California’s hottest surf spot is a Kelly Slater-designed artificial wave pool 100 miles inland

- Share via

Reporting from LEMOORE, Calif. — The wave rolls toward Jeremy Flores, gaining speed as it draws near, looking big and translucent and smooth as glass in the morning sun.

“All clean and perfect,” he says.

With just a couple of strokes, Flores pops to his feet and drives his surfboard into a bottom turn. Next comes a snap off the lip, his arms wheeling as he sets up the payoff.

The wave curls into a glossy barrel and he ducks inside, disappearing from view.

“It’s like a mirror in there,” the Frenchman says. “Super-fast.”

A surfer could spend his whole life — studying weather reports, driving coastal roads, scanning the horizon — to find conditions like these just once. But as soon as Flores finishes his pristine ride, another wave comes along. And another.

This isn’t your normal beach spot.

The WSL Surf Ranch is located 100 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean. The artificial wave pool, bordered by rows of eucalyptus and desert pine, is set amid acres of brown fields in this Central California farming town.

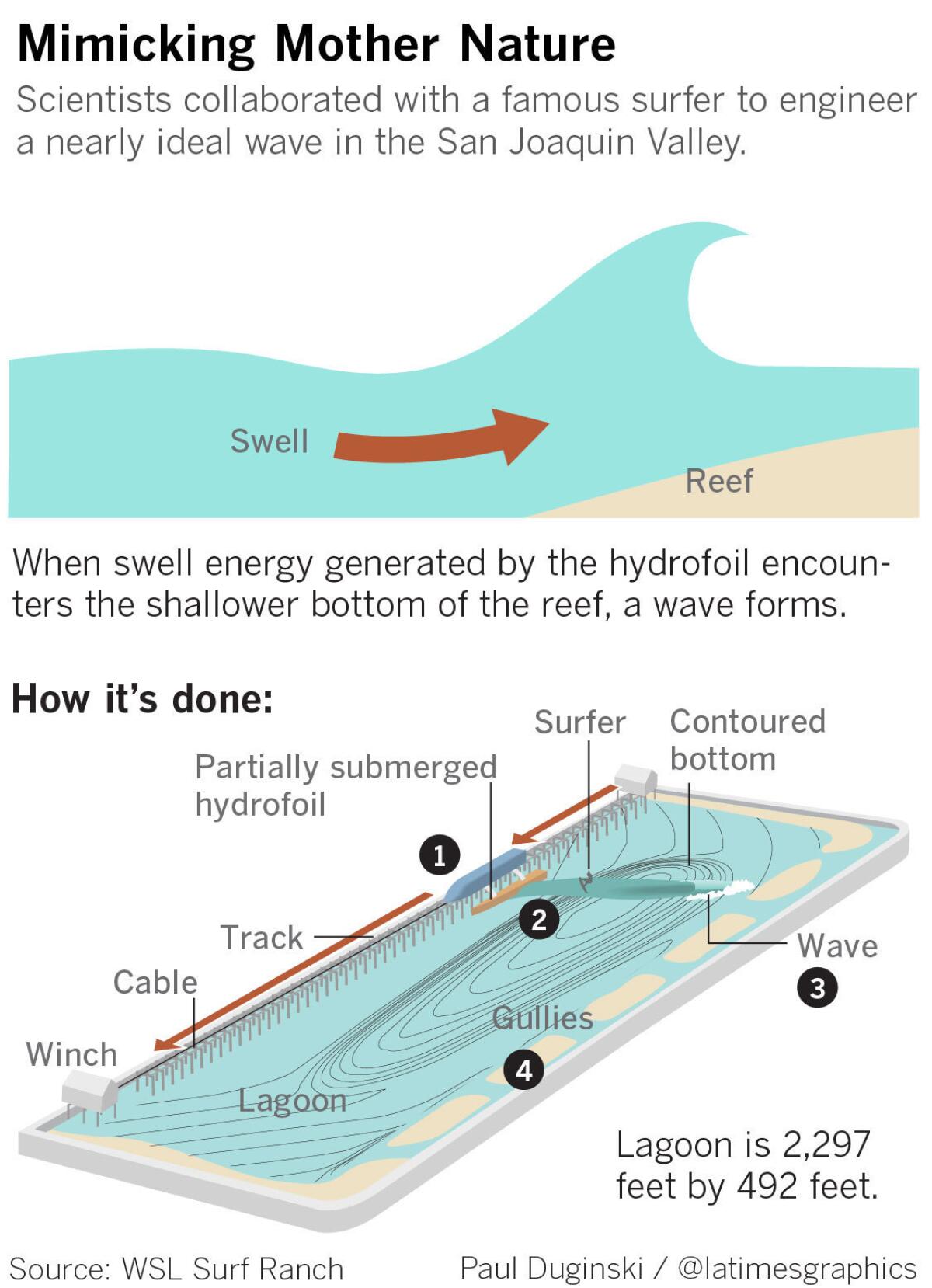

2. The swell energy reacts to carefully calculated bottom contours to form a wave.

3. The wave can have an open face on which surfers can make turns or create a barrel that surfers can ride inside.

4. Gullies along the side of the pool dampen turbulence and calm the water before the next wave is generated.

Purists have railed against technology intruding on their soulful pursuit, but that hasn’t stopped some of the world’s top riders from gathering in Lemoore this weekend, many of them flying to Los Angeles and driving three hours north into what feels like dusty, alien terrain.

They have come for a two-day contest that will serve as the ranch’s public unveiling. It is a chance to test the site’s whirring machinery, which can shape massive amounts of water, and perhaps glimpse at the future of the sport.

“For me, it’s never going to outdo a perfect day in Tahiti or Hawaii,” Flores says after his practice session. “But this is cool.”

::

So many years have passed since Kelly Slater began to wonder what this place might look like.

Long before he became the greatest competitive surfer in history, winning 11 world championships, Slater visited wave pools as a kid. In those days, they were puny, geared mostly toward a recreational clientele.

Still, he couldn’t get the idea out of his head.

“The mind was always spinning: How can you make this great artificial wave, what kind of technology would it take?” he recalls. “The idea was to make something that nobody had done before, a very high-performance wave.”

In 2006, Slater teamed with Adam Fincham, an associate professor of engineering at USC who specialized in fluid dynamics. They studied aerial footage of beaches across Southern California, Australia and the South Pacific, translating breaks into mathematical equations.

Computer simulations led to a small-scale model, each step suggesting they were on the right track, but it would be eight years before construction began.

The 20-acre Lemoore property seemed like a feasible site because the land was cheap and it already had a pair of long, narrow lagoons that had been used for water skiing. The isolation was another plus.

“It wasn’t on anyone’s radar that we were building here,” Slater says, adding that “if the thing didn’t work, we would scrap it all and never show anyone the footage and pretend it never happened.”

The key to their design was a giant hydrofoil — picture a bright blue locomotive with a snow plow mounted on it, a 200-ton contraption charging along rails at the lagoon’s edge, pushing a wall of water toward a lone surfer.

“In the ocean, you see the wave from 30 seconds out and you have all these judgments before it gets to you,” says Kanoa Igarashi, a 20-year-old pro from Huntington Beach who helped test the system’s early versions. “Here, the wave pops up out of nowhere. Pretty weird.”

After about two years of fine-tuning, the ranch now generates waves that consistently rise to 6 feet tall and roll the length of seven football fields. They break to the right when the hydrofoil moves in one direction, then left when it makes the return trip.

A curving hump on the lagoon floor — an artificial reef — produces alternating “performance” and “barrel” sections. Surfers can execute several turns, duck into the tube, emerge for more turns, get tubed again and still have time for an aerial maneuver at the end.

Additional submerged features and gullies help dampen the agitated water and real-time adjustments can change the speed and other aspects of the wave. Rides can last 45 seconds or longer — an eternity in surfing.

“My legs were crushed,” says Bianca Buitendag, a South African surfer making her first visit this weekend. “I went on a bottom turn and my knees just buckled.”

From afar, it all looks meticulous, with no bump or chop, no irregularities, but the velocity and push make for what Igarashi calls a “turbulent” barrel and wipeouts can feel like being tumbled in a washing machine.

“Yeah, they’re gnarly,” current world champion Tyler Wright says. “You get in wrong spot, you can definitely get water up your nose.”

::

As a longtime surfer who has written extensively about the sport, Matt Warshaw was invited to a private test at the ranch last year. He left with mixed emotions.

“It’s an engineering marvel,” he says. “We’re used to seeing mechanical waves that fall ridiculously short of what we’re looking for, but this thing almost exceeds what we ever imagined.”

Still, the author of the “Encyclopedia of Surfing” muses about a lifetime of searching for perfect waves, of gaining ocean knowledge while scrambling for moments of grace in an unpredictable, elusive environment.

“All the relationships we messed up, all the jobs we lost, all the school we ditched,” he says. “You could almost make it sound noble because that was your quest.”

A new generation of wave pools could render all of that unnecessary. Young surfers wouldn’t have to read tide charts or judge the effect of shifting winds or know which spots break hardest depending on swell direction.

The controversy surrounding the ranch reminds Aaron James, a UC Irvine philosophy professor and surfer, of an essential debate between Socrates and Callicles, a quarrel over the nature of desire and satisfaction.

“Surfers have a deep sense of ebb and flow, which is part of life,” says James, who wrote the book “Surfing with Sartre.” “The flow periods are joyous and exciting because you spent a lot of time chasing those waves.”

Cognizant of resentment in some quarters, Slater insists his creation has never been an either-or proposition.

“Even when I’m on the property, I’m still looking at swells in the ocean and my mind’s still going, oh, where do I want to go?” he says. “I might chase this thing down to Fiji. I might go to Samoa.”

The ranch is like a nutritional supplement, he says, explaining that “you’ve got to get your meal in the ocean and then come here and supplement it with some vitamins.”

The ramifications could be profound for professional surfing, which has always been vulnerable to the possibility of the sea going flat just as a major contest rolls into town.

“From a broadcast perspective, a fan experience, it can be tricky,” says Sophie Goldschmidt, chief executive for the World Surf League. “You don’t know when the good swells are going to come in, and we’re often in very remote locations that aren’t accessible.”

The ranch is opening just as the sport prepares for its Olympic debut at the 2020 Tokyo Games. Its arena parameters are TV friendly and let spectators stand close enough to be splashed by the waves that carry surfers past.

For competitors, the technology is enticing as a training ground.

An average pro surfer has 15 to 20 turns and maneuvers in his or her repertoire, Wright says. Practicing these moves can be difficult because the ocean rarely delivers uniform conditions from moment to moment.

“The one turn we want to practice, it could take 150 waves,” she says.

Competitions in high-performance wave pools might eventually resemble skateboard contests — if surfers know exactly what to expect, they can plan a series of tricks ahead of time.

“In the ocean, even if you want to do this crazy air, if you don’t have the right wave, you can’t really do it,” Flores says. “Here, if you deal with it right, you can do everything on the wave.”

::

A long line forms at the ranch’s entrance on Saturday morning, thousands of people filing inside for the start of the WSL Founders’ Cup of Surfing.

The crowd is mostly wearing board shorts and beach hats, with the occasional local wearing jeans and cowboy boots. Workers have gussied up the place, spreading tan bark across bare patches of dirt and erecting VIP cabanas along the far edge of the lagoon.

The WSL purchased the Kelly Slater Wave Co. two years ago, figuring it could give the league a boost. The contest is being touted as a coming-out party and, for the first time in league history, a major American network is broadcasting the competition live.

“This is a game-changer,” Goldschmidt says. “We can tell them at 8 o’clock in the morning we’re going to push a button and world-class waves are going to roll out.”

The 25 men and women surfers who have traveled to Lemoore are competing on mixed rosters representing the U.S., Australia, Brazil, Europe and the world, with the top three squads qualifying for Sunday’s final.

Much of the conversation here has touched upon dry inland air and cows in nearby fields, the relative merits of tradition and what this strange place could mean for surfing’s future.

But philosophical considerations tend to fade away when it comes time to ride.

All week there has been a giddiness among the competitors, who have often lingered at water’s edge, hooting for every good wave. They act like kids with a new toy, eager to get as many tries as possible.

After scoring a deep tube ride, Igarashi paddles to the cement beach and emerges from the water with a smile on his face.

“You’re definitely going to have fun here,” he says. “It’s Disneyland for surfers.”

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.