Q&A: How this Stanford freshman brought down the president of the university

- Share via

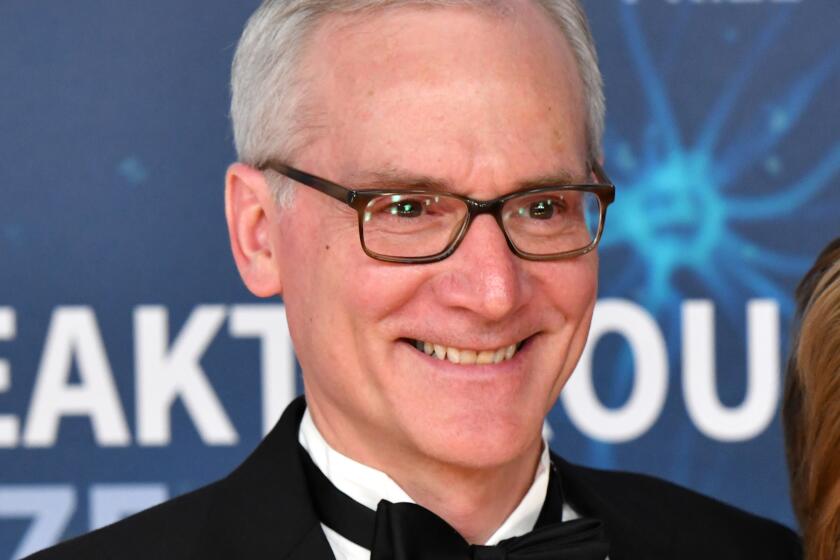

Rumors of altered images in some of the research papers published by Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne had circulated since 2015. But the allegations involving the neuroscientist got little attention beyond the niche scientific forum where they first appeared — until Stanford freshman Theo Baker decided to take a closer look.

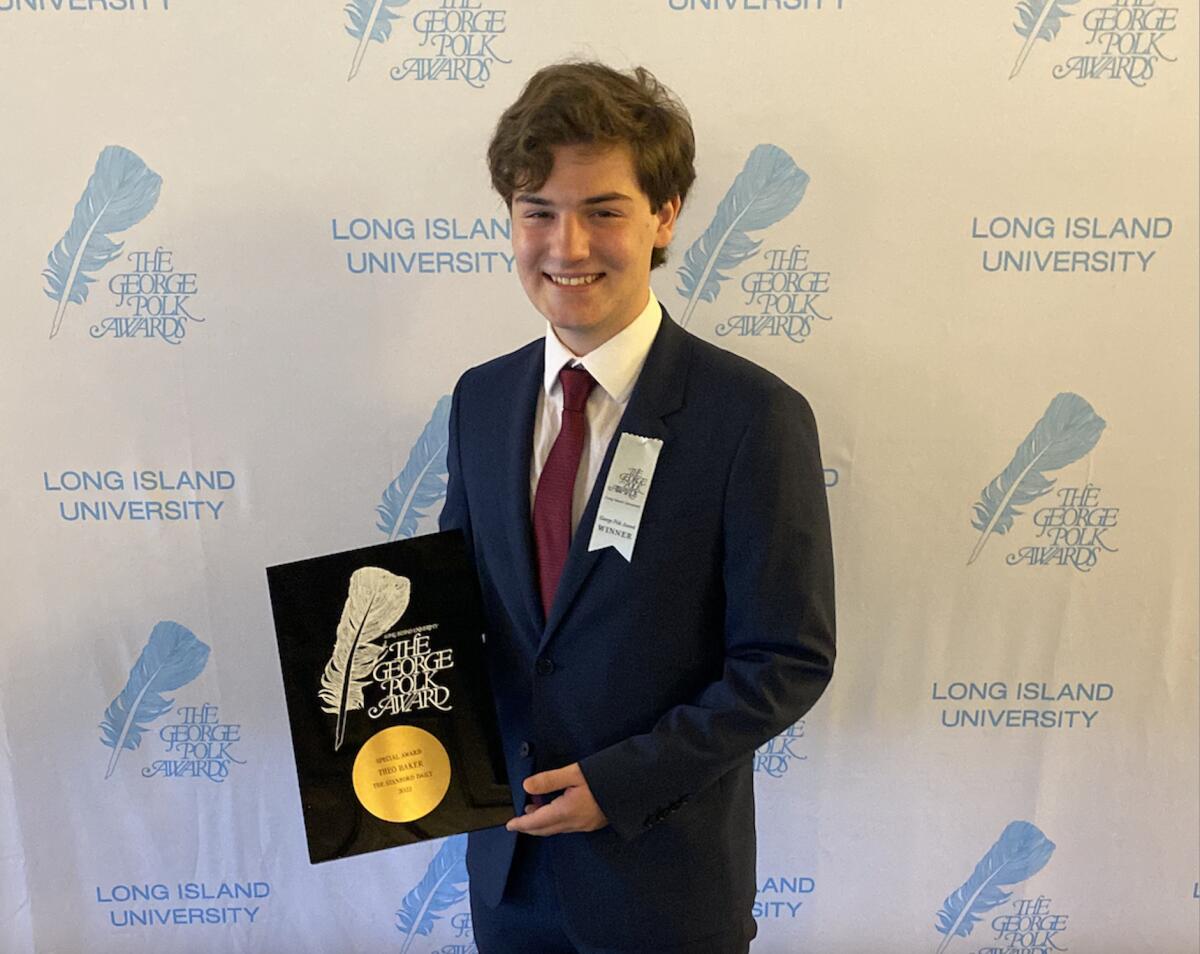

Baker, a journalist for the Stanford Daily, published his first story on problems surrounding Tessier-Lavigne’s research in November. His dogged reporting kicked off a chain of events that culminated this week with the president’s announcement that he would step down from his post at the end of August.

Tessier-Lavigne acted Wednesday after an expert scientific panel convened by the university determined that he failed on multiple occasions to correct errors in his published research on Alzheimer’s disease and related topics, and that he managed labs that at times produced sloppy or even manipulated data.

Of course, Baker covered that too.

After a review of allegations found flaws in his scientific articles, Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne said he will resign.

In February, the 18-year-old from the Washington, D.C., area became the youngest-ever recipient of journalism’s prestigious George Polk Award for his work on the investigation. Journalism runs in the family: Baker is the son of the New York Times’ chief White House correspondent, Peter Baker, and New Yorker columnist Susan B. Glasser.

The Los Angeles Times caught up with him to discuss his reporting and its consequences.

How did this story come to your attention?

There’s a pretty highly technical scientific forum called PubPeer where people analyze published works. People there suspected that certain images in things that Tessier-Lavigne had published over the years looked like they’d been Photoshopped.

I decided, well, if this is true, this is really interesting. I’m going to take this to an actual forensic image analyst who can take a look and say if there has been manipulation or Photoshopping.

Are you referring to Elisabeth Bik?

Yes. Elisabeth Bik is the foremost research misconduct investigator of this type in the entire world. She is eagle-eyed, she is professional, and she — unlike a lot of her colleagues — was willing to speak on the record from the start.

I talked to a number of image analysts and all of them had basically the same analysis as Elisabeth, but they would only be on background [meaning they were not willing to have their names published]. Elisabeth is a fearless champion of research integrity, and she was willing to work with us from the start. I am very grateful to her for that.

What pressures did you experience as a student journalist reporting on your own institution?

It’s a nerve-racking thing. We’re really lucky that the Stanford Daily is celebrating its 50th year of independence from the university. That was really important. This reporting I don’t think could have happened without that. Especially after we began receiving legal threats from Tessier-Lavigne, I certainly think the fact that we are independent made it possible for us to keep digging.

What kind of legal threats did you receive?

Stephen Neal, the chair emeritus of Cooley, one of the biggest law firms in the Silicon Valley area, represented Marc Tessier-Lavigne and sent a number of aggressive letters requesting retractions or seeking to block the publication of articles that detailed Tessier-Lavigne’s involvement in alleged incidents of fraud. Neal is also a former attorney for [disgraced former Theranos CEO] Elizabeth Holmes.

What was your reaction when the university commissioned an independent investigation into the issues your reporting raised?

It was not independent at first. They announced an investigation that was going to be led by a special committee of the Board of Trustees. Very quickly, that became another story for us to report on. I discovered that one member of the committee [fund manager Felix Baker] had an $18-million investment in Tessier-Lavigne’s biotechnology company — and this is a person who had been appointed to investigate Tessier-Lavigne.

After that, he stepped away and they hired the lawyer who then hired some other scientists.

That panel confirmed several problems you raised but said it could not verify the allegation that Tessier-Lavigne’s former employer Genentech found evidence of fraud in a 2009 paper.

This 2009 paper in Nature was huge, once thought to be Nobel-worthy. It proposed a totally new cause for the neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s patients.

The panel agrees that the paper was wrong and should be retracted or corrected substantially, which is something that even a few months ago Tessier-Lavigne was saying was an utterly inappropriate response. They found that it was riddled with substandard scientific practices. What they did not find was evidence of fabrication.

Scientific papers co-authored by Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne are being reviewed following concerns that images they contain may have been altered.

That’s where our reporting goes a little bit further. We published a story in February which detailed the accounts of four very high-level executives and senior scientists at Genentech, recounting how there was an internal review in 2011 that ordered more research into the underlying experiments after finding out that they were having trouble replicating them.

After attempts to reproduce the research failed, the program was canceled and the postdoc [who did the experiments] left the company. These four senior executives concluded that it was because the underlying experiments had been fabricated. A fifth executive later told us the same thing.

After the report came out, you published a story that said several key witnesses refused to speak to the panel because they were not guaranteed anonymity.

Yes. Not only are these sources talking about a very powerful man, they’re also bound by nondisclosure agreements with Genentech. With these lack of guarantees of anonymity, there was an unwillingness to speak to the committee.

What was it like to balance reporting this story with your academic work?

I’ve been taking the maximum number of units because I am a moron. [laughs] I came to Stanford because I wanted to milk it for every opportunity that it had and I wasn’t going to let one story stop me from doing that.

I spent well over 1,000 hours on sourcing this investigation, and that has obviously taken a huge chunk of time away from things. And yet, I still have been able to do cyber policy research, election disinformation research. I’ve been able to take history and philosophy and computer science classes. I’m really trying to make sure that I maximize Stanford because I know just how lucky I am to be there.

This is all in your first year at college?

Yes. I was 17 when the first articles came out.

How are you spending your summer?

I can’t go into too much detail, but I’m in Europe reporting future investigations.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.