Bobsled designer races to craft a U.S. winner for 2014 Sochi Olympics

2014 Sochi Olympics: Designer Michael Scully hops on the U.S. bobsled team, making sleek, two-man sketches into speedy reality.

- Share via

There were no direct flights from Los Angeles, so Michael Scully took two planes and a ferry, then drove through upstate New York in the rain.

Tired and hungry, he stopped at a convenience store for coffee and whatever could be found to eat — in this case, he said, "a peanut-butter ice cream thing."

When Scully finally arrived at the U.S. Olympic training center in Lake Placid, two racers greeted him at the top of the hill with their bobsled.

"Glad you could make it," one of them said. "Now get in."

The next minute or so ranked among the most terrifying experiences of Scully's life. Scrunched between the bobsledders, he whistled down an icy, twisting track at more than 70 miles an hour, his body thrown from side to side, G-forces pressing on his shoulders.

"It just destroyed me," he recalled. "Halfway down, I really didn't know if I'd pass out."

Extricating himself from the sled, a bit shaken, he had all the inspiration he needed.

The 42-year-old is a creative director at BMW Group DesignworksUSA in Newbury Park. After spending much of his life building race cars, he has devoted the last two years to improving U.S. medal hopes at the 2014 Sochi Olympics.

The frightening ride with American pilot Steven Holcomb and brakeman Curt Tomasevicz represented a first step.

"That, for me, was jumping into the deep end," Scully said. "It's important to understand context."

The designer wanted to create a better bobsled.

Fluid dynamics. Vertical force. Turbulence and kinematics.

Any conversation on the topic of industrial design is bound to include technical jargon. Beneath all the physics and math resides a simple question that Scully calls "the designer's search for meaning."

"Why is something shaped the way it is?" he says.

His involvement with the bobsled team began in 2011, not long after BMW became a corporate sponsor for the U.S. Olympic Committee and several national federations that govern sports such as swimming and speedskating.

You’re looking to gain hundredths of a second. That’s all it takes to win.”— Steven Holcomb

Though the agreement involved financial support, the German automaker also offered its expertise. That sounded great to American sliders competing against European sleds built by the likes of Ferrari and McLaren.

"You're looking to gain hundredths of a second," Holcomb said. "That's all it takes to win."

Working in a bright, modern studio just north of Los Angeles — hundreds of miles from the nearest bobsled track — Scully began with rough pencil sketches. Inspiration struck at odd times.

"I don't sleep well," he said. "I have my clearest realizations when I'm having one of those middle-of-the-night episodes."

Early attempts focused on creating a sleeker profile with a lower center of gravity, deviating from the traditional bullet-nosed shape. He had to be mindful of international bobsled federation rules — lots of them.

Starting at the front of the sled and moving back, the federation sets interior and exterior measurements that must fall within a limited range. Scully said: "There are times when it feels claustrophobic from a design standpoint."

He began sketching on top of federation diagrams to stay close to the requirements. Next came a more refined drawing and, after that, an array of 3-dimensional designs, each slightly different.

These virtual sleds were subjected to computational fluid dynamics — a sort of digital wind tunnel. The computer showed which one moved through the air most efficiently.

Steven Holcomb takes training run with the USA-1 sled before the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. (Michael Sohn / Associated Press)

The BMW crew, which grew to include a modeler and engineers, took the winning shape and began to tinker.

Each slightly modified design required about a day to produce on the computer; test results would be ready by morning. The crew worked its way through 69 iterations.

"This has been the most intensive project of my career," Scully said. "I will confess, I loved it."

Speed always intrigued him.

As a teenager growing up in New Hampshire, Scully switched from skiing to snowboarding. Unlike most kids fascinated by the halfpipe and aerial tricks, he gravitated toward slalom racing.

His talents earned him a sponsorship but when he looked ahead — snowboarding was not yet an Olympic sport — the future seemed limited.

There followed a listless year at two colleges. Schoolwork proved far less interesting than his new hobby, modifying and racing sports cars.

This did not thrill his family. His father was an architect and his grandfather was the noted Yale professor and architectural historian Vincent Scully.

In the fall of 1992, Scully found a way to combine academics with his need for speed. He enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh to study industrial design and the art of making cars go faster.

There is a clarity with any type of racing project. The purpose is very defined.”— Michael Scully

"There is a clarity with any type of racing project," he said. "The purpose is very defined."

For the bobsled project, BMW concentrated on the two-man sled, which seemed like a good fit for a sports car maker. Besides, the four-man version was already being produced by former NASCAR star Geoff Bodine, who had helped the U.S. win medals in that event.

Super-light carbon fiber allowed Scully to play with weight distribution for better handling. Having experienced the violent shaking and thunderous roar of a bobsled run, he also sought to make the new sled run smoother and quieter so pilots could drive more precisely.

The first prototype arrived at the Olympic track in Park City, Utah, in March 2012.

The sled had a sharp nose, slim body and swept-back tail. BMW has never divulged the dimensions, but international rules mandate a minimum wheelbase of 5.5 feet and a maximum weight of 860 pounds with both athletes aboard, the driver sitting low with the brakeman ducking behind him.

As the racers gathered around, Scully looked at the 6-foot-3, 205-pound John Napier and wondered if he had made the interior too narrow.

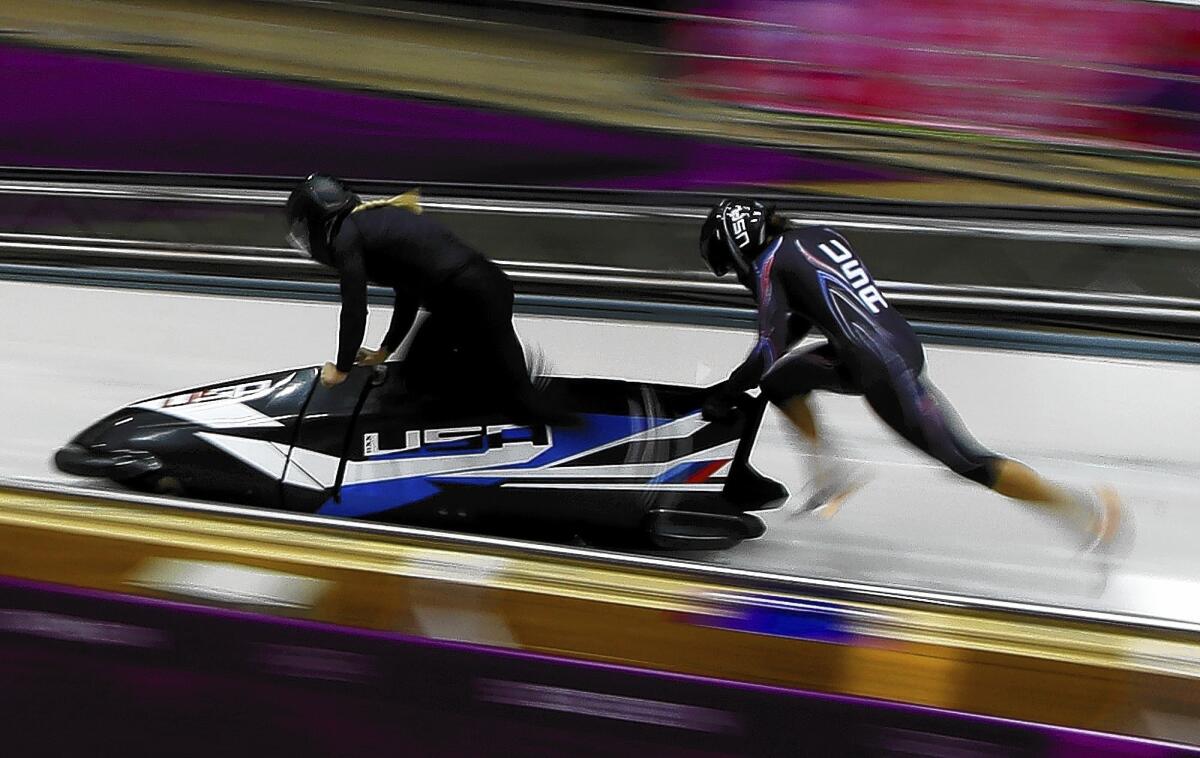

The USA-2 sled, piloted by Jamie Greubel, starts a run during a training session for the women's two-person bobsled at the 2014 Winter Olympics. (Dita Alangkara / Associated Press)

"I thought there was no way he could fit into this thing," Scully recalled. "He hopped in and said he'd never been more comfortable."

The athletes were keen for better equipment. Though Holcomb won the four-man at the 2010 Vancouver Games, American men hadn't earned gold in the two-man since 1936.

U.S. Coach Brian Shimer explained to Scully: "If the sled's fast, they'll find a way to fit."

The time had come for a test run, and now it was Holcomb's turn to worry.

"It's a little nerve-wracking when you've got a new builder," he said. "We had to take it off the top and see if we could get to the bottom."

The clock was ticking, and the Olympics were drawing nearer.

Those initial trials presented only minor glitches — including a small bolt that vibrated loose — but Scully and his crew kept fiddling with the design.

In January 2013, they sent a new version to Austria where the Americans were competing on the World Cup circuit. Instead of practicing with the prototype first, an eager Holcomb raced it the next day.

On his first run, he jumped in and snagged a steering line with his foot, bouncing his sled off the wall and losing precious seconds. Scully, who had grown accustomed to waking up at 3 a.m. to watch the races online, said: "That just killed me."

His economic design left scant interior room. After the push start, the pilots and brakemen had to align themselves perfectly while jumping in.

Jamie Greubel pilots the women's USA 2 bobsled during practice in Sochi. (Streeter Lecka / Getty Images)

None of them complained. They were more interested in the steering mechanism, which can be surprisingly complex despite the fact that pilots turn by tugging on D-rings connected to ropes. Holcomb kept pestering for a linkage that would improve feel and response.

"The way it handles through the curves, the way the back end rides," he said. "I appreciated that Michael didn't punch me in the face every once in a while."

In fact, the designers wanted all the feedback they could get for last-minute alterations. BMW will say only that it made a "significant investment" in delivering the final six sleds — three for the men, three for the women — to the U.S. team trials last October.

Elana Meyers, a top pilot, survived a dicey moment while banking too high on a turn in practice. Later, she posted the fastest time for the women and recalls thinking: "I love this sled."

She and Holcomb medaled at a World Cup race in Calgary the next month. The American men and women swept the podium at separate events in December.

"Last year, I'd get to the bottom [of a run] and think there was no way I could have driven any better but my times weren't fast," Meyers said. "Now, I can make mistakes and still win."

The U.S. team will get more practice at Sanki Sliding Center in the mountains above Sochi. When its Olympic competition begins on Feb. 16, bobsledders will be gambling on equipment that still feels relatively new.

Scully plans to travel to Russia to watch his babies — the sleds, not the athletes — in action.

Follow David Wharton(@LATimesWharton) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Son of a Holocaust survivor searches for a lost Nazi diary

Porn's XBiz Awards an uninhibited affair

Winning an award will help me feel like I am the best at what I do.”

A precarious time for Afghan women

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.