An outbreak in Brazil has U.S. health experts wondering if yellow fever could be the next Zika

An essay by the New England Journal of Medicine warns it can kill as many as 10% of those infected. (March 9, 2017)

- Share via

Yellow fever has broken out in the jungles outside Brazil’s most densely-populated cities, raising a frightening but still remote possibility: an epidemic that could decimate that country’s population and spread throughout the Americas, including the United States.

In an essay rushed into print by the New England Journal of Medicine on Wednesday, two doctors from the National Institutes of Health warn that cases of yellow fever, which can kill as many as 10% of those infected, have seen an unusual spike in the last few weeks in several rural areas of Brazil.

Those outbreaks have been limited to places where there aren’t enough people or virus-spreading mosquitoes to fuel a rapid run-up in transmission. But they are on the edge of major urban areas where residents are largely unvaccinated, and where both humans and insects are packed densely enough to accelerate the disease’s spread.

It’s a perilous moment, made more so by the fact that, while an effective vaccine against yellow fever has been around since 1937, worldwide stockpiles are all but depleted. In a series of yellow fever outbreaks in Angola and Democratic Republic of Congo two years ago, public health officials ran so short of the vaccine that they resorted to giving each person one-fifth of a dose.

Only a few companies worldwide manufacture the vaccine, and making additional doses takes a long time, said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and coauthor of the new essay.

In the virtual absence of stockpiled vaccine, wrote Fauci and Dr. Catharine I. Paules, “early identification of cases and rapid implementation of public health management and prevention strategies, such as mosquito control and appropriate vaccination, are critical” to preventing an explosion of yellow fever.

In an interview, Fauci said he considered it “unlikely” that an outbreak that has been confined to Brazil’s forest communities would spread to that country’s cities and catch fire.

With more than 1,000 suspected cases in Brazil and 371 confirmed by blood tests, “it’s not critical yet in Brazil,” he said. But he would worry, he added, if cases of yellow fever begin to turn up in such cities as Sao Paolo, Rio de Janeiro or Brazilia among people who have not come in from the jungles.

Fauci said it was important that his office “puts it on the radar screens” of both public health authorities and physicians. Most doctors have never seen yellow fever, which made its most frightening mark in the United States in Philadelphia in the fall of 1793. Brought in by people fleeing an epidemic in the Caribbean, yellow fever swept through the city, killing roughly 1 in 10 inhabitants.

Yellow fever is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which circulates in parts of the southern United States. But for yellow fever to gain a foothold in this country, many of those mosquitoes would need to feast on the blood of people who had been infected elsewhere and traveled here. Then, the mosquitoes would have to quickly move on to transmit the virus to others nearby. That chain of events would require a density of mosquitoes, infected travelers and innocent bystanders that, while possible, is improbable.

“In an era of frequent international travel, any marked increase in domestic cases in Brazil raises the possibility of travel-related cases and local transmission in regions where yellow fever is not endemic,” Fauci and Paules wrote.

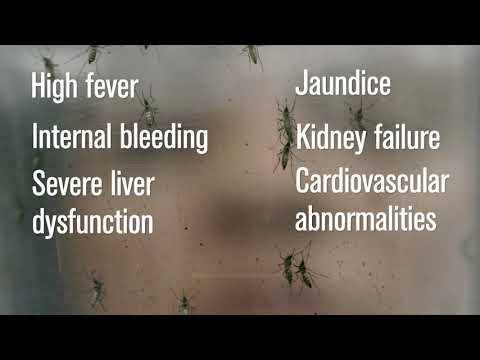

Doctors in the United States should be asking for travel histories from any patients who turn up after a brief, mild illness appeared to go away, but was quickly followed by the hallmark symptoms of yellow fever’s “intoxication stage” — high fevers, internal bleeding, severe liver dysfunction and jaundice (hence the name “yellow fever”), kidney failure, cardiovascular abnormalities, central nervous system dysfunction and shock.

Fauci and Paules wrote that it was “highly unlikely that we will see yellow fever outbreaks in the continental United States.”

But, they added, “it is possible that travel-related cases of yellow fever could occur, with brief periods of local transmission in warmer regions such as the Gulf Coast states, where A. aegypti mosquitoes are prevalent.”

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, acknowledged that while it was too early to panic, the prospect of “urbanized” yellow fever was one that strikes fear in the hearts of public health officials.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito that spreads yellow fever “does very well in urban areas,” where trash and discarded plastic offer ideal breeding sites and humans are readily available to bite. In such circumstances, it doesn’t take too many people infected with yellow fever to feed an army of mosquitoes, who will then carry the virus on to the next group, and the next, said Osterholm, the author of a forthcoming book, ”Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs.”

“It’s like throwing a yellow fever match into a gas tanker. Those are the perfect ingredients for yellow fever explosion,” he said.

If a vaccine is largely absent, the resulting conflagration can spread unchecked, he added.

Even if Brazil’s yellow fever outbreaks go to ground in the jungle, Fauci said the scenario now unfolding “reminds us of the things we need” to see potentially deadly epidemics coming — and respond to head them off.

Those include good surveillance by doctors and public health officials to detect even small outbreaks; the capacity to ramp up vaccine production quickly; and a “public health emergency fund” so that government officials can take urgent measures to stamp out disease transmission before an epidemic takes hold.

ALSO

As obesity keeps rising, more Americans are just giving up

Computers can now challenge — and beat — professional poker players at Texas hold ‘em

Pregnant women with Zika are 20 times more likely to have a baby with a birth defect, CDC says