Remembering Angels pitcher Nick Adenhart, 10 years after his death

- Share via

The path wasn’t clear, but the destination was not in doubt. Nick Adenhart seemed bound for baseball greatness, with lightning in an arm that produced 94-mph fastballs and sharp overhand curves, before the 22-year-old Angels pitcher was killed by a drunk driver on April 9, 2009.

The only question was how he’d get there.

Joe Saunders, a former Angels pitcher whose clubhouse locker was next to Adenhart’s, thinks Nick would have been a solid starter for five or six years before moving to the bullpen — like Hall-of-Famer John Smoltz — and becoming a dominant setup man or closer.

Former Angels reliever Kevin Jepsen, who came up through the minor leagues with Adenhart and was also a 2009 locker mate, is convinced Nick had the stuff and mental makeup to flourish as a big league starter for a decade or more.

“I know baseball is not everything in the big picture of life, but Nick was such a good talent, he had such unbelievable potential, that you think, were there All Star Games, was there a Cy Young Award, in his future?” said Jepsen, who retired in 2018.

“You sit there and start thinking, what kind of career would Nick have had in baseball? And I’m sure it would have been a great one.”

Tuesday marks the 10th anniversary of one of the darkest days in franchise history. Adenhart, just hours after pitching six scoreless innings against the Oakland Athletics in his fourth major league start, was killed when the car in which he was riding was broadsided by a minivan a few miles north of Angel Stadium shortly after midnight.

Adenhart, the small-town kid from Williamsport, Md., who overcame major elbow surgery in high school, was the organization’s top pitching prospect, a lean-and-lanky 6-foot-3, 185-pound right-hander.

Adenhart and three friends were headed to a dance club in Fullerton to celebrate his 2009 debut when their Mitsubishi Eclipse was struck by a Toyota Sienna that blew through a red light at 65 mph at the intersection of Orangethorpe Avenue and Lemon Street.

The driver of the Eclipse, Courtney Stewart, 20, a Cal State Fullerton student and aspiring broadcast journalist, and another passenger, Henry Pearson, 25, a law school student and aspiring sports agent, also were killed.

A fourth passenger, former Cal State Fullerton catcher Jon Wilhite, survived despite suffering an internal decapitation — the impact of the crash separated his spine from his skull — an injury that is often fatal.

It took years for Wilhite, who also suffered collapsed lungs, broken ribs, a fractured scapula and brain shearing, to recover. Now 34, Wilhite was married in Temecula last fall and remains close to the Angels, serving as a guest instructor in spring training in recent years.

“He’s a walking miracle,” said Tim Mead, the Angels vice president of communications. “Jon is doing so well.”

The driver of the minivan, 22-year-old Andrew Thomas Gallo of San Gabriel, had a blood-alcohol content of more than twice the legal limit more than two hours after the crash. He was driving on a suspended license because of a 2006 drunk-driving conviction.

Gallo was convicted of three second-degree murder charges and sentenced to 51 years to life in prison. Currently an inmate at the Ironwood State Prison in Blythe, Gallo will be eligible for his first parole hearing in 2028.

“I took three lives when I was 22 and seriously injured another,” Gallo, now 32, said in a written response to questions sent to him in prison. “I took Nick Adenhart, Courtney Stewart and Henry Pearson’s lives and severely impacted Jonathan Wilhite’s life in many ways. I not only took their lives, but I also destroyed all those who loved and cared for them.

“They were all so young, lives cut short through my irresponsible actions. I took life for granted and never weighed the consequences for my selfish, reckless ways. They had so much to live for, so much of a great future ahead of them. That’s something I have to live with.”

::

Injuries to John Lackey, Ervin Santana and Kelvim Escobar opened spots in the Angels rotation at the start of 2009, and Adenhart seized one with a strong spring. Scheduled to pitch the team’s third game, he urged his father, Jim Adenhart, to fly from Maryland to California for the game, “because something special is going to happen,” agent Scott Boras recalled at the time.

Jim Adenhart was among the crowd of 43,283 who saw Nick dominate the Athletics, striking out five. Adenhart left with a 3-0 lead that was coughed up by the bullpen and the Angels lost, 6-4.

“I was the last guy to leave the clubhouse, and he was icing his shoulder,” former Angels center fielder Torii Hunter said of Adenhart. “I told him, ‘Congrats, it’s the first one of many, enjoy this small victory and have a good time with your friends and family tonight.’

“We were excited for him one night, and the next morning he’s gone. I can’t believe it’s been 10 years, man, 10 years since I got that call at 7:15 a.m. I will never forget that phone call.”

Neither will Bobby Wilson, the former Angels catcher and a close friend of Adenhart who was at his Salt Lake City rental home with triple-A teammates when Adenhart’s mother, Janet Gigeous, delivered the devastating news.

“We were just sitting there on the couch staring at each other, like, there’s no way this happened,” said Wilson, who opened this season with Detroit’s triple-A team at Toledo. “It still feels like there’s no way it could have happened.”

The April 9 series finale against the A’s was canceled. A makeshift memorial, filled with flowers, balloons, stuffed animals and heartfelt messages from fans, sprung up around the mound outside the stadium’s main entrance. It remained all season, lovingly maintained by longtime ticket office manager Susan Weiss.

The Angels opened their clubhouse at 7 a.m. so Jim Adenhart could spend time at Nick’s locker. Then-clubhouse manager Ken Higdon handed Jim the jersey Nick had worn the night before.

Later that afternoon, Jim Adenhart met several players and coaches in the clubhouse and thanked them for befriending his son. Bench coach Ron Roenicke led the group in a prayer.

Jim Adenhart, wearing a red Angels pullover, was escorted to the stadium pitcher’s mound, where he lingered for a few minutes. He crouched, appearing to cry. He stood up and looked toward the heavens for a few moments, bidding farewell to his son.

::

It took days for the initial shock of the accident to wear off.

“The day it happened, it doesn’t really hit you,” said Saunders, who retired in 2015. “It didn’t really sink in for me until a few days later when I’m sitting at my locker, looking to my right, at his locker, and I’m like, ‘Nick’s not coming again. Nick’s not coming again. Nick’s not coming again.’ That’s when it really sinks in.”

There were so many emotions — shock, anger, denial, profound sadness — as the full team reunited Friday, April 10, the day after the accident. As they tried to process their grief, another daunting challenge hit the Angels through their hugs and tears:

They had 159 games to play.

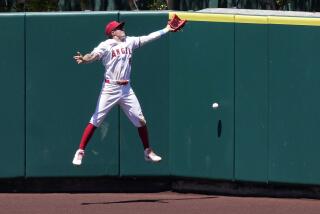

Black patches with Adenhart’s name and No. 34 were sewn over the hearts of jerseys. A mural of Adenhart in mid-delivery was affixed to the center-field wall. Decisions were made to keep Adenhart’s locker intact and to set up lockers for him on the road. Adenhart’s jersey was hung in the dugout for every game.

The Angels, heavy favorites to win the American League West that season, were still in a fog, losing nine of 14 games after Adenhart’s death.

They fell to 6-11 and 5½ games back April 25, a two-week stretch in which several players and club officials attended funeral services for Adenhart in Maryland. A private memorial service in Angel Stadium on April 23 seemed to bring some closure.

Then the Angels rallied. A 10-3 run pushed them above .500. A 17-6 run in June and July and an eight-game win streak in mid-July vaulted them into first place.

An offense powered by Vladimir Guerrero, Kendrys Morales, Juan Rivera, Bobby Abreu, Mike Napoli, Hunter, Erick Aybar and Chone Figgins supported a rotation led by Lackey and Jered Weaver, and the Angels won the division by 10 games.

After clinching their fifth AL West title in six years with an 11-0 win over Texas on Sept. 28, players doused Adenhart’s jersey with beer and Champagne and went en masse to the mural on the wall, bowing their heads and tapping Adenhart’s face.

“We weren’t only playing for Nick, we were playing for his dad, playing for his family,” Saunders said. “We as a team kind of thought that if we could win games, his family would maybe smile. Nick would smile looking down on us.”

Manager Mike Scioscia played a huge role in guiding the Angels from tragedy to triumph. His mantra after Adenhart’s death remained the same.

“It’s not about our pain, it’s about their pain,” Scioscia said repeatedly throughout the 97-65 season, alluding to Adenhart’s parents. “They lost a child. That is beyond my comprehension.”

The Angels swept the Boston Red Sox in the AL division series before losing to the New York Yankees in a six-game AL championship series, falling two wins short of the World Series.

“We’re always motivated as baseball players to win, but that extra added push was definitely for Nick Adenhart,” Hunter said. “Of course, God had different plans. It didn’t work out for us, and we fell short, but at the same time, I think all of us got closer through Nick Adenhart.”

::

The Angels don’t plan to formally acknowledge the anniversary of Adenhart’s death before Tuesday night’s game against the Milwaukee Brewers, but the pitcher’s legacy lives on.

Adenhart remains part of the team’s pregame video montage, set to the music of Train’s “Calling All Angels.” Though his No. 34 jersey is not officially retired, no Angels player has worn it since Adenhart.

A Little League field in Hagerstown, Md., is named after Adenhart. Weaver, who carved Adenhart’s initials into the back of the mound before every start until his retirement after 2017, named his son, born in 2013, Aden.

“What I remember most about Nick was how awesome of a guy he was,” Jepsen said. “He was fun and very funny. He loved to mess around. He was a guy people gravitated toward, and he did it without trying. It was just a part of who he was.”

About 200 miles east of Anaheim, in a desert town near the California-Arizona border, the man responsible for the deaths of Adenhart, Pearson and Stewart says he is trying to make a living amends.

Gallo has not reached out to family members of the victims “out of respect” for them, and no family members have contacted him.

“There is so much I would like to say, so much that needs to be said,” Gallo said. “I can only imagine what the grieving process has been like.”

Gallo said he is trying to “turn my life around” by taking college classes, becoming an active member of Alcoholics Anonymous, getting involved in the prison Christian Ministry and facilitating inmate-peer education programs that help youths struggling with drug-and-alcohol problems.

It will be years, perhaps decades, before he is released, but he has plans for life after prison.

“I would like to give back to the community and become a positive member of society through sharing my story and the effects that drugs and alcohol and irresponsible choices can have on someone’s life,” Gallo said. “I want to have a positive impact on people’s lives.”

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.