What you need to know to stay safe from COVID now that the public health emergency has ended

- Share via

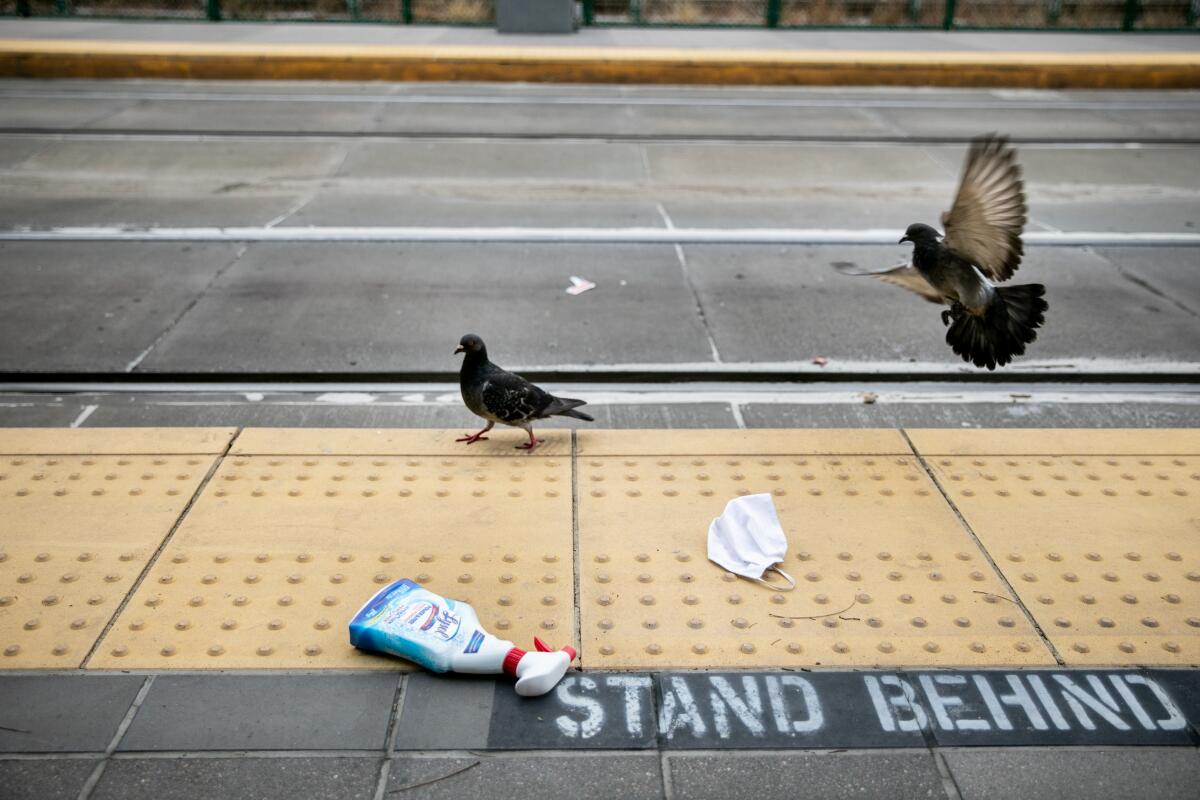

Ready or not, it’s over.

The country’s public health emergency touched off in January 2020 by the sudden appearance of a novel coronavirus formally enters the history books when the day ends Thursday.

It’s not a cause for jubilation, considering that the pandemic has claimed the lives of more than 1.1 million Americans.

Nor should we feel triumphant, since the virus that causes COVID-19 is here to stay. Even in a form tamed by vaccine and tempered by mutation, it still killed 4,719 in the United States over the last month.

And for some time to come, humans will be grappling with the fallout from the social isolation, economic dislocation and political upheaval brought on by a virus that measures 10 nanometers in diameter and spreads through the air with the stealth of a ninja.

Almost every state, territory and tribal entity in the country has declared its health crisis over and rescinded most of the special powers granted to local health departments during the pandemic.

Americans generally seem fine with that. A Gallup Poll released in March found that 49% think the pandemic is “over” in the U.S. — the highest mark since Gallup started tracking that sentiment in the summer of 2021. And roughly three-quarters of those surveyed by KFF that same month said they believe the public health emergency’s end will either have a “positive impact” (27%) or “no impact” (46%) on the country overall.

Not everyone is welcoming Thursday’s milestone. The doctors, scholars and public health advocates who call themselves the People’s CDC say the real Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has abdicated its responsibility to protect the most vulnerable Americans and should be calling for continued masking in public indoor spaces, among other policies. These watchdogs want to see many of the pandemic’s strictures and financial supports remain in place until permanent steps have been taken to fix the racial and ethnic health inequities exposed by the global outbreak.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

Asked when the public health emergency might defensibly end, Dr. Lara Jirmanus, a Boston physician and a spokesperson for the People’s CDC, cited the ongoing threat to the elderly, communities of color and those with compromised immune systems.

“How about when they are as safe as they were before?” she said.

So as we mark the end of an era, a sense of unease has been hard for many to shake. We get it: You have concerns.

After more than 1,200 days of living with and covering the pandemic, we have perspective.

I’m still afraid of dying from COVID-19

You’re not alone. But you are in diminishing company: That March Gallup Poll found that 3% of U.S. respondents remained “very concerned” about coming down with COVID-19, with an additional 22% calling themselves “somewhat concerned.”

Dying of COVID-19 is hardly impossible, but compared with the pandemic’s earliest days, it’s become pretty rare — especially if you’ve not yet reached middle age.

The CDC considers every hospital patient who tests positive for a coronavirus infection a “COVID-19 hospitalization” even though many were admitted for other reasons. As a result, the agency’s numbers suggest an overly grim picture of the country’s health, said Dr. Shira I. Doron, an infectious disease specialist with Tufts Medicine.

“People who say it’s still so terrible — I wish I could take them around the hospital and show them how fine we are,” Doron said. “I wish I could show them how few COVID patients we have, how rare it is for someone to be in for COVID, or to die of COVID.”

Her comments have been echoed by doctors across the country.

“It’s clear the impact has decreased,” said Dr. Jorge Luis Salinas, an infectious disease physician at Stanford. “We have no one with severe COVID at the hospital.”

With the nation’s COVID-19 public health emergency ending and less state cooperation, the CDC has a new plan for monitoring the coronavirus across the U.S.

In the earliest days of the pandemic, studies of outbreaks in China, Italy and the United Kingdom and among passengers of the cruise ship Diamond Princess suggested COVID-19’s “case fatality rate” — which measures deaths among those infected — was somewhere between 0.7% and 1.3%. Later estimates that tried to capture the toll across the world pegged the case fatality rate between 2% and 3%.

But COVID-19 was never an equal-opportunity killer. While fewer than 0.002% of infected children under 10 died of COVID-19, the rate among infected people 80 and over was at least 8%.

Much has changed. The availability of vaccines to prevent severe illness, and of antiviral medications that blunt a new infection, have whittled COVID-19’s ability to kill. Medical professionals who are more experienced at treating the sickest patients have driven the case fatality rate down further. So has the protective effect of immunity gained by vaccines and past infections. The virus’ genetic evolution also appears to have nudged it in a tamer direction.

When everyone around them stops taking pandemic precautions, it gets harder for immunocompromised Americans to protect themselves against COVID.

It’s hard to suss out how each of these factors has affected the likelihood that, if infected, you would die. But a large study published in February suggested that by the time the Omicron variant had spread across the globe, its case fatality rate was 0.239%.

In short, by the time the pandemic’s third year came to a close, the virus that causes COVID-19 had lost roughly two-thirds of its initial killing power, and possibly as much as 92%.

But COVID-19 hasn’t stopped killing people

No, it hasn’t. So let’s look at who continues to be at greatest risk, and what you can do about it.

If you have the good fortune to have lived well into retirement age, then you have the bad luck of being most vulnerable to dying of COVID-19. Since mid-April, virtually all Americans who have succumbed to the disease have been at least 50, and the overwhelming majority have been over 75.

The COVID-19 death rate in the U.S. fell by nearly 50% in 2022, a decline credited to widespread vaccinations as well as a rise in natural immunity.

The nation’s 1.2 million nursing home residents continue to bear the brunt of U.S. deaths. But even there, the situation has improved. According to a nursing home dashboard maintained by the AARP Public Policy Institute and the Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University in Ohio, there were roughly 6 deaths for every 10,000 nursing home residents in the month ending April 26. That’s half the rate of 12 deaths per 10,000 residents seen in the first month of 2023.

You don’t have any say in your age, but you do have a say in your vaccination status. The CDC calculated that in February, adults in the U.S. who received an updated bivalent booster shot were six times less likely to die than people who remained unvaccinated (a group that still represents about one-fifth of the U.S. population). They were also 1.4 times less likely to die than vaccinated people who hadn’t gotten the bivalent booster (and that’s about 80% of the adult population).

So if you’re 65 or older and it’s been at least four months since your last jab, the CDC recommends you go ahead and get another.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended the allowance of an additional updated booster for seniors 65 and older as well as those who are immunocompromised.

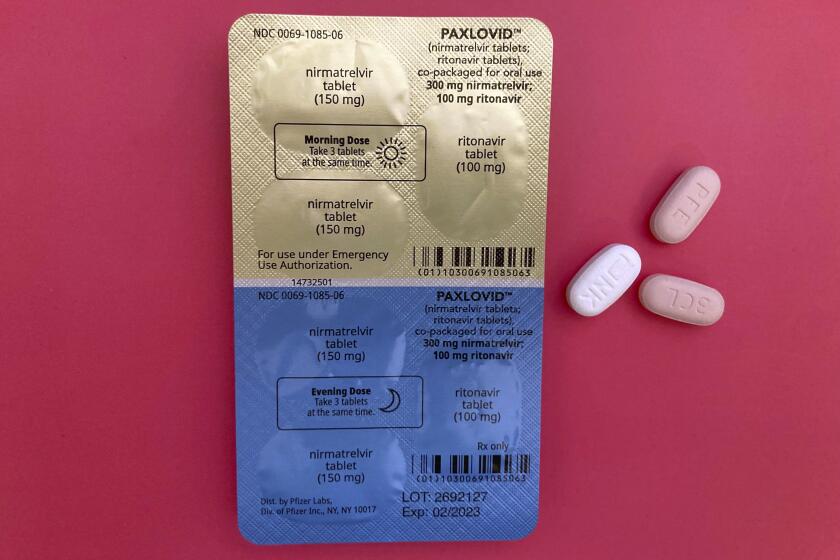

If you are medically fragile or at least 50 years old, you can reduce your chance of dying if infected by taking an antiviral within five days of your first symptoms. Paxlovid reduces the average likelihood of hospitalization or death by about 90%, and molnupiravir reduces it by 31%.

That means you need to remain attentive to how you are feeling and seek out a prescription if you have some combination of the key symptoms of COVID-19 in the Omicron age: sore throat, runny nose, congestion, persistent cough and headache.

I’ve heard that every time I get COVID-19, my chances of dying go up

That’s the apparent takeaway from a study that compared 44,000 U.S. veterans who had suffered multiple coronavirus infections with nearly 444,000 who’d only had one infection and 5.3 million others who’d never tested positive.

Compared with people who’d been infected once, those who had been reinfected were twice as likely to die, three times as likely to be hospitalized, and three times more likely to experience heart problems or blood clotting over the following six months.

Deciding how many Americans we are willing to let die of COVID-19 each year is necessary to put the pandemic behind us.

That sounds scary, but experts caution that veterans cared for in Veterans Affairs hospitals hardly represent an average population. Ninety percent of them were men, and only 12% were younger than 39. The study didn’t account for which coronavirus variant caused each infection. And both infected and reinfected people were identified by the VA’s COVID-19 testing system, meaning any infected vet who was doing fine went uncounted by researchers.

There’s another problem with the findings: They don’t make immunological sense, said Doron of Tufts Medicine.

“Subsequent infections are less severe,” she said. In healthy people, the immune system’s first look at the virus (either the real thing or a synthetic version from a vaccine) prompts a complex and multilayered defensive response. Even after antibodies — among the first lines of defense — begin to fade, T cells can fight back against a reinfection, making it milder and often shorter than the previous bout.

In order to move through a world where the coronavirus is endemic, we need a reliable way to assess our individual level of immunity. Here’s how we can.

Still, as the authors of the study put it, “reinfection is not benign; it is best to avoid it.”

If you’re still reading, odds are you already believe that. But you should also know that, given the Omicron variant’s prodigious transmissibility, reinfection will be nearly impossible to prevent.

That may not be a bad thing. Virologists have long predicted that over time, virtually all of us will build up the kind of immunity we have to other coronaviruses that cause the common cold.

I’m worried that my mask won’t protect me if no one else is wearing one

Few issues have been more contentious than the value of face coverings. First, health authorities advised, we didn’t need them (because medical professionals needed them more). Then we did (because they appeared capable of reducing viral spread). Now we’re told they’re not even necessary in hospitals? What gives?

Today, the CDC says that given the nation’s high levels of vaccine- and infection-induced immunity and the availability of effective prevention tools and treatments, universal masking is unnecessary in most public settings, including healthcare settings. In schools, the CDC recommends that “children should wear a mask if they need extra protection from COVID-19.”

That may come as a surprise, but the fact is “we just have too much data at the population level that masking doesn’t change the course of the pandemic,” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at UC San Francisco.

An exhaustive review of studies that tested the protective value of masks against the coronavirus as well as several strains of flu left researchers “uncertain whether wearing masks or N95/P2 respirators helps to slow the spread of respiratory viruses.”

Even in healthcare settings, where infection was widespread, there was limited evidence that universal masking offered much value given the current status of the outbreak. And an influential group of doctors whose job is to stem the spread of diseases in hospitals recently called for an end to universal masking in healthcare settings.

During the Omicron era, rules requiring mask use in U.K. hospitals didn’t prevent COVID-19 spread when there were no other pandemic precautions in place, a new study finds.

Those doctors made clear that under different circumstances, universal masking “was a critical protective measure.” In future pandemics or significant localized outbreaks, the practice could be justified again, they wrote. But “when the expected benefits of such policies are low,” they added, it’s a policy “whose time has come and gone ... for now.”

Then they said out loud what many have thought but kept to themselves: that “masking impedes communication,” that face coverings “obscure facial expression” and make listening harder, that they “contribute to feelings of isolation; and negatively impact human connection, trust, and perception of empathy.”

I don’t want to go to public spaces or socialize with others for fear of catching COVID-19

Again, you’re not alone. In late March, 23% of Americans told pollsters they had avoided large crowds to protect themselves over the last week. In addition, 18% had stayed away from planes, buses, subways or trains, and 14% had avoided going to public places. One in 10 had shunned even small gatherings.

But consider this: Your social life matters to your health — a lot. People who are socially isolated are more likely to suffer a stroke or heart attack, not to mention depression, cognitive impairment and an earlier death. Social isolation makes normal — and fixable — impairments like hearing loss less evident. And unchecked health problems become bigger and sometimes different problems. Hearing loss is a risk factor for dementia.

These are trade-offs you really should consider before giving up on your book club or your mah-jongg group, or discouraging your friends and family from dropping in.

I’m afraid of getting long COVID

Sufferers of long COVID, or post-acute sequelae of COVID, are a large and mystifying group.

Lingering problems with heart, kidney and lung function are common among people who were hospitalized with severe COVID-19. But not all long COVID sufferers were very ill. Even people with mild or asymptomatic infections have experienced problems for months afterwards, ranging from brain fog and exhaustion to heart palpitations, depression and an inability to exercise.

Since June 2022, the CDC and the U.S. Census Bureau have been conducting the Household Pulse Survey to gauge Americans’ experiences during the pandemic. So far, the survey has found that 28.4% of all adults with a confirmed coronavirus infection suffered lingering symptoms lasting three months or more.

A new study offers insight into the prevalence of long COVID and suggests who might be more likely to develop the condition.

But there’s growing evidence that most cases of long COVID resolve themselves after a few months, and that new cases of long COVID are becoming less common. In the most recent Household Pulse Survey, only 11.2% of U.S. adults said they were currently experiencing long COVID symptoms.

That long COVID is more unusual in the Omicron era is suggested by a study published in March. In a group of 1,201 healthcare workers from nine Swiss healthcare networks, those who’d been infected with the original version of the coronavirus were 67% more likely to report symptoms of long COVID than those who were not infected. However, healthcare workers who were infected with the Omicron variant were no more likely to report long COVID symptoms than those who’d never been infected.

It’s not clear whether these nurses and doctors were protected by COVID-19 vaccines or by Omicron’s gentler ways. But Dr. Carol Strahm, an infectious disease doctor who co-wrote the study, leans heavily toward the latter explanation. As long as the Omicron variant dominates, he said, “our results should provide reassurance” that people are now unlikely to develop long COVID.

Stanford’s Salinas noted that mysterious and prolonged symptoms after a viral infection “have always existed.” Only because the pandemic virus infected so many people in so short a time has the phenomenon come under close scrutiny.

The prospect of suffering “post-infective syndrome” after a bout of flu or a cold sore doesn’t send people into a protective bubble, he added. At this point in the pandemic, neither should fear of long COVID, he said.

“I recognize that people are suffering from long COVID and that it’s very real,” Salinas said. “But at a personal level I don’t navigate the world or conduct my life based on fear of long COVID.”

I’m afraid tests, vaccine and treatments for COVID-19 will become really expensive

This is one of those end-of-pandemic problems that will unfold over time, but which should be largely manageable for now.

The end of the public health emergency means that the cost of testing for coronavirus infections will shift for many Americans. At-home tests will be available in drugstores, but at $12 to $15 apiece, they’ll be an expensive first step for people worried about their symptoms. The more reliable and time-consuming PCR tests will be subject to insurers’ rules and copays.

For people with health insurance, vaccine boosters and antiviral medications will remain available, though they may come with a copay.

A pandemic allows the Food and Drug Administration to authorize vaccines and drugs for emergency use, even after the health emergency ends.

In April, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced a $1.1-billion “bridge program” designed to preserve access to COVID-19 vaccines and medications for uninsured Americans. Whether it’s a “bridge” to anywhere lasting remains to be seen: The Biden administration has sought to create a “Vaccines for Adults” to plug current holes in vaccine access for uninsured adults, but it’s bogged down in budgetary scuffles.

In the interim, the bridge program will ensure COVID-19 care at commercial pharmacies and federally funded health centers that serve low-income communities, and through local public health organizations.

The same program will also hold some drug manufacturers to their public commitments to provide vaccines and treatments free of charge for the uninsured.