Polio was detected in New York. But most people don’t need to worry

- Share via

For the first time in almost a decade, the United States has a diagnosed case of paralytic polio. But prominent public health experts say there’s very little for most people to worry about.

Here’s what happened. Health officials on July 21 identified a polio patient as a person from New York’s Rockland County who was not vaccinated against the disease.

Then on Monday, New York’s Department of Health announced that poliovirus had been detected in wastewater samples taken in June in Rockland County, which is just outside of New York City. About 1 in 200 people who contract poliovirus will present with paralysis as one of their symptoms, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The wastewater findings suggest that other people in Rockland County may have been infected, the CDC told the Associated Press, while adding that no other cases have been found and that there is not enough information to say whether the virus is actively spreading.

The state is urging all unvaccinated residents to get vaccinated for polio.

How did it happen?

Nationally, 92.6% of people receive the full course of polio vaccination by age 2. In Rockland County, that number is 60.5%.

The county experienced a measles outbreak in 2018 and 2019, which sickened more than 300 people. CNN reported at the time that 91% of the cases were in people who weren’t vaccinated or had no record of being vaccinated. The area is home to a large Orthodox Jewish population, which is one of the insular groups that has been targeted by the anti-vaccine movement. Anti-vaccine advocates often raise thoroughly debunked claims that the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine can cause autism. There is no such link.

“The anti-vaccine movement really accelerated during the time of COVID-19,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, the co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital and the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. He published a piece in the scientific journal Nature Reviews Immunology this week outlining how American anti-vaccine activism could threaten global progress on childhood vaccination for other diseases, including polio. He said anti-vaccine activists have turned it into a far-right political movement, which has led to pockets of populations around the country where people are no longer vaccinating their children, which in turn gives diseases like measles and polio an opportunity to gain a foothold.

In 2017, he published an opinion piece in the New York Times with the headline “How the anti-vaxxers are winning.” Today, he says, “I’d say they’ve won. It’s a pyrrhic victory, but they won. They won at great cost to human life.”

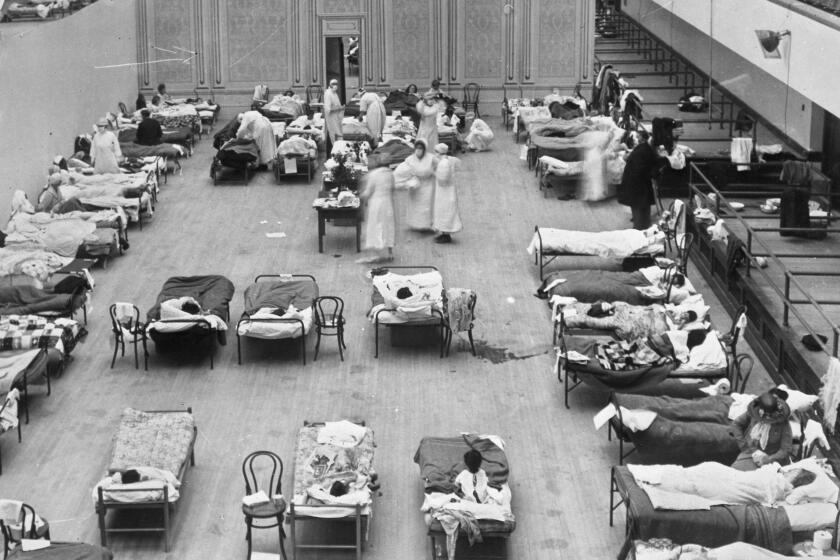

The first major polio outbreak was documented in the U.S. in 1894. The disease reached pandemic levels of spread in the 1940s. Children were particularly susceptible. In 1952, more than 3,000 people died of polio in the United States, and many more were paralyzed. The disease is incredibly contagious and spreads via oral-oral and hand-fecal transmission: sharing a drinking glass, using the same water fountain, eating something prepared by a sick person. Like COVID-19, you can be asymptomatic or have minor symptoms and still be capable of spreading the virus.

After the vaccine was developed, the nation launched a massive vaccination campaign, including a video of Elvis Presley getting vaccinated. Polio was eradicated in the United States in 1979, but it persisted in other parts of the world, including Africa and south Asia. In June, the United Kingdom announced it had detected polio in wastewater for the first time in four decades.

Our species lived through the Spanish flu, polio, ebola, SARS, and swine flu. How have humans gotten themselves out of pandemics in the past? And how might we get out of this one?

What should you do?

“People shouldn’t panic,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Assn. “We’re not looking at a polio outbreak. But when we see these red flags, it just reminds us how important vaccinations are.”

If you are vaccinated against polio, you don’t need to do anything right now. And you probably are: In California, the polio vaccine is required for anyone attending public school or entering childcare. (You can look up your child’s California elementary school’s vaccination rates using this database.) Similar mandates are in place in most school systems and universities nationwide.

If you are not vaccinated, reach out to your doctor and ask about how to get vaccinated. Benjamin said pediatricians’ offices carry the vaccine, since it’s part of the standard immunization schedule for children; your primary care provider should be able to get one for you even if they don’t routinely stock them.

If you have a friend or family member who is not vaccinated for polio, or who has not vaccinated their children for it, you can use some of the strategies outlined in this article to try to persuade them.

You want them to get vaccinated. They don’t. Now what? Tips from experts to have a conversation that could possibly change their mind.

A spokesperson for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health said in an email that anyone who hasn’t yet been vaccinated for polio should be, but noted most adults are already vaccinated.

Like the widely available vaccines for measles, COVID-19 and other diseases, the polio shot is safe and effective.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.