Doctors turn to autopsies for clues about COVID-19

- Share via

The COVID-19 pandemic has helped revive the autopsy.

When the coronavirus first arrived in U.S. hospitals, doctors could only guess as to what was causing the strange constellation of symptoms. What could explain why patients were losing their sense of smell and taste, developing skin rashes, struggling to breathe and reporting memory loss, on top of flu-like coughs and aches?

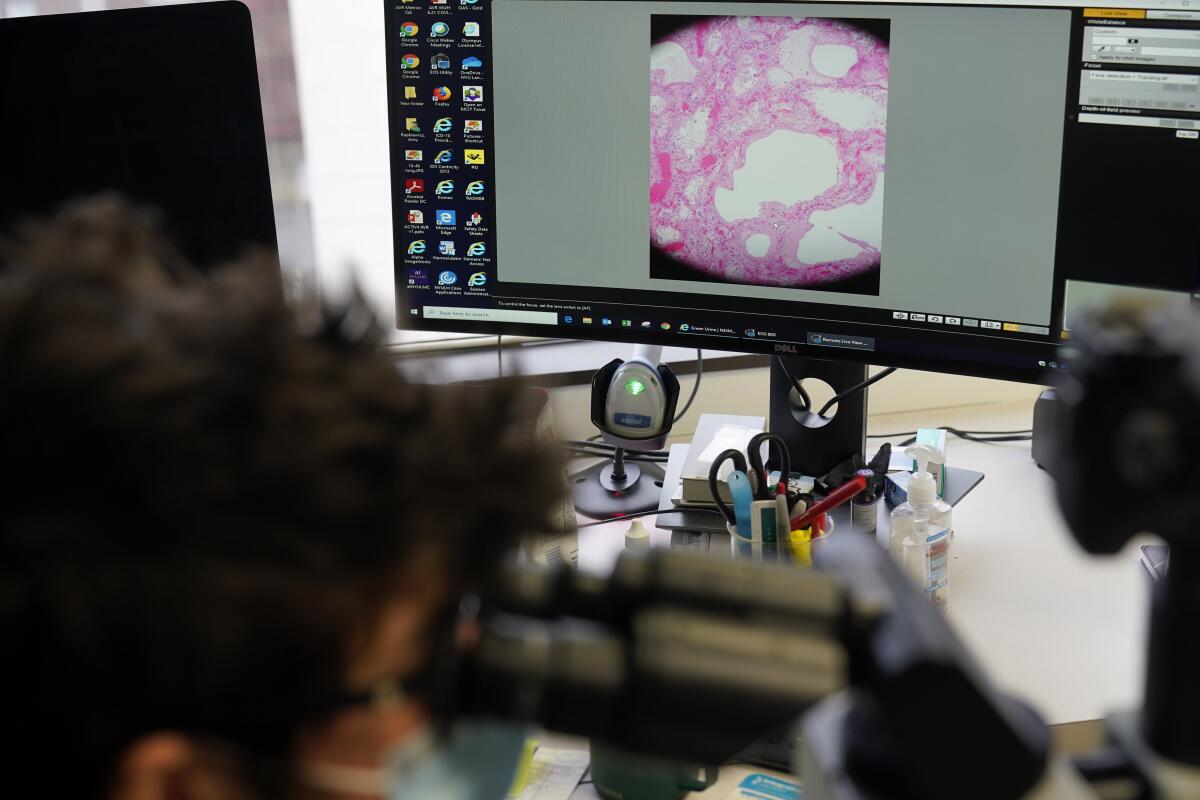

At hospital morgues, pathologists were busily dissecting the disease’s first victims — and finding some answers.

“We were getting emails from clinicians, kind of desperate, asking, ‘What are you seeing?’” said Dr. Amy Rapkiewicz, a pathologist at NYU Langone Health. “Autopsy,” she pointed out, means “to see for yourself.”

“That’s exactly what we had to do,” she said.

Early autopsies confirmed that the coronavirus does not just cause respiratory disease but can also attack other vital organs. They led doctors to try blood thinners in some COVID-19 patients and reconsider how long others should be on ventilators.

“You can’t treat what you don’t know about,” said Dr. Alex Williamson, a pathologist at Northwell Health in New York. “Many lives have been saved by looking closely at someone’s death.”

Autopsies have informed medicine for centuries. They’ve helped improve cancer care, demystified AIDS and anthrax and revealed the extent of the opioid epidemic. Indeed, hospitals were once judged by the number of autopsies they performed.

But autopsies have lost stature over the years as the medical world instead turned to lab tests and imaging scans. In 1950, autopsies were conducted on about half of deceased hospital patients. Today, experts estimate, the rate has shrunk to 5% to 11%.

“It’s really kind of a lost tool,” said Dr. Richard Vander Heide, a pathologist at Louisiana State University.

Some medical centers found it even harder to conduct autopsies this year. Safety concerns about coronavirus transmission forced many hospital administrators to stop or seriously curb the procedures in 2020. The pandemic also led some people to avoid hospitals, causing a general dip in the total number of patients and driving down autopsy rates in some places.

“Overall, our numbers are down, pretty significantly,” from 270 autopsies in recent years to about 200 so far this year, said Dr. Allecia Wilson, director of autopsies and forensic services at Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor.

At the University of Washington in Seattle, Dr. Desiree Marshall couldn’t perform COVID-19 autopsies in her usual suite, because as one of the hospital’s oldest facilities, it lacks the proper ventilation to safely conduct the procedure. Marshall ended up borrowing the county medical examiner’s offices for a few cases early on and has been working since April out of the school’s animal research facilities.

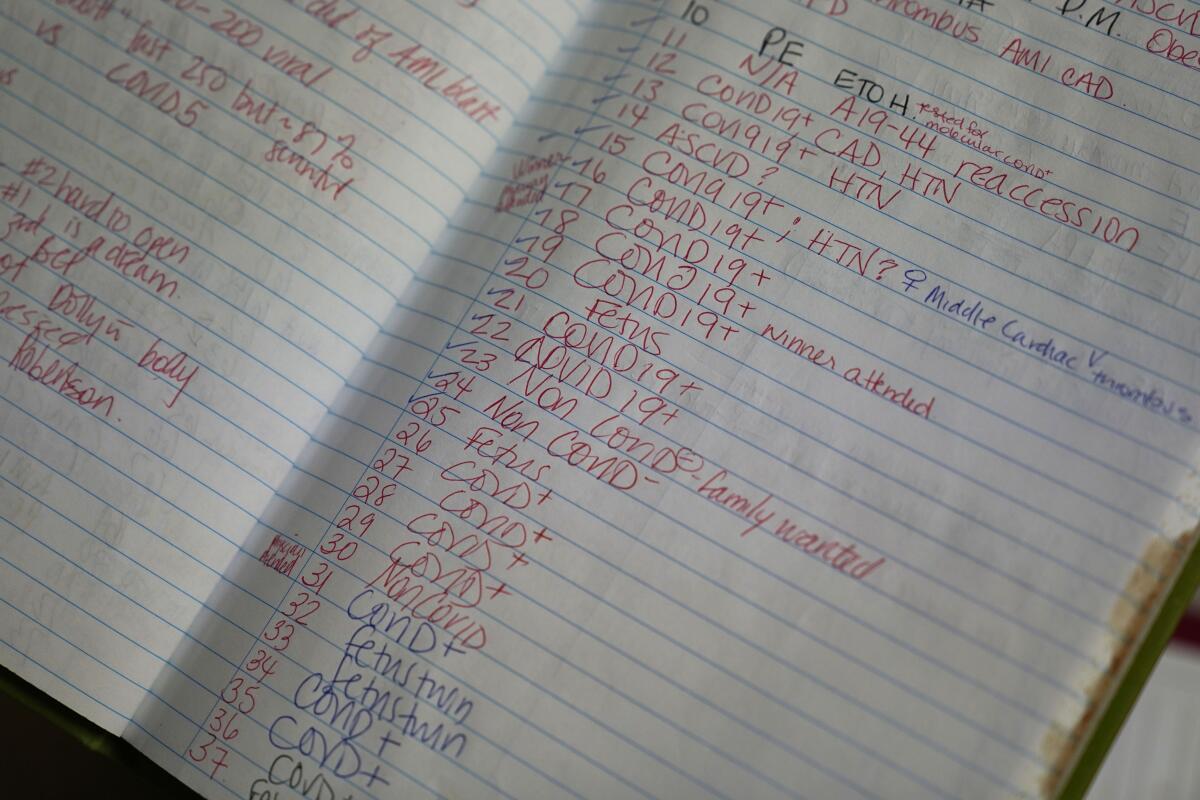

Other hospitals went the opposite way, performing far more autopsies, even under difficult circumstances, to try to better understand the pandemic and keep up with a surge of deaths that has resulted in at least 400,000 excess fatalities in the U.S. this year.

At New Orleans University Medical Center, where Vander Heide works, pathologists have performed about 50% more autopsies than in recent years. Hospitals in California, Alabama, Tennessee, New York and Virginia say they’ll also surpass their usual annual tally.

Their results have shaped our understanding of what COVID-19 does to the body and how we might combat it.

In the spring and early summer, for example, some seriously sick COVID-19 patients were on ventilators for weeks at a time. Later, pathologists discovered that such extended ventilation could cause extensive lung injury, leading doctors to rethink how they use ventilators during the pandemic.

Blood clots that can cause strokes, heart attacks and blockages in the legs and lungs are increasingly being found in COVID-19 patients, including children.

Doctors are now exploring whether blood thinners can prevent microscopic blood clots that were discovered in patients early in the pandemic.

Autopsy studies also indicated that the virus may travel through the blood stream or hitch a ride on infected cells, spreading to and impacting the blood vessels, heart, brain, liver, kidneys and colon. This finding helped explain the wide range of symptoms.

More findings are sure to come: Pathologists have stocked freezers with coronavirus-infected organs and tissues collected during autopsies, which will help researchers study the disease, as well as find possible cures and treatments. Future autopsies will help them understand the disease’s toll on long-haulers, those who suffer symptoms for weeks or months after infection.

Despite making lifesaving discoveries, the ancient medical practice is unlikely to fully rebound after the pandemic because of financial realities and a dwindling workforce.

Hospitals are not required to provide autopsy services, and in those that do perform them, the procedure’s costs are not directly covered by most private insurance or by Medicare.

“When you consider there’s no reimbursement for this, it’s almost an altruistic practice,” said Dr. Billie Fyfe-Kirschner, a Rutgers University pathologist.

Another obstacle: The number of experts who can perform autopsies is critically low. Estimates suggest that the U.S. has only a few hundred forensic pathologists but could use several thousand — and fewer than 1 in 100 graduating medical school students enter the profession each year.

World events influence language, and words once reserved for science or academia — think “social distancing” and “pandemic” — are used all over.

Some in the field hope the 2020 pandemic could boost recruitment — just like the “CSI boom” of the early 2000s, Williamson said.

Wilson is more skeptical, but she can’t imagine her work becoming totally obsolete. Learning from the dead to treat the living is a pillar of medicine, she said.

Autopsies helped doctors understand the mysteries of 1918’s influenza pandemic, just as they’re helping doctors understand the mysteries of COVID-19 more than a century later.

“They were in the same situation,” Vander Heide said of his predecessors from 1918. “The only way to learn what was going on was to open up the body and see.”