This coronavirus glossary will help you make sense of the pandemic

- Share via

The new coronavirus has thrust a host of unfamiliar terms into our everyday discourse. Some are brand new; others aren’t but are being used in unexpected ways.

Here are some definitions to help you keep up with the latest on the global pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2: The official scientific name of the coronavirus causing the pandemic. It stands for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. It was previously known as 2019-nCoV.

This isn’t the only coronavirus in circulation — four other strains are responsible for 20% to 30% of the common colds we’ve been getting for decades. Two other coronaviruses were responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). The virus that caused SARS was named SARS-CoV, which stands for SARS-associated coronavirus; the virus that caused MERS was named MERS-CoV.

COVID-19: Short for Coronavirus Disease 2019. It’s the official name of the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Incubation period: The time between when someone is infected with a pathogen, such as a virus, and when the first symptoms of illness appear.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

Quarantine: When someone who has been exposed to a disease but is not visibly sick stays away from others for a period of time in case they are infected. By keeping their distance, they can avoid spreading the disease to others. A quarantine usually lasts a little longer than the incubation period for a disease, just to be safe.

A quarantine can be ordered by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or by state and local governments. A CDC-issued quarantine order would look something like this.

Isolation: When someone who is definitely sick stays away from others so that they don’t infect anyone else. In the case of this coronavirus, isolation should continue until the risk of infecting someone else is thought to be low. The decision to end isolation should be made on a case-by-case basis, in consultation with healthcare providers and the local health department, according to the CDC.

Isolation can be ordered by the CDC or by state and local governments. A CDC-issued isolation order would look something like this.

Public health orders: These are legally enforceable directives that may place restrictions on the activities of individuals or groups in the name of protecting the public’s health. Federal, state or local agencies may issue public health orders, such as restricting people’s movements or requiring that their movements be monitored by health authorities.

Containment: A public health strategy in which officials aim to prevent the spread of an infectious disease beyond a small group of people to the broader community.

Containment actions include restricting travel from affected regions, identifying infected people and tracking down everyone they live with or have spent time with (contact tracing), and asking those who have been exposed to the virus to stay at home for a period of time. Although it did not work for COVID-19, containment has been used to keep a measles outbreak from spreading out of control within communities with low immunization, for instance.

Mitigation: The public health goal once a virus has spread so widely that it’s impossible to keep it away. Instead of mainly relying on public health authorities to do things like locate sick people and identify their contacts, health officials ask the public to help slow the spread of the virus. Useful actions can include reminding people to stay home when they’re sick and disinfecting commonly touched surfaces in buildings daily.

One of the main strategies is to practice “social distancing.”

Social distancing: Measures designed to keep people away from crowded places where a virus could more easily spread. In the case of COVID-19, health officials are encouraging members of the public to work from home, cancel mass events and maintain about six feet of space between themselves and others. A radical measure is to close most businesses and order the public to shelter at home except for essential activities, such as purchasing food and caring for relatives, while allowing people to go outside for a walk.

If successful, social distancing measures will help slow the pace of new infections and “flatten the curve.”

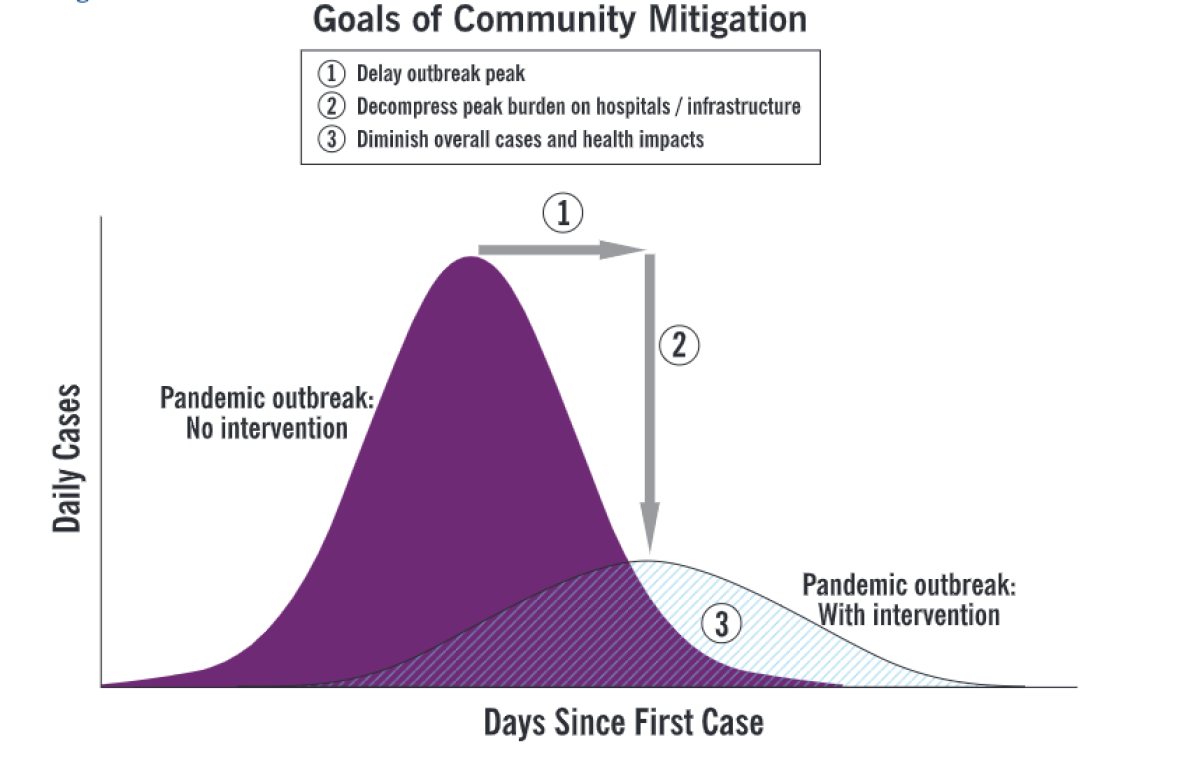

Flattening the curve: This phrase describes the goal of spreading out infections in a population to minimize the number of people who are sick at any given time.

Picture a hump-shaped graph that shows the number of new infections over time. If a disease is spreading quickly, the number of new daily cases of infection will be very high, and the hump will rise steeply. But if the disease spreads slowly, the number of new daily cases will be lower, and the hump will be shorter and wider.

Slowing the spread of the virus can help prevent the hospital system from being overwhelmed by too many patients. If that were to happen, critical care units could run out of the ventilators that are needed to help people breathe if their lungs fail.

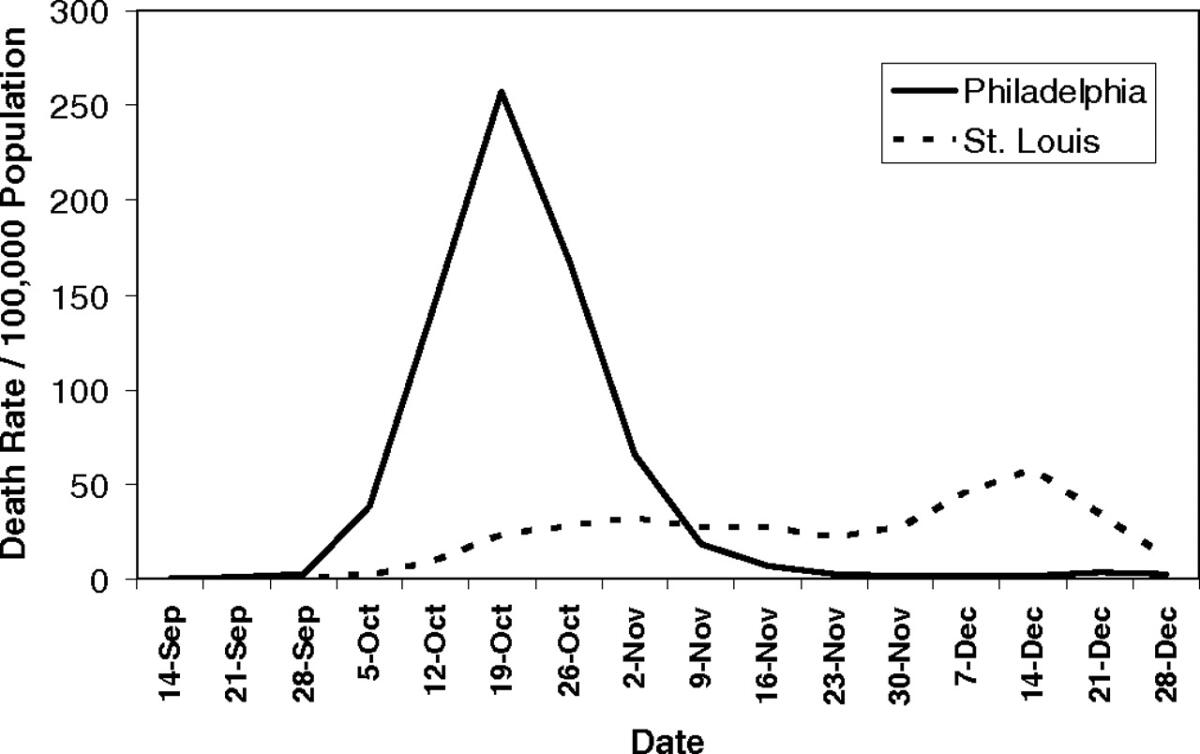

During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, officials in Philadelphia failed to cancel a citywide parade and acted far more slowly to ban public gatherings than their counterparts in St. Louis. As a result, the peak death rate in Philadelphia was much worse than in St. Louis, according to a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published in 2007.

Community spread: When an infectious disease is spreading in an area and the people who are contracting it don’t know where or how they caught it. It’s an indication that a virus is no longer contained to a limited number of people.

Close contact: In the case of COVID-19, it’s anyone who is within 6 feet of a person infected with SARS-CoV-2 for a prolonged period of time.

This includes people who live with, care for or visit an infected person. It can also describe people who merely share a waiting room with an infected patient or who have direct contact with a patient’s infectious secretions (such as by being coughed on).

Outbreak: An increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected among the population in a limited area.

Epidemic: An outbreak that has spread to a wider area.

Pandemic: An epidemic that has spread over multiple countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people.

Presumptive positive: When a public health laboratory has determined a patient has tested positive for a viral infection, but officials are still awaiting confirmation from the CDC. For the purposes of public health, a presumptive positive result is treated as confirmed positive. There are, however, rare situations in which a presumptive positive may turn out to be negative.