A new generation of scientists gets ready to commandeer the James Webb Space Telescope

- Share via

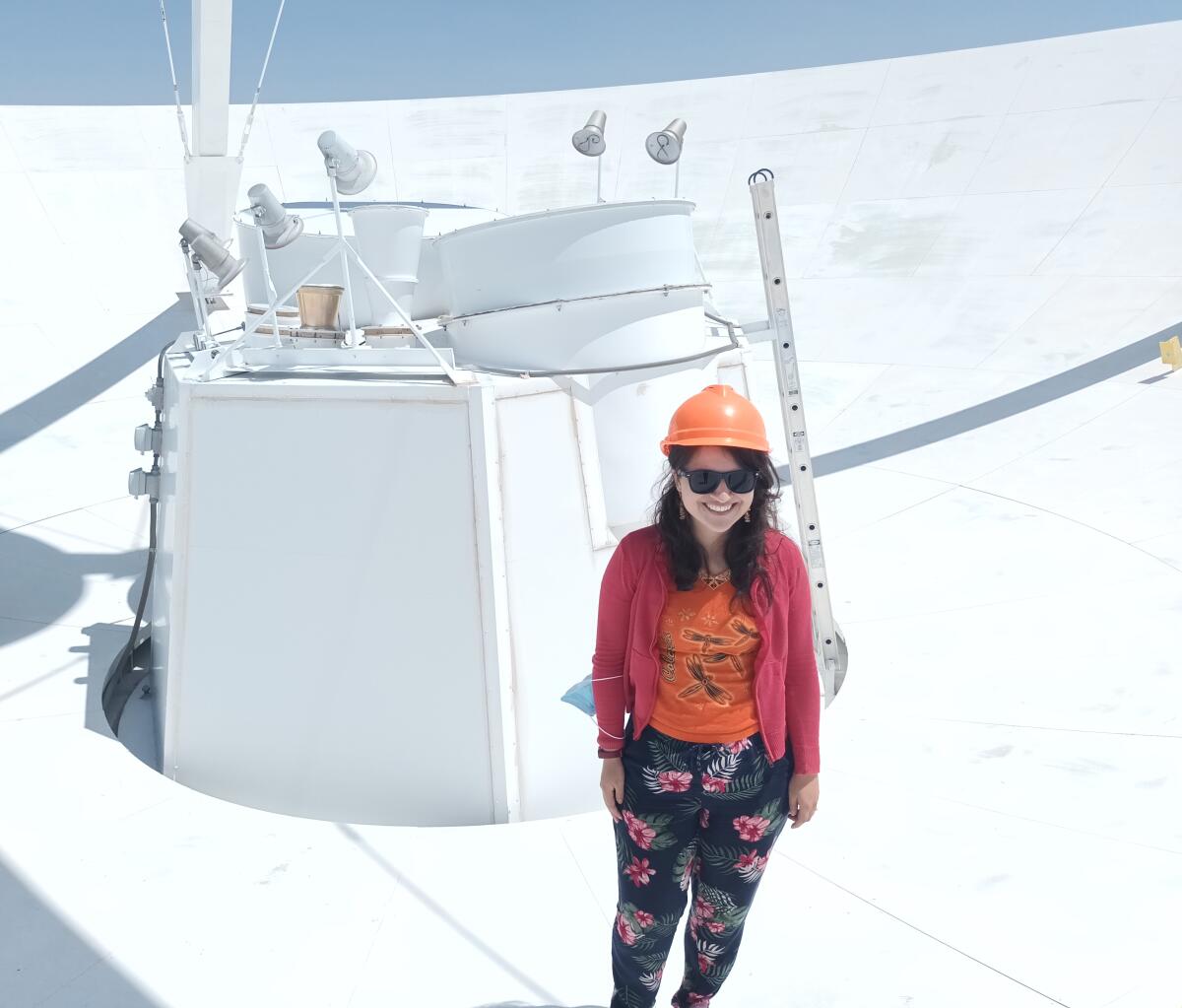

Sofía Rojas was having breakfast with family when the email she’d long anticipated finally landed in her inbox.

It was from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Science Mission Office, informing her that she’s been allotted 18 hours to commandeer the telescope.

“I went nuts,” said Rojas, a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “I was jumping. And my family was not understanding.”

Their bewilderment was understandable. It was March 2021, and Webb hadn’t even launched yet.

But even on the ground, the infrared telescope with an impressive array of gold-plated hexagonal mirrors was something special. The $10-billion instrument was built to collect the faintest light traveling from the earliest stars and galaxies.

Rojas plans to study how primitive galaxies were distributed across the sky and whether mysterious stuff called dark matter helped shape the nascent universe. She and her team will point Webb to randomly selected patches all over the sky and see what they can find.

The first image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope shows innumerable galaxies swirling around a central point, like the light thrown off from a disco ball.

A total of 1,172 observing proposals were submitted to the Space Telescope Science Institute, or STScI, which manages the new telescope. Of those, 286 projects were selected for its first year of operation, including about 25 led by PhD students, according to Christine Chen, an astronomer at STScI.

Six times larger and 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope, Webb’s ability to observe infrared light enables it to see through interstellar dust and detect wavelengths stretched by the expanding universe that are invisible to the human eye.

Rojas was aware these capabilities would make telescope time a hot commodity. To have her proposal accepted “just feels a bit surreal,” she said, “especially because I’m just doing my PhD.”

Rohan Naidu had hoped to use the Webb for his PhD thesis at the Harvard Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. He began his graduate program in 2017 and expected to get access to observing data, “but then there was a major, major delay,” he said.

It wasn’t the first. When NASA selected a prime contractor to build the telescope in 2003, its intended launch date was set for 2010. It was pushed back multiple times before it finally blasted off from French Guiana on Dec. 25, 2021.

That was too late for Naidu’s dissertation, which wound up being about the history of the Milky Way and how it ripped apart and absorbed other galaxies to grow to its current size. But with Webb now open for business, he can revisit his original plan to study how the first galaxies formed a few hundred million years after the big bang. He plans to study a specific part of the sky where galaxies seem to be overabundant.

Webb will tell us “when the first lights in the universe turned on,” he said.

The world gets its first glimpse of ancient light courtesy of NASA’s Webb telescope, the most sophisticated and ambitious deep-space viewing tool yet assembled.

Doing science from space is expensive. To have a proposal accepted, scientists must convince Webb’s keepers that their work cannot be carried out using telescopes on the ground.

UC Berkeley graduate student Aliza Beverage spent several weeks running simulations to show that the observations she wanted to make — of ancient galaxies whose light is too faint to penetrate Earth’s atmosphere — could not be carried out with the telescopes at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the next best alternative.

The same was true for Gourav Khullar, who along with his team spent several sleepless nights writing a successful proposal to use the Webb telescope for all of 20 hours.

Khullar, who recently finished his PhD at the University of Chicago, aims to find the ages of early galaxies by studying what they’re made of. One of Webb’s instruments, the Near-Infrared Spectrograph, splits light to detect imprints of elements that are more abundant in older galaxies.

“There is no other instrument that allows us to spectrally study such early galaxies,” said Khullar, who will continue his work as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pittsburgh.

His target is a galaxy named COOL J1241+2219, which appears to have grown much faster than other galaxies in the young universe.

Beverage, on the other hand, is investigating why some galaxies appear to have fizzled out in those early days.

“Looking back in time over 10 billion years, we see some galaxies that are dead — they’re not forming stars anymore,” she said. “They should be thriving. There’s so much gas around, they could be forming stars, but they’re not. And that’s a big puzzle.”

While observing time has been granted only to select groups of astronomers, access to Webb data is by no means exclusive. A series of early release science projects will help the astronomy community understand the telescope’s observing process and data analysis techniques, and the data they generate will be made available to the public.

Kedar Phadke, a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is involved in one such project. It targets four galaxies, “two of which are very dusty, and two which are not dusty and have already been observed by the Hubble Space Telescope,” he said. Observations of the latter two will be used to calibrate Webb’s performance, while the dusty galaxies will serve as a test for how well its infrared vision can see through dust.

While Webb can see objects that are billions of light-years away, it can only view a tiny part of the sky at a time. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson likened it to observing a grain of sand held at arm’s length.

COSMOS-Web aims to broaden Webb’s vision. Over a period of 208 hours, the project will image a piece of the sky called COSMOS that is three times the size of the full moon.

The results will be released as a catalog for other astronomers, an effort Olivia Cooper, a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, is helping lead. She said she expects Webb’s images of COSMOS will unlock “questions that we don’t already have, which is exciting.”

NASA released the first complete set of images from the James Webb Space Telescope, including stars in their infancy and their final gasps.

Cooper and others have plenty of science to look forward to, and for a long time to come. Webb reached its destination nearly a million miles from Earth with minimal course corrections, saving enough fuel to extend its mission well beyond the 10 years initially hoped for.

Beverage said her advisors are part of a generation of astronomers whose careers blossomed as they racked up discoveries with the Hubble Space Telescope.

“I feel like I’m part of a generation that’s going to be defined by the James Webb Space Telescope,” she said.