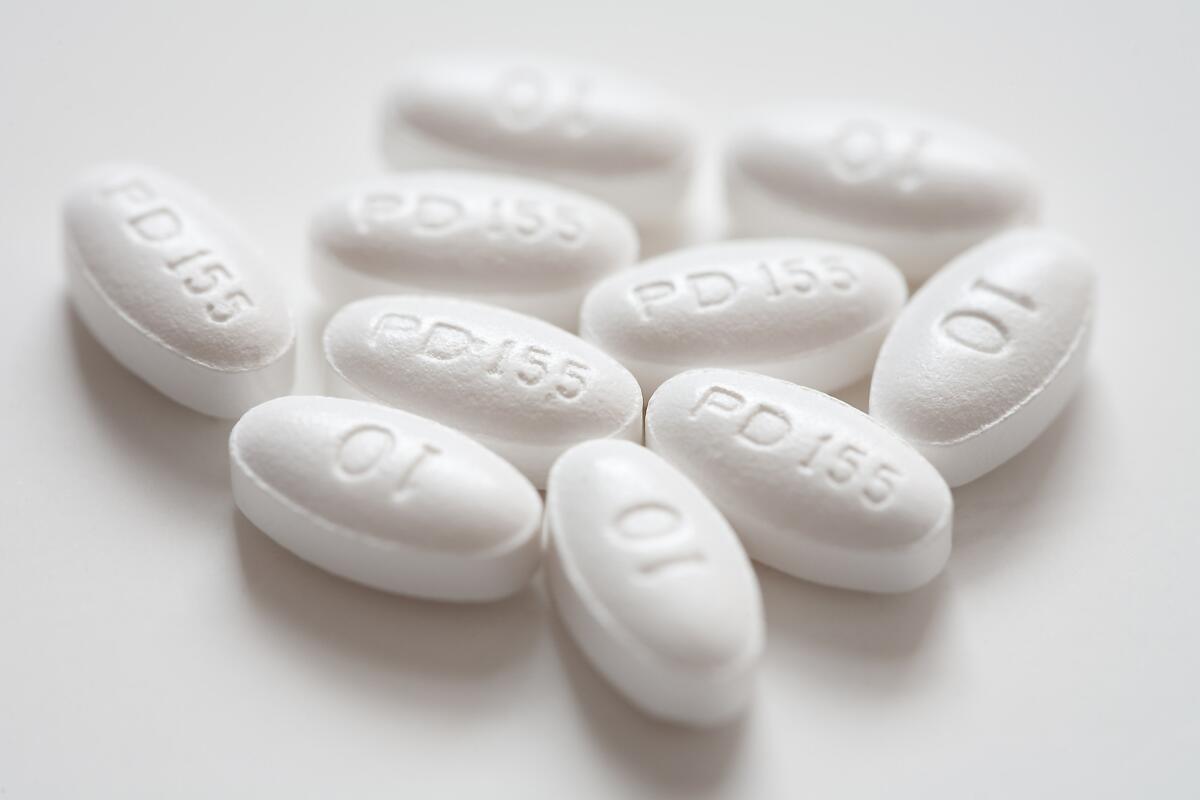

Lipitor is a synthetic lipid–lowering agent created to reduce elevated blood cholesterol levels when accompanied with diet changes. A new study shows that nearly half of Americans who have high cholesterol are not taking medication.

- Share via

Nearly half of Americans whose cholesterol readings put them at higher risk of heart attack or stroke are not taking medication to drive down that risk, says a new study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new study makes clear that public health authorities bent on preventing heart disease and stroke have their pick of a lot of low-hanging fruit. Worrisome cholesterol numbers are a strong risk factor in cardiovascular disease, which contributes to one in three deaths in the United States. And cholesterol-lowering treatment--generally with a low-cost statin medication--has been shown to drive down rates of heart attack and stroke.

All told, 44.5% of American adults likely to benefit from cholesterol-lowering drugs were not on one. But the cholesterol treatment gaps observed by the CDC were far more pronounced among minorities in the United States than among white Americans.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

African Americans are most likely to have health conditions that make them candidates for cholesterol-lowering medications: 39.5% of American blacks are considered “eligible” for such treatment. But 54% of eligible U.S. blacks were not taking medications to limit their risk.

Among whites, 38.4% are eligible for such drugs, and 42% of that group took no cholesterol-lowering medication.

Among Mexican American adults, it is thought that roughly a quarter should be taking a cholesterol-lowering drug. But 52.9% of them are not taking one.

Adult women who were eligible to take prescription cholesterol drugs were more likely than eligible men to be taking them (58.6% versus 53.9%). And among African Americans with no regular source of medical care, 94.3% of those eligible failed to take potentially life-saving medication.

Side effects of cholesterol-lowering medications prompt some resistance among patients. Among those taking statin medications--the frontline treatment for high cholesterol--roughly one in 10 develops significant muscle pain and fatigue, and about one in 100 develops diabetes.

But the latest research found that lifestyle changes that can help reduce cardiovascular risk--and which have few worrisome side effects--were also not widely followed by adults who could benefit from them. Among the 78.1 million adult Americans who were either taking the medications or considered candidates for cholesterol-lowering treatment, 46.6% reported they had made lifestyle changes such as exercising more, losing weight and eating a more heart-healthy diet.

Some 37.1% reported making lifestyle modifications and taking medication. But 35.5% reported they did neither.

Nearly 800,000 people die of cardiovascular disease in the United States each year, making strokes and heart disease by far the largest killer of Americans.

Between 2005 and 2012, an average of 78.1 million Americans--close to 37% of the adult population--yearly were either taking a prescription medication to improve their cholesterol profile or would, by current standards, be eligible to do so.

In 2013, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Assn. issued new guidelines defining who should take the medications. More expansive than those in place previously, those guidelines added as many as 10 million American adults who were previously not candidates for cholesterol drugs to the pool of those eligible.

The new guidelines--used in the current estimates--recommended cholesterol-lowering treatment for all adults with a previous history of cardiovascular disease, for most of those with diabetes, and for adults 40 to 75 with other cardiovascular risk factors and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol readings between 70 and 189 mg/dL.

A study published in JAMA in July suggested that strict adherence to 2013 guidelines could prevent 41,000 to 63,000 heart attacks and strokes over 10 years.

The new numbers underscore that efforts to drive down numbers of heart attacks and strokes should focus patient education and cholesterol management programs on populations in which treatment rates are especially low, said Dr. Carla Mercado, a scientist in CDC’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Couch potato in your 20s? Your brain may suffer in your 50s, study finds

Rebel Paleolithic artist breaks the rules, draws a campsite 13,800 years ago

If you’re having trouble quitting smoking, maybe you can blame your DNA