- Share via

Poor Mt. Disappointment.

Located high in the San Gabriel Mountains, it’s the only peak in the 60-mile-long range with such an unflattering name.

Nearby you might summit Josephine Peak, named for the wife of a federal surveyor, or savor the views from Mt. Markham, named after a former governor.

But Mt. Disappointment honors nobody. It’s jarring. Petty. Mean-spirited.

“It’s not a popular destination,” said Nathan Judy, a spokesman for the U.S. Forest Service.

And yet.

“When I first read there was a mountain called Mt. Disappointment, my immediate reaction was I need to see this place,” said Casey Schreiner, founder of the L.A.-based website ModernHiker.com. “And I don’t think I was the only person who thought that.”

But why Mt. Disappointment?

The answer to that question lies in a little-known tale of ambition, adventure and, yes, disappointment, that would forever alter the nation’s perception of the great American West.

The story begins 150 years ago when George Montague Wheeler, a 27-year-old Army lieutenant, proposed a bold plan to map the whole of the United States west of the 100th meridian — a north-south line that runs through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas.

Wheeler estimated the epic survey would take 15 years to complete and cost no more than $2.5 million (equivalent to about $50 million today).

The proposal, though audacious, was readily accepted by the Army Corps of Engineers, which was eager to get into the land mapping business. Three other major surveys of the West were already underway, but these were led by geologists. Wheeler, a West Point graduate, envisioned a survey that would prioritize topography over geology.

“If you think about the 19th century overall, this is a time when the U.S. is rapidly expanding westward,” said Susan Schulten, a historian at the University of Denver and author of “A History of America in 100 Maps.” “The federal government wants to know what’s out there.”

While Wheeler’s primary goal was to accurately record the valleys, mountains, desert and other land features of the United States, a letter from Andrew A. Humphreys, chief of the Army Corps of Engineers, reveals additional objectives.

These included looking for mineral deposits, locating potential agricultural lands and scouting for sites that would prove useful for military operations.

Humphreys also instructed Wheeler and his men to take stock of the Native American populations they encountered, asking that they gather “numbers, habits and disposition of the Indians who may live in this section.”

The message behind these orders is clear, said Skyler Reidy, a PhD candidate studying California history at USC.

“The incredibly grim side is that they are surveying this land to steal it from native people,” he said. “This is an imperial exercise.”

In 1871, Humphreys authorized Wheeler to employ 10 topographers, geologists, photographers and naturalists as well as up to 20 packers, guides and general laborers. The group was accompanied by more than 50 military men to serve as escorts.

That spring, Wheeler gathered his staff at Elko, Nev. They broke up into small teams to begin the grueling work of mapping more than 72,000 miles of wild terrain in Nevada, California, Utah and Arizona.

But the land wouldn’t give up its secrets easily. Temperatures climbed as high as 118 degrees that summer and several men suffered from overexposure. Some were revived. Others were not so lucky.

By the end of the first season, at least three of Wheeler’s men had died.

Undeterred, Wheeler returned to the field next spring with an even larger group of men.

From 1871 to 1879, Wheeler’s teams explored 21 lakes, followed 90 rivers, recorded the features of 143 mountain ranges and identified 50 thermal and mineral springs in the Southwest. They also discovered dozens of new species, including one bird, eight reptiles, 32 fish, 64 insects and one mollusk.

But back to Mt. Disappointment.

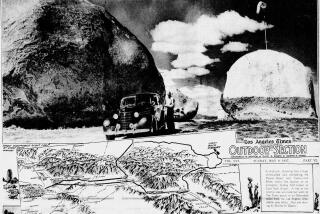

Members of the Wheeler survey began measuring peaks in the San Gabriel Mountains in the summer of 1875.

While surveying the Santa Susana Mountains earlier that year, the group’s leader, Lt. C.W. Whipple, noticed a prominent summit near the front of the San Gabriel range, a few miles northeast of what is now Altadena. Thinking it would make a good triangulation point, he sent his chief topographer and two assistants to set up a survey station on its peak in the dry heat of a July morning.

There was no trail to the top of the 5,963-foot summit and the ascent was brutal.

John Muir, writing for the San Francisco Evening Bulletin just a few years later, described the San Gabriel terrain as “Mother Nature at her most ruggedly, thornily savage.”

Wheeler’s men had the additional burden of dragging heavy surveying equipment through the dense chaparral.

When at last they reached the top they discovered that the view east was blocked by another peak that rose nearly 200 feet higher than the one they had just climbed.

They immortalized their disappointment by naming the smaller mountain Mt. Disappointment. Then they promptly scrambled up the higher mountain, known today as San Gabriel Peak.

Reidy said he’s not surprised the Disappointment name stuck.

“If you are the federal surveyor and you want to name it Mt. Disappointment, I don’t know who is going to stop you,” he said.

Sadly for Wheeler and his team, their adventures in the San Gabriel Mountains only got worse.

After scaling the San Gabriel Peak, the team summited Mt. Wilson, but on its way down the group’s meteorologist, Douglas Joy, got lost. He was eventually discovered, and rescued, at the bottom of a deep gorge later named Joy’s Ravine.

Joy’s bad luck continued. Later that field season, he died of thirst and exhaustion while attempting to ascend another peak in the range.

Despite completing nine field seasons and cataloging 359,065 square miles of the West, the Wheeler Survey came to an abrupt end in 1879.

Scientists made the case that the mapping of America should not be carried out under the auspices of the War Department. At the same time, the country was suffering from a serious recession. In that milieu, it seemed reasonable to consolidate the four great surveys of the West into one.

In 1879, Congress voted to create the U.S. Geological Survey under the Department of the Interior. Clarence King, one of Wheeler’s competitors, was put in charge of the new agency and Wheeler’s work was sidelined.

Wheeler’s disappointment was so profound he “broke down from defeat” and went on sick leave from 1880 to 1884, according to the late historian Richard Bartlett.

A few years later, in 1889, Wheeler published a seven-volume final report on his life’s work, including 164 maps.

Although Wheeler’s maps never made it into the official canon of the USGS, his teams named hundreds of mountains, valleys, streams and plateaus. Photographers and journalists accompanying the surveyors sent back pictures and vivid tales of a land of geysers, hot springs, mountains and deserts. Farmers, ranchers, miners and scientists relied on the maps created by Wheeler and the other surveyors of the 1870s.

“Not a textbook in geology or any of the natural sciences is published that does not embody the knowledge of the work of the men of the great surveys,” Bartlett wrote.

Today, it takes just a few hours to reach the summit of Mt. Disappointment. The trail is paved and gentle, lined with supersized pine cones and skittish little lizards.

The top of the mountain is flat — a remnant from the 1950s, when Mt. Disappointment became one of 16 Nike missile launch sites in the L.A. area. There also is a cracked helicopter pad and a few humming radio towers.

But if you turn your back to all of that and stand on the edge of the peak, you can look out over the vast Los Angeles basin, hazy and dreamlike behind a thin veil of mist.

Birds dive below your feet.

The mountain range undulates behind you.

There’s nothing disappointing about it at all.