Frank Robinson, Hall of Famer and first African American big-league manager, dies at 83

- Share via

Hall of Fame outfielder Frank Robinson, the only major leaguer to be named most valuable player in both the National and American leagues and the first African American to manage in the big leagues, died Thursday in Los Angeles after a long illness, according to Major League Baseball. He was 83.

Robinson rose from the sandlots of Oakland to become one of baseball’s most feared sluggers — his 586 home runs rank 10th on baseball’s all-time list.

“Frank Robinson’s resume in our game is without parallel, a trailblazer in every sense, whose impact spanned generations,” Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. “He was one of the greatest players in the history of our game, but that was just the beginning of a multifaceted baseball career.”

Robinson, who was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1982, spent more than 60 years in baseball, 21 as a big league player from 1956 to 1976, 16 as a manager for four franchises, and more than a dozen in a variety of executive roles, most recently as a special advisor to Manfred and honorary president of the American League.

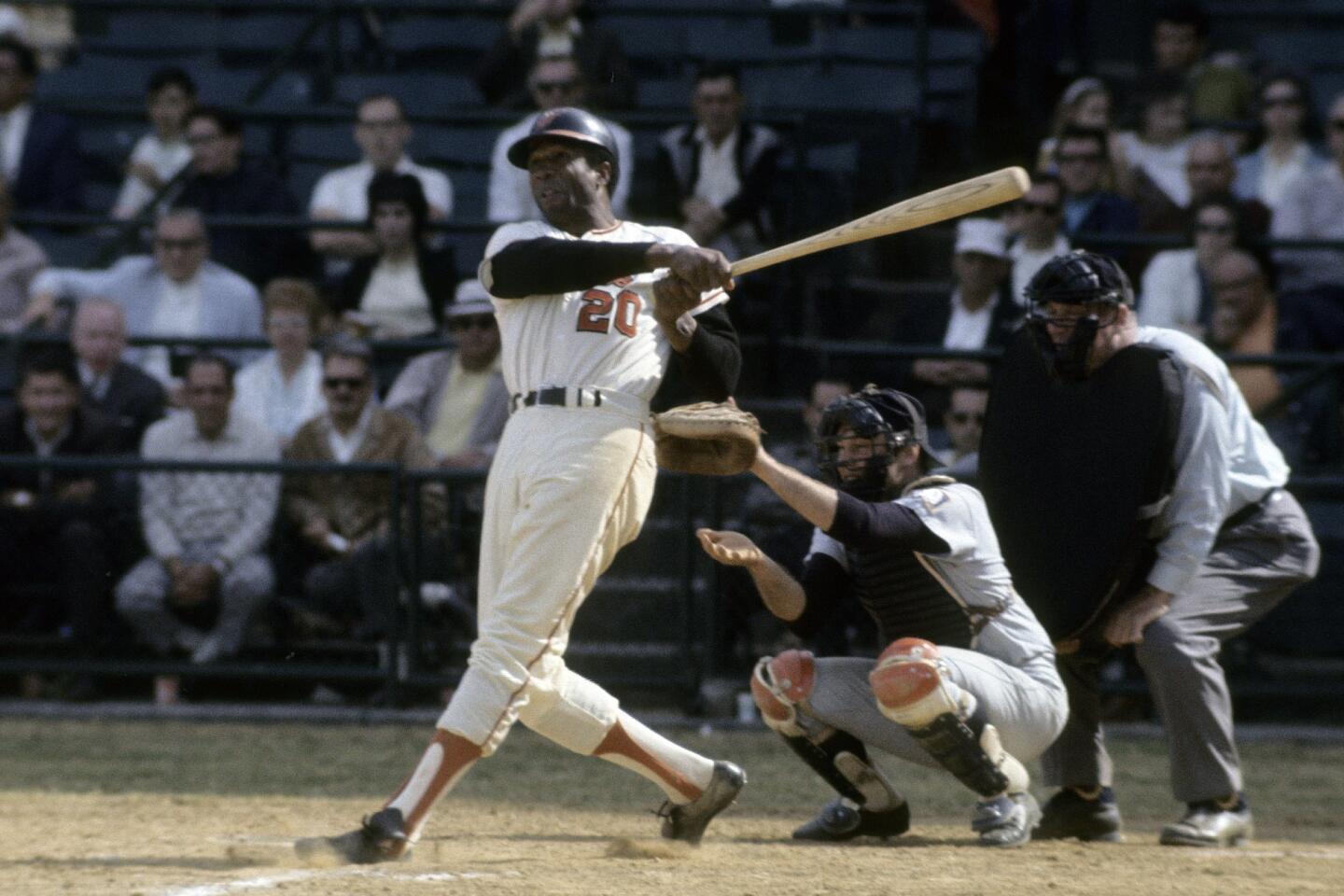

He left his most indelible mark as a player, a wiry strong, 6-foot-1, 184-pound power hitter who had a .294 career batting average, a .389 on-base percentage, a .537 slugging percentage and was a 12-time All-Star.

“I don’t rank guys, but I’d put him right there with the best ever,” the late Earl Weaver, manager in Baltimore when Robinson played for the Orioles, said in 2011. “And he’d be a lot higher in those ranks if not for some of the artificial home runs that came out of those bats.”

When Robinson retired as a player after spending three of his final seasons with the Dodgers (1972) and Angels (1973-’74), he ranked fourth on baseball’s all-time home run list, behind Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth and Willie Mays. He has since been passed by six others, including the Angels’ Albert Pujols. Three of those players — Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez and Sammy Sosa — have been linked to performance-enhancing drugs.

“Frank Robinson and I were more than baseball buddies — we were friends,” Aaron, 85 and a longtime rival, said Thursday in a statement. “Frank was a hard-nosed baseball player who did things on the field that people said could never be done. I’m so glad I had the chance to know him all of those years. Baseball will miss a tremendous human being.”

Robinson was one of the game’s most ferocious competitors, first in Cincinnati, where in 10 seasons he won National League rookie of the year (1956) and MVP (1961) honors, then in Baltimore, where he led the Orioles to World Series titles in 1966 and 1970.

He won American League MVP and Triple Crown honors in 1966, leading the league in average (.316), homers (49) and runs batted in (122). He won World Series MVP honors that October, hitting two homers in the Orioles’ four-game sweep of the Dodgers.

Robinson was a force in the batter’s box, hitting for average and power, and in the dugout and clubhouse, leading by example and infusing his teams with grit.

He expected nothing less than maximum effort and intensity, from himself and his teammates, and he backed down from no one, especially opposing pitchers, all but daring them to knock him down by crowding the plate.

“He hated all pitchers with a passion,” said Elrod Hendricks, a former Orioles teammate who died in 2005. “They were trying to take money out of his pocket and food out of his family’s mouths.”

The late Gene Mauch was said to have fined his pitchers when he managed the Philadelphia Phillies for throwing at Robinson because such tactics only served to motivate him. Still, Robinson was hit by pitches 198 times in his career, leading the league in that category seven times.

“Pitchers did me a favor when they knocked me down,” Robinson told Baseball Digest in 2006. “It made me more determined. I wouldn’t let that pitcher get me out.”

Born Aug. 31, 1935, in Beaumont, Texas, Robinson was the youngest of 10 children in what was essentially a single-parent household. Robinson’s father deserted the family when he was an infant, and his mother, Ruth, struggled to provide her children with the basic necessities.

When Robinson was 4, his mother moved the family to West Oakland, and it was on the playgrounds near his home on lower Myrtle Street that Robinson’s hard-nosed approach to the game was formed. Even playing pickup games as a youngster, he would slide hard into second base to break up double plays.

“That’s the way baseball is supposed to be played,” Robinson said during his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1982.

The only problem, noted Robinson, who starred at Oakland’s McClymonds High, was that he would rip his pants and scrape his left leg repeatedly.

“That field,” Robinson explained, “was covered by asphalt.”

Whether it was the racial taunts and death threats he endured as a young player — Robinson was arrested in 1961 after he waved a gun threateningly in a dispute with a restaurant employee in Cincinnati — or a comment by former Reds general manager Bill DeWitt, who called him “an old 30” when Robinson was traded to Baltimore in 1966, Robinson seemed to play with a chip on his shoulder.

“I don’t think it was a chip; it’s just that he was so intense,” Weaver said. “Frank never gave up an at-bat. I don’t care if we were losing 10-0 or winning 10-0, each time he walked to plate, it was him against that pitcher, and he wanted to win the battle every time.

“The way he slid into second to break up double plays … that could be construed as a chip. But that’s the way the game should be played. You play as hard as possible and don’t give up anything.”

Robinson slid so hard into former Chicago White Sox second baseman Al Weis in 1967 that he was knocked unconscious when his head hit Weis’ knee. Weis suffered a broken leg on the play.

“Frank Robinson,” wrote former Times columnist Jim Murray, “always went into second like a guy jumping through a skylight with a drawn Luger.”

Pride and competitiveness were among Robinson’s trademarks as a player, but they may have been detrimental to his managerial career, which began when the Cleveland Indians made him Major League Baseball’s first African American manager in 1975.

His tactical skills weren’t the issue in Cleveland, where Robinson served as player-manager for two seasons before being fired in 1977, or in San Francisco, where he managed the Giants from 1981 to 1984.

“Robinson had problems dealing with anyone less talented and less intense, which was just about everyone,” former Times national baseball writer Ross Newhan wrote in 1989.

“He acknowledged that when it came to managing a clubhouse of players of varying ability, potential and motivation, he often resorted to intimidation and manipulation. He would yell and attempt to embarrass.”

Robinson, speaking to the Akron Beacon Journal in 1995, admitted: “It was hard for me to let things go, with either a player or the umpires. With the Indians, I took too many things personally. If I thought someone crossed me, I held it against them for a long time. Criticism would just stick to me.”

Robinson led the Giants to winning seasons in 1981, and in 1982, San Francisco came within two games of the NL West title.

But the Giants slipped to 79-83 in 1983, and they were 42-64 in 1984 when Robinson, curt with the press, short of patience with some younger players and critical of the front office, was fired.

“After I was fired for the second time as manager, I think I finally got a different perspective on myself,” Robinson told The Times in 1989. “After I looked at myself and the way I’d lived, maybe I was wrong more than I was right. Maybe it’s not the way you look at yourself, but the way other people see you.”

Robinson brought a new attitude back to Baltimore when he took over as manager six games into a 1988 season in which the Orioles lost a record 21 games to open the season and finished 54-107.

The 1989 Orioles, with an array of rookies and castoffs from other clubs, held first place for most of the season before losing the division in the next-to-last game. Robinson was named AL manager of the year.

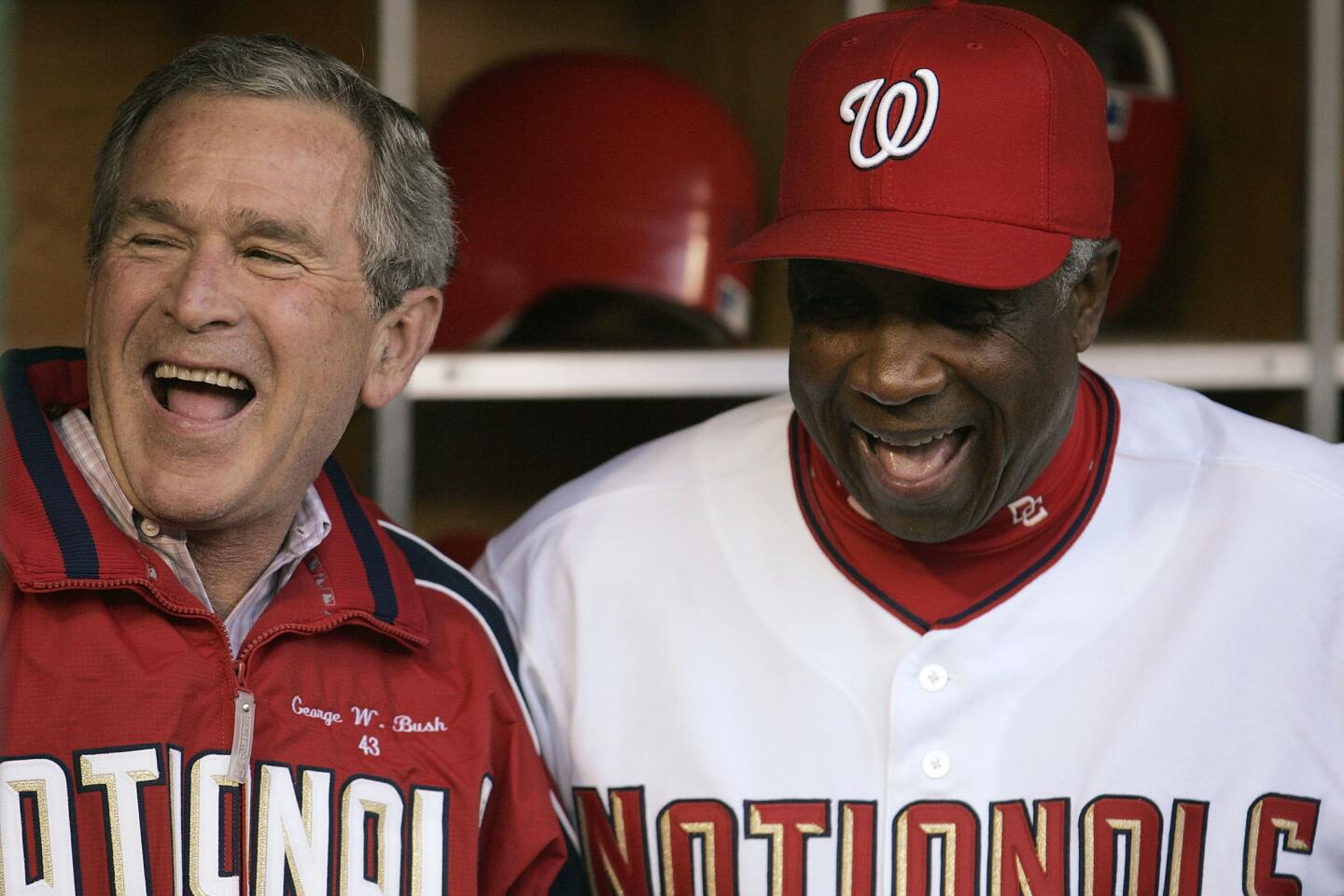

Robinson was replaced during the 1991 season in Baltimore by Johnny Oates. He spent his final five years as a manager with the Montreal Expos (2002-2004) and Washington Nationals (2005-2006), finishing with a 1,065-1,176 overall record as a manager. Robinson worked briefly as an ESPN analyst and then joined Major League Baseball’s front office, working as an advisor. In 2005, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush.

“Frank Robinson was someone I looked up to as a man and as a ballplayer and tried to emulate,” Tony Clark, executive director of the players union, said Thursday. “His skill and ferocity on the field were matched by his dignity and sense of fair play off the diamond. … The fraternity of players and the baseball family have lost a giant.”

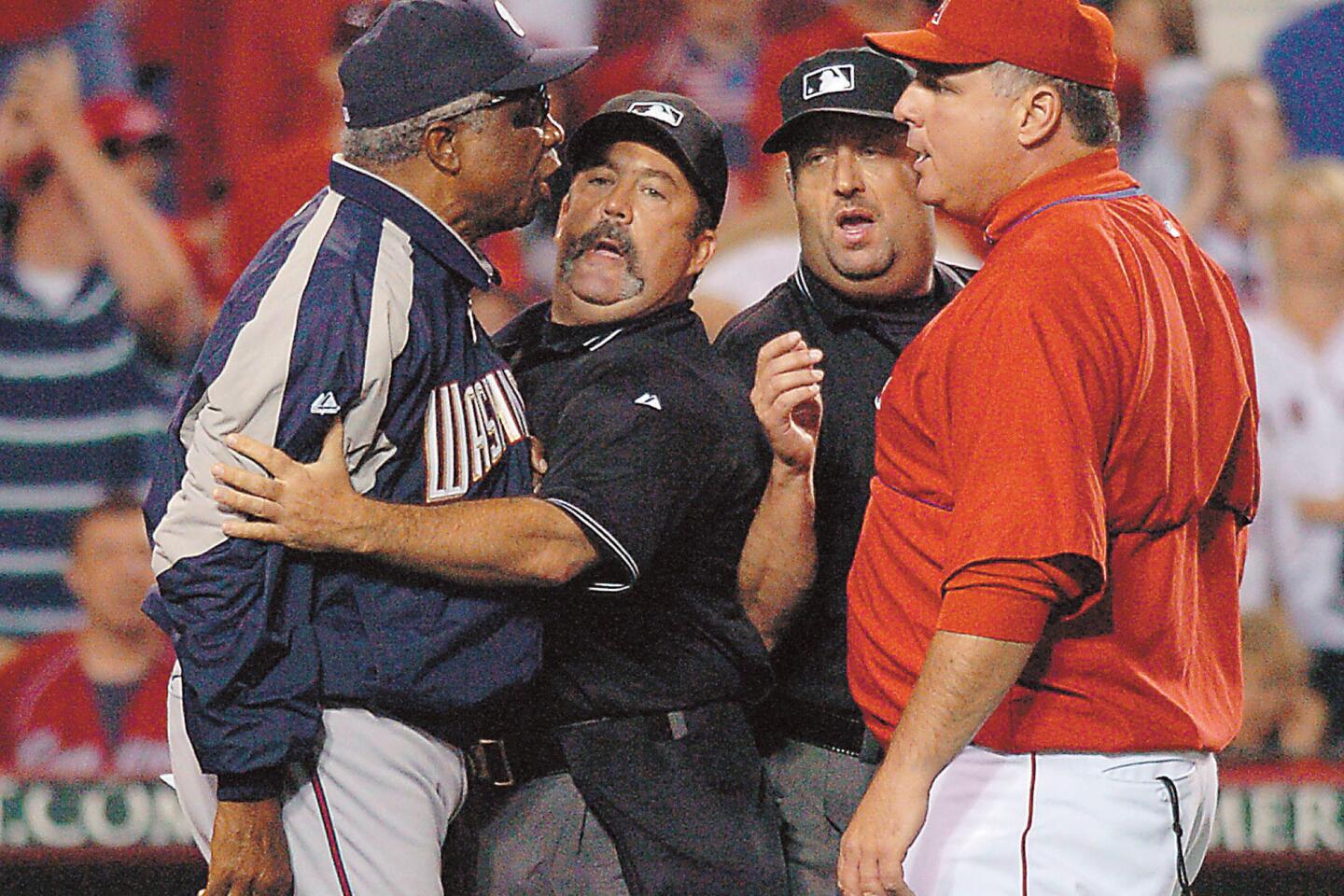

Robinson mellowed some in his later years, but the fiery competitor occasionally surfaced, most memorably during a heated argument with former Angels manager Mike Scioscia in Anaheim in June 2005.

Robinson had asked umpires to check the glove of Angels relief pitcher Brendan Donnelly. When pine tar, an illegal substance pitchers used to get a better grip on the ball, was found, Donnelly was ejected.

Scioscia approached Robinson, then 69, along the first-base line and threatened to have Nationals pitchers “undressed” in search of foreign substances. Scioscia turned his back to Robinson and began walking toward the Angels dugout, but Robinson followed him, countering with a few choice words of his own.

The two managers then stood at home plate, jawing at each other and angrily pointing in a confrontation that looked like it might turn physical. Players from both benches and bullpens stormed onto the field.

“I wasn’t going to let him intimidate me,” Robinson said the next day. “I am the intimidator.”

Robinson’s teams rarely had enough talent to contend for the pennant, and his first managerial job came with a woebegone Cleveland franchise that lacked the financial resources to compete.

But he prepped for that job by spending the previous five winters — during his off-seasons as a player — managing in Puerto Rico, and he knew if he turned down the Indians, baseball would have a built-in excuse not to offer such jobs to African Americans.

“Every time I put on this uniform,” Robinson said the day the Indians hired him, “I think of Jackie Robinson.”

Robinson, who went on to become a pioneer for blacks in the sport’s management and executive ranks, is one of only 13 African Americans to manage in the big leagues.

“He was willing to give up time and money by going to Puerto Rico to get experience so he could become the first black manager,” Weaver said. “A lot of guys wouldn’t do that. He had the intelligence to be able to do it. I was proud of him.”

Robinson is survived by his wife, Barbara Ann, who was a successful real-estate agent in Los Angeles, and two children, Frank Kevin and Nichelle. Services were not announced. According to MLB, the Robinson family asked that, in lieu of flowers, contributions can be made to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn., or the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Twitter: @MikeDiGiovanna

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.