With a Castro as an ally, MLB focuses on the high-stakes smuggling of Cuban ballplayers

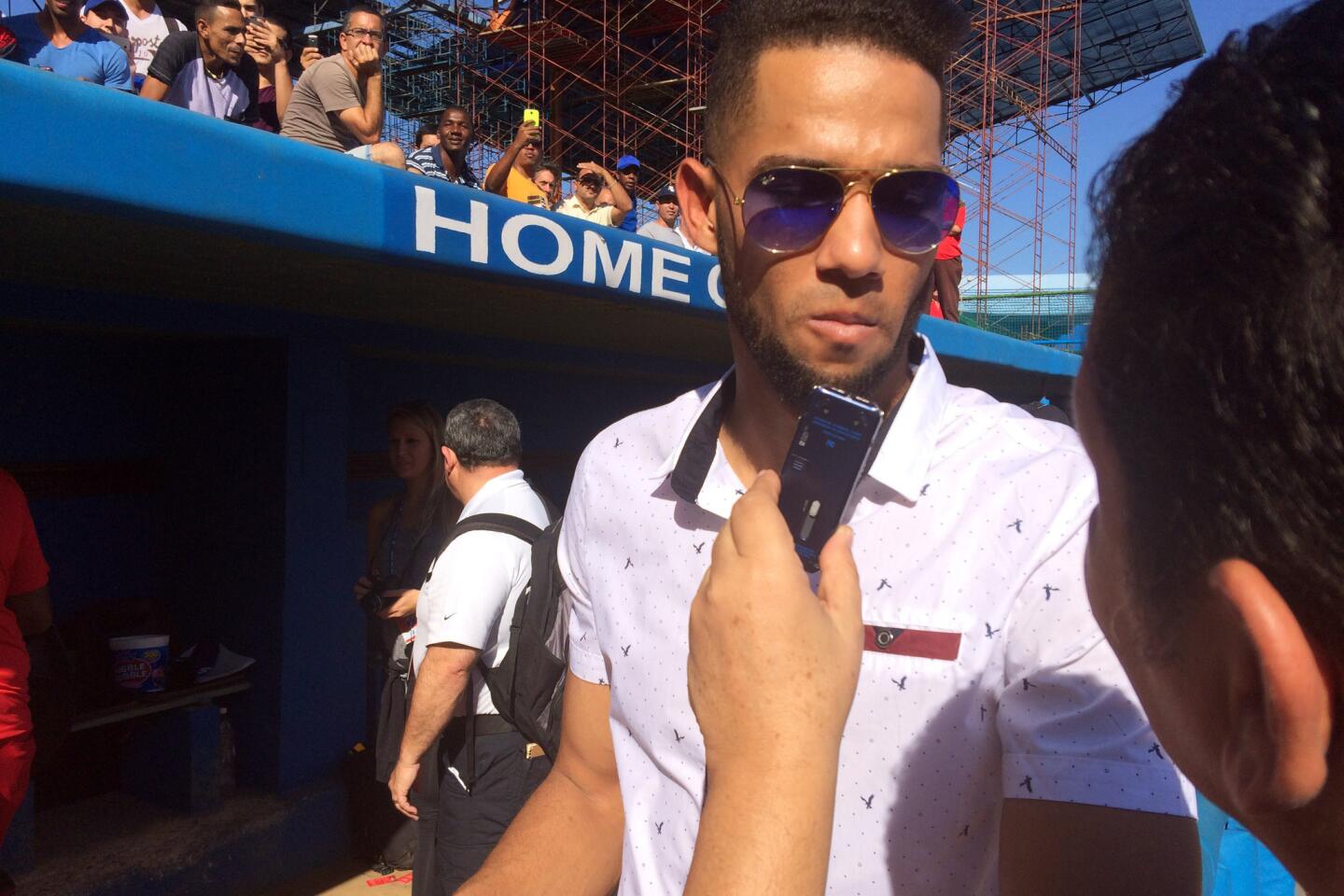

Dodgers outfielder Yasiel Puig holds his nephew during a clinic at Esadio Latinamericano in Havana during a MLB goodwill tour in Cuba.

- Share via

Reporting From Havana — The story of Yasiel Puig’s escape from Cuba reads like a crime thriller, complete with speedboats, kidnappings, betrayal, drug kingpens and murder.

So like most baseball fans, Dan Halem was appalled the first time he heard it.

But unlike most fans, Halem, as Major League Baseball’s chief legal officer, had the power to do something about it.

“The trafficking issue has been very eye-opening,” he said. “It’s not transparent to us. And it’s very troubling to our owners and our commissioner.

“That’s why we’re very focused on fixing this issue. It really is our top priority.”

It won’t be an easy fix. Yet the will to address the problem may open an avenue toward repairing three generations of bitterness and mistrust between Cuba and the U.S. And perhaps even more significantly, Halem now has a willing ally in Antonio Castro, son of former Cuban President Fidel Castro and vice president of the Cuban baseball federation, who last week welcomed a high-level MLB delegation to the island for a historic three-day goodwill tour.

Relations between the two countries have been frozen in a Cold War stance for nearly 60 years before beginning to thaw last December, when President Obama and his Cuban counterpart, Raul Castro, announced steps toward normalizing ties.

As a result, embassies have reopened in Havana and Washington, talks to resolve nearly $2 billion worth of competing property claims have started and bilateral negotiations have begun on a range of other issues, from civil aviation and drug interdiction to telecommunications and human rights.

Hardliners on both sides have threatened to erase all that — which is where baseball comes in. Even on the chilliest days of the Cold War, baseball was a passion Americans and Cubans shared with equal fervor. So if ongoing talks to stage spring training games in Cuba and to legalize the movement of players between the countries are successful, it could have ramifications that reach far beyond the ballfield.

“We found a common thread,” said former Dodger manager Joe Torre, who was part of last week’s mission. “Baseball is like a religion. It’s the universal language.

There are a lot of things that need to be worked out. But this is a good start.

— Joe Torre, Major League Baseball executive and former Dodgers manager

“There are a lot of things that need to be worked out. But this is a good start.”

Actually the seeds for change, as far as MLB is concerned, may have been planted a decade ago when federal prosecutors — angered by the deaths of a young Cuban boy, two Cuban grandmothers and three others — began cracking down on the lucrative operations that had smuggled people 90 miles across the Straits of Florida for years.

Authorities needed a high-profile case to mark the change so it went after Chatsworth sports agent Gustavo “Gus” Dominguez, who had represented dozens of defectors, including the first, pitcher Rene Arocha, who walked away from the Cuban national team in a Miami airport in 1991.

The decision to prosecute Dominguez may have been a calculated one because he was well-respected and had largely avoided the unethical and illegal practices that defined many of the agents who worked with Cuban players. When Dominguez was sentenced to five years in prison, it sent a shiver through South Florida’s tight-knit Cuban baseball community.

It didn’t stop the human trafficking, though. Instead, smugglers chose a new route, using high-performance speed boats to navigate the longer journey from western Cuba to Mexico. The trip was not only twice as long but it was far more dangerous and expensive as well.

Plus the location, southern Mexico, drew in drug cartels, who demanded payment to allow Cuban players to travel through their territory.

As the bolsa negra — or black market trade — in Cuban ballplayers grew, middlemen emerged to act as liaisons between the smugglers and prospective agents. Soon rival gangs were stealing players from one another at gunpoint, and those suspected of betrayal wound up dead.

Smuggling operations that once cost as little as $7,000 to get someone from Cuba to Key West were now costing a quarter-million dollars or more.

In the case of Puig, court records say the outfielder paid four men $1.3 million after signing a six-year, $42-million contract with the Dodgers in 2012. Another man, Yandris Leon Placia, the so-called captain of the smuggling operation, would up dead, shot 13 times.

But the only thing that makes Puig’s story unique are some of the details. After Leonys Martin was smuggled from Cuba to Mexico in 2010, he was held at gunpoint in Mexico and his family was confined to a house in Florida in an effort to extort more money from the player, now an outfielder with the Seattle Mariners.

Both the Puig and Martin cases would up in court, offering a detailed look at the dangers Cuban players endured to get to the U.S. And that proved an embarrassment for Major League Baseball.

But as long as Cuba refused to let its players leave for the U.S. and as long as U.S. law prevented MLB from dealing directly with Cuban nationals, the smuggling would continue — making even greater tragedies inevitable.

“No matter what your viewpoint, I think everybody in both countries agrees that human trafficking is really bad and having baseball players — [or] any Cubans — having to risk their lives or put themselves in danger is not a good situation. It’s very troubling to our owners and our commissioner,” said Halem, who opened detailed talks with Castro last summer, about eight months after President Obama and Raul Castro announced their own tentative steps toward détente.

For the Cubans, the main impetus for cleaning up the process may be financial. More than 300 players have followed Arocha off the island since 1991 and in the last 3 1/2 years, just five played signed contracts worth a combined $287 million.

Former Cuban pitching great Pedro Luis Lazo takes part at a baseball camp in Cuba during the MLB goodwill tour.

Cuba got nothing for developing those players. And with defectors facing a possible prison term for returning to the island, little of that money figures to be spent in Cuba either. That’s a problem for the cash-strapped government, which has begun allowing players to sign with teams in Mexico and Japan in exchange for 20% of their earnings plus income tax.

Cuba stands to make far more allowing players to go to the big leagues. And if it were to include a clause requiring some to participate in Cuba’s domestic winter league as well, it would address complaints of local fans, who have been critical of a declining level of play caused by the spate of defections.

During last week’s MLB tour, Antonio Castro attempted to demonstrate his goodwill by welcoming four Cuban players back to the island, where they joined four other major leaguers in giving clinics for young players, something both sides hailed as a good first step.

“We’re experiencing a new relationship with Major League Baseball, one where we want the baseball players to play baseball and where we live in a normal world and they have the same rights,” Castro said during Thursday’s clinic in Matanzas, where U.S. and Cuban flags flew side-by-side atop the stadium’s scoreboard.

Added Halem: “We’re going to have to have a discussion and ultimately determine whether a system that’s agreeable to the Cuban baseball federation is also acceptable to the owners and the players.”

Both sides must step softly though — Castro because his plan would undo measures his baseball-loving father put in place in the early 1960s and Halem because a truly open relationship with Cuba would require lifting the U.S. economic embargo — something congressional Republicans have vowed to block.

In the meantime, baseball officials from both countries say they will continue to build on the foundation cemented last week. And if they succeed, it just may set open an avenue for the politicians to follow.

“It’s not just a baseball concern. It’s a people concern,” said former All-Star Tony Clark, now executive director of the players association. “There are so many moving pieces and so many groups and interests that are a part of that conversation that it’s hard to say what that end point will be other than providing everyone a safe opportunity to realize their dreams.

“I’d love to be — in 10, 15, 20 years from now — having a conversation [and] suggesting that in 2015, in December, we had a goodwill tour that really seemed to set the stage for all the great things that have happened between now and then.”

Follow Kevin Baxter on Twitter: @kbaxter11

ALSO IN THE NEWS

Trump once fought an ugly battle over an L.A. landmark -- and blinked

First off-leash dog park comes to Beverly Hills

‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’ now holds record for largest opening weekend ever

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.