AIDS virus used in gene therapy to fix ‘bubble baby’ disease

- Share via

A gene therapy that makes use of an unlikely helper — the AIDS virus — gave a working immune system to 48 babies and toddlers who were born without one, doctors reported Tuesday.

Results show that all but two of the 50 children who were given the experimental therapy in a study now have healthy germ-fighting abilities.

“We’re taking what otherwise would have been a fatal disease” and healing most of these children with a single treatment, said study leader Dr. Donald Kohn of UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital.

“They’re basically ‘free range’ — going to school, doing normal things,” without the worry that any infection could become life-threatening, he said.

The other two children who weren’t helped by the gene therapy later had successful bone marrow transplants. Doctors say it will take longer to know whether any of the 50 are cured, but they seem to be well so far.

An up-close view of how the coronavirus infects cells in the brain and spinal cord helps explain the neurological symptoms of some COVID-19 patients.

The children had severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome, or SCID, which is caused by an inherited genetic flaw that keeps the bone marrow from making healthy versions of the blood cells that form the immune system. Without treatment, it often kills in the first year or two of life.

It became known as “bubble boy disease” because of a case in the 1970s involving a Texas boy who lived for 12 years in a protective plastic bubble to isolate him from germs. It’s now called “bubble baby disease” because roughly 20 different gene defects, including some that affect girls as well as boys, can cause it.

A bone marrow transplant from a genetically matched sibling can cure the disorder, but most kids lack a suitable donor and the treatment is risky — the Texas boy died after one.

Patients now are treated with twice-weekly doses of antibiotics and germ-fighting antibodies, but it’s not a permanent solution.

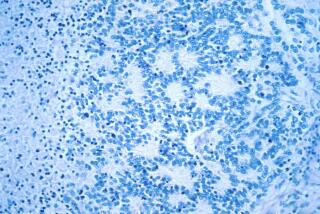

Doctors think gene therapy might be. They remove some of a patient’s blood cells, use a disabled AIDS virus to insert a healthy version of the gene that the kids need, and return the cells through an IV.

Josselyn Kish, now 11 and living in Las Vegas, had it at UCLA when she was 3. As a baby, she suffered rashes, painful shingles and frequent diarrhea, said her mother, Kim Carter.

“Daycare was calling me a couple times a week to come get her because she was always getting fevers.”

After the gene therapy, “she was better right away,” Carter said. Now, “she rarely, rarely gets sick at all” and has been able to recover whenever she has.

That hope extends to Josselyn’s newest infection — she was just diagnosed with COVID-19 and so far has only very mild symptoms.

Black people are the overwhelming victims of sickle cell anemia. An experimental gene therapy being tested on Evie Junior, 27, gives him reason to feel positive.

In all, 27 children were treated at the Los Angeles hospital, three at the U.S. National Institutes of Health near Washington and 20 at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London.

The fact the treatment seems safe across multiple hospitals performing it makes the study “very powerful,” said Dr. Stephen Gottschalk of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis. He had no role in the new study, but he and his colleagues have performed a similar gene therapy on 17 other children with SCID.

“People ask us, is it a cure? Who knows long term, but at least up to three years, these children are doing well,” Gottschalk said. “The immune function seems stable over time so I think it looks very, very encouraging.”

Results of the UCLA-led study were published Tuesday by the New England Journal of Medicine and presented at an online American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy conference.

Grants from U.S. and British government health agencies and the tax-supported California Institute for Regenerative Medicine paid for the work.

Kohn is an inventor of the treatment and an advisor to the company now developing it, London-based Orchard Therapeutics.