Memes, tweets, snark are the FDA’s new public health weapons

- Share via

When Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed during a National Football League game in January, dozens of Twitter trolls quickly blamed it on COVID-19 shots.

“Snake-oil salesmen” seized on the event, Dr. Robert Califf, commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, said in an interview. The #diedsuddenly hashtag, which appeared in tweets about the incident, is often used to discredit vaccines by linking them to deaths and injuries without evidence.

The FDA is treading a fine line as it attempts to respond to misinformation on social media without amplifying it. After Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter Inc. last year, the platform stopped enforcing a policy designed to suppress false or misleading information about the pandemic.

“Sometimes if you get into a dispute with people that are not telling the truth, it just magnifies the situation,” Califf said. “I think it’s better in this case to reinforce the truth and not get into a back-and-forth argument with people that are peddling falsehoods.”

Since Califf took over a year ago, the FDA has set its sights on social-media disinformation as a public-health scourge. The agency’s efforts started with some savvy responses to pandemic misinformation cropping up on Twitter. Now a crew of agency employees creates memes and other content and feeds them into the internet to defend science.

After Damar Hamlin suffered a cardiac arrest on the football field, speculation arose asking whether COVID-19 vaccines may have played a role. Medical experts say the answer is almost certainly no.

“Historically, the FDA has been able to put out a statement that would be transmitted to doctors, the medical establishment, and then the patients,” Califf said. “We’re now in an era where FDA puts out a statement, and then there’s 24-by-7 alternative information that needs to be dealt with.”

As old as medicine itself, misinformation and unscientific treatments have been supercharged by the immediacy of the internet, and the toll has been significant. Compared with nurses and doctors who are trusted by at least two-thirds of the public, U.S. health agencies enjoy relatively low levels of confidence, according to a 2021 Harvard School of Public Health poll. Just 52% of Americans surveyed said they trust the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s health recommendations; for the FDA it was just 37%.

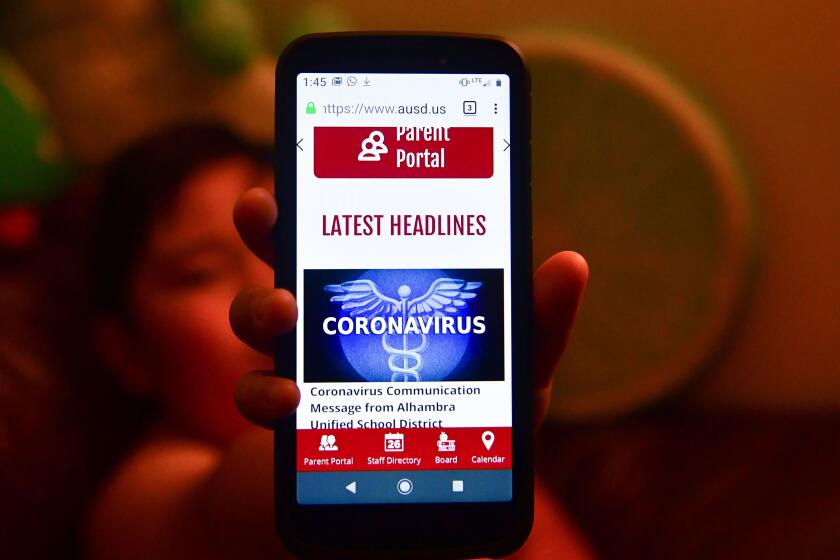

Under pressure to counter unproven pandemic theories — including laboratory leaks and hydroxychloroquine remedies — and stung by allegations that they approved COVID-19 vaccines too fast, the FDA took its fight to social media. Facebook, YouTube and Twitter are increasingly where Americans get their news.

The learning curve was steep. When the agency warned about a TikTok video showing chicken breasts marinated and cooked in Procter & Gamble Co.’s NyQuil cold medication, critics said the FDA only drew more attention to the trend.

“There’s always the risk that when you bring attention to something, people might engage in that,” said Erica Jefferson, the agency’s associate commissioner for external affairs who leads the social-media effort. “But we feel like it’s probably more important, at the end of the day, to point out the risks associated with certain behaviors, and call it out as quickly as possible.”

With so much false information circulating about the coronavirus outbreak, health officials are trying to set the record straight. Here’s why that can backfire.

The expanded effort was inspired by the widespread misuse of ivermectin earlier in the pandemic. Used to eliminate parasites in cattle, the drug was being promoted by some online personalities to prevent and treat COVID-19.

“You are not a horse. You are not a cow,” the agency said on Twitter in August 2021. “Seriously y’all. Stop it.”

That nugget of health advice became the top tweet, in terms of overall engagement, in the history of the FDA’s Twitter account. It has more than 110,000 likes and was retweeted or quoted more than 70,000 times.

The FDA’s early success with Twitter shows the agency can fight fire with fire, said Dr. Dhruv Khullar, assistant professor of health policy and economics at Weill Cornell Medical College.

“I applaud them for recognizing this as an issue and trying to combat it,” he said. “The question of whether it’s effective, I think, is a really open question and a really challenging one.”

Jefferson has expanded the FDA team’s scope to tackle everything from mpox to more general themes like the battle between misinformation and established science. A typical post from the FDA might get far fewer clicks than some misinformation about COVID vaccines, but the agency says it’s a start.

“We need to have more that go viral,” like the ivermectin tweet, Califf said, “but we’ve got to learn how to do that better and better.”