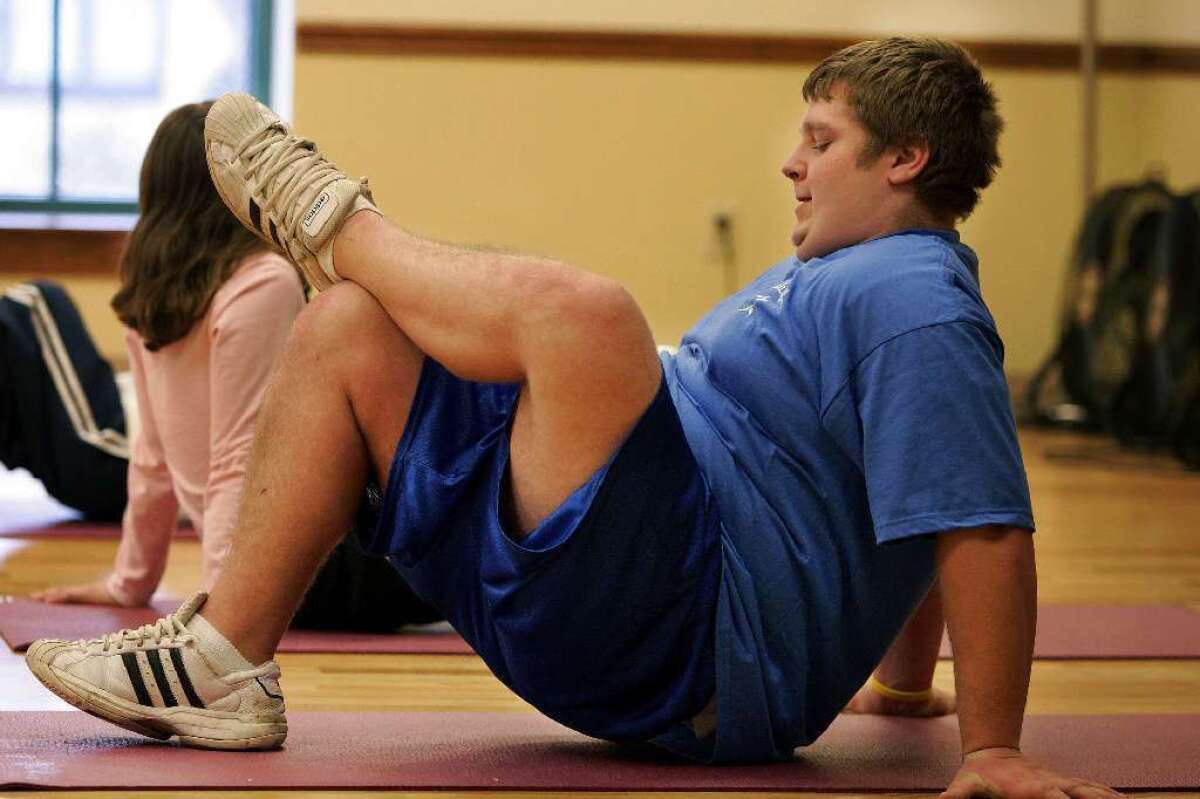

Overweight and obese kids are in denial about their weight, CDC says

- Share via

New government data suggest a non-medical cause of America’s childhood obesity crisis: denial.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 48% of obese boys and 36% of obese girls think their weight is “about right.” Among kids and teens who were merely overweight, 81% of boys and 71% of girls also judged their weight to be “about right.”

Those figures are based on interviews with American children who were between the ages of 8 and 15 during the years 2005 through 2012. As part of the CDC’s ongoing National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, they had their height and weight measured and they answered questions from interviewers. Among them: “Do you consider yourself now to be fat or overweight, too thin or about the right weight?”

Overall, 30.2% of the kids gave an answer that wasn’t in line with their actual body mass index, according to the report from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. That corresponds to about 9.1 million American kids who have the wrong idea about their weight status.

Roughly 20% of these kids had a healthy weight but mistakenly thought they were either too thin or too fat. But the overwhelming majority were low-balling their weight.

Boys were more likely than girls to think their extra pounds were normal, the CDC researchers found. In addition, Mexican American kids were more likely to suffer from “weight status misperception” compared with African Americans, who in turn were more likely to have it than white kids. The prevalences for the three groups were 34.4%, 34% and 27.7%, respectively. (Figures for Asian Americans weren’t reported.)

Children between the ages of 8 and 11 were more likely to get their weight status wrong (33%) than kids between the ages of 12 and 15 (27%). Also, the higher a child’s family income, the less likely he or she was to have the wrong idea about his or her body weight.

All of this matters because overweight and obese kids aren’t likely to slim down if they think their weight is just fine. Kids who are overweight or obese are likely to carry those extra pounds with them into adulthood, leading to a host of health problems that add up to $19,000 in extra medical costs over a lifetime.

“Understanding the prevalence of weight status misperception among U.S. children and adolescents may help inform public health interventions,” the CDC researchers wrote.

By definition almost all kids – those between the 5th percentile to just under the 85th percentile – are considered to have a “healthy weight.” Only kids with a BMI that puts them at or above the 85th percentile to just under the 95th percentile are officially “overweight,” and those at or above the 95th percentile are classified as “obese.” In addition, kids below the 5th percentile are considered “underweight.”

(For adults, people with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 are considered “normal,” people between 25 and 29.9 are “overweight,” people above 30 are “obese” and people below 18.5 are “underweight. You can use this online calculator from the National Institutes of Health to learn yours.)

Researchers documented a similar problem in adults back in 2010, though they called it “body size misperception” in a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Parents can also be wrong about the weight status of their kids. A 2012 study in the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine reported that about two-thirds of low-income mothers incorrectly believed their toddlers were too small.

Last month, researchers from UC San Diego and Brown University reported that 31% of parents whose children were being treated in a hospital obesity clinic thought their kids’ health was “excellent” or “very good.” That study was published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

For more news about science and medical research, follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.