- Share via

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and stalled runner Allyson Felix’s preparations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics — which she planned as her fifth and last — she had to find new ways to squeeze in her workouts.

UCLA’s track and other favorite sites were off limits, sending Felix to the beach, parking lots and anywhere her coach, Bobby Kersee, could find open ground. Driven to improvise, Kersee turned the area near Felix’s Santa Clarita home into a makeshift track, drawing curious neighbors to see what the commotion was when he marked off distances and barked orders.

It was a surreal scene for Felix, who was 18 and a year out of L.A. Baptist High when she went to the 2004 Athens Olympics and won the first of her nine Olympic medals.

“The craziest experience was just training in my neighborhood. I’ve gone for runs before in my neighborhood, but I never have sprinted through the streets,” she said.

Fortunately for her neighbors, her high school — now called Heritage Christian School — invited her to train on the track it had named for her. She appreciated the poetic symmetry of taking a joyful loop back to her beginnings as she approaches the finish line of her brilliant career.

“That was really special because my grandfather, who lived to 107, came to the naming of it and that is very memorable to me,” she said of her mother’s father, Whalen Jones, the founding pastor of Messiah Baptist Church in Los Angeles. “It’s funny how it’s come full circle.”

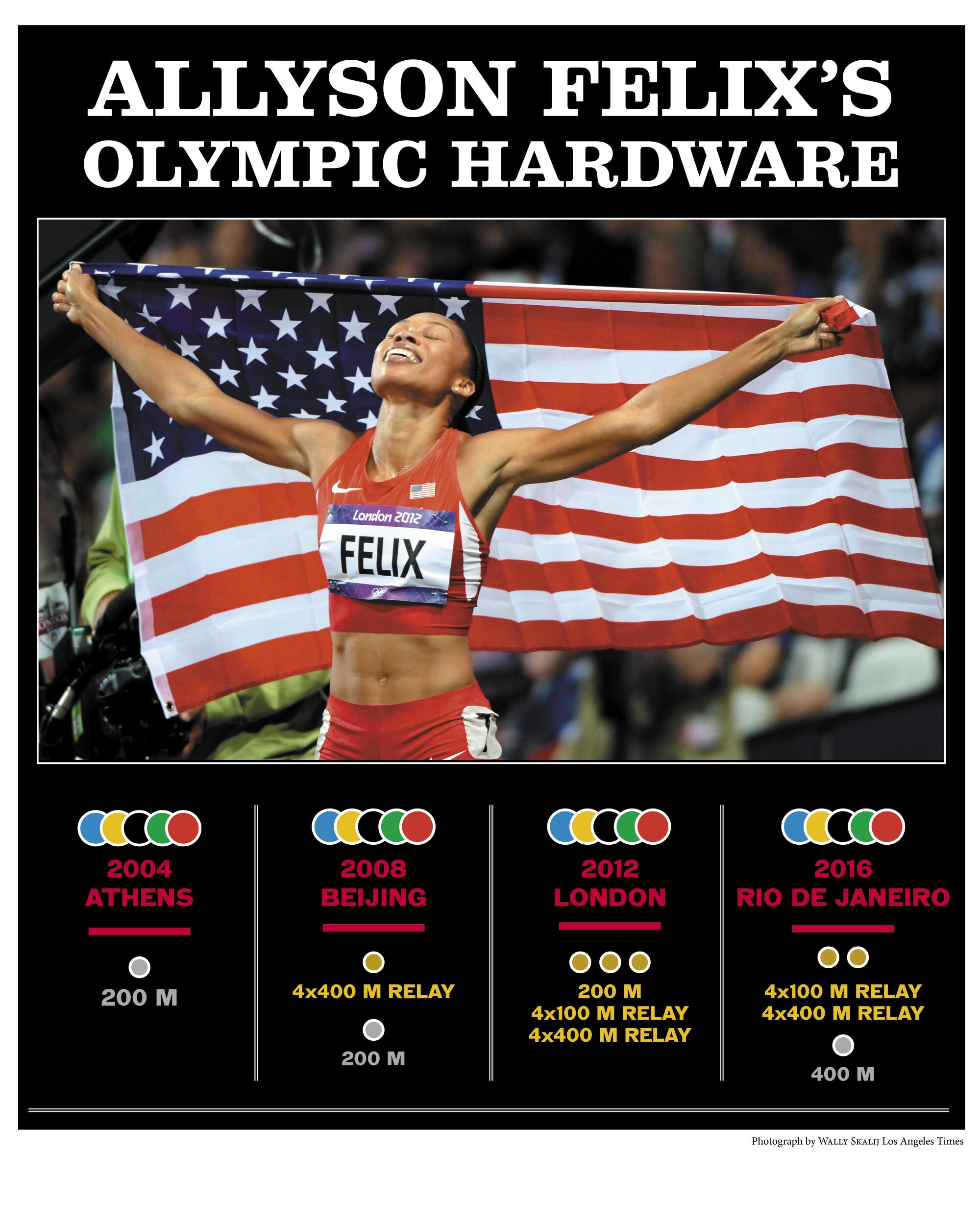

A shy preacher’s daughter who was nicknamed “Chicken Legs” and reluctantly gave up high school basketball for track, Felix has soared on the wings of her steadfast faith and rare talent. Her six Olympic gold medals are the most won by a female track and field athlete. With nine medals overall — second among American track and field athletes to Carl Lewis’ 10 — she’s tied with Merlene Ottey for the most Olympic track and field medals won by a woman. In 2019, Felix became the most decorated track and field athlete at the World Championships when she won her 12th and 13th gold medals and improved her record total to 18.

“I think Allyson Felix is, above all, America’s favorite track star and she’s been that, I think, for most of her career,” said Ato Boldon, an NCAA sprint champion at UCLA and four-time Olympic medalist for Trinidad and Tobago who does track and field commentary for NBC.

“She’s defied all the odds. There are a ton of high school prodigies who turn pro and are never heard from again, but in Allyson we have somebody who made the jump in high school. Back then, people thought it was the worst thing she could possibly have done, go pro and not have the NCAA system to groom her. She’s had one of the most remarkable careers of anybody in the history of the sport.”

The girl whose competitiveness was questioned because of her quiet nature had an inner fire that still blazes. She now carries that passion beyond the track, using her experience of prematurely giving birth to daughter, Camryn, by emergency caesarean section in 2018 as inspiration to fight for female athletes’ rights and better maternal health care for Black women and those who lack access to such vital treatment.

When Nike refused to guarantee it wouldn’t penalize her if she ran less than her best before and after her pregnancy, she joined other prominent female runners to bring about industry-wide change. She has a woman-friendly sponsor in Athleta and favors endorsements that allow her to advance her interest in child and family issues. She’s featured in a Procter & Gamble advertising campaign themed, “Your goodness is your greatness,” about the importance of parents’ involvement in their children’s lives. In one ad she combs her daughter’s hair, recreating the bond she had with her mother, Marlean.

“For me, being Cammy’s mom is the No. 1 job that I have. It’s my biggest accomplishment and it’s amazing,” Felix said. “It’s been also really challenging trying to figure out how to do both at the same time. But I’ll be able to look back and tell her about this journey that she’s been on as well.

“It hasn’t been an easy one. There’s been a lot of fights, a lot of challenges along the way, but she has been the driving force to be able to get through that and she’s really helped me find my voice and allowed me to do things bigger than wanting to run fast.”

In a sport too often tainted by cheating there has never been a whisper about Felix, who has voluntarily undergone extra drug testing to prove it’s possible to be clean and excel. Her impeccable character was a key reason Jackie Joyner-Kersee, a six-time Olympic medalist who ranks among the greatest all-around female athletes, became Felix’s mentor nearly two decades ago.

“In sports, sometimes we define by how fast or how far we might jump or run but I just think the human side of her, the compassion that she shows for everyone and also understanding about being patient, that makes her great,” said Joyner-Kersee, who is married to Felix’s coach and often sends Felix encouraging notes that balance Bobby Kersee’s occasional gruff words.

“I always believed that Allyson was always the quiet storm. It was just a matter of time. You see this petite young girl running, but there is a killer instinct within her to be the best.”

Felix, 35, is competing at the U.S. Olympic trials in Eugene, Ore., for berths in the 200- and 400-meter races and a spot in the relay pool in the delayed Tokyo Games. She improved her season-opening time in the 400 from 50.88 seconds to 50.66 in late May, among the top 15 in the world this year. In the 200 she ran a wind-aided 22.26 seconds to finish second at Walnut, Calif., on Mother’s Day. Camryn was in the crowd and wore a shirt that declared, “My mom is faster than your mom.” That surely erased the sting of Felix’s loss to 24-year-old Gabby Thomas, who won in 22.12 seconds.

She’s optimistic about her chances at the trials and smart enough not to take anything for granted. The final of the 400 will take place on Sunday; the first round of the 200 is scheduled for Thursday.

“I just go in like I’ve never done anything before. To me, you just can’t get ahead of yourself,” she said. “I guess I would say I’m very determined. I feel good. But Olympic trials is top three on that day and nothing is certain.”

Ryan Lochte finished seventh in the 200-meter individual medley at the U.S. Olympic swimming trials Friday night, missing his chance to compete in Tokyo.

Boldon sees Thomas and Sha’Carri Richardson as major obstacles to Felix’s hopes in the 200.

“I think that this year is going to be incredibly challenging for her because I’m not sure that the 200 is the easiest path for her both at the U.S. level and certainly at the Olympic level,” he said. “She’s not a lock to make the team.”

He anticipates Felix having better Olympic medal chances in the 400 because defending gold medalist Shaunae Miller-Uibo, who outleaned Felix to triumph in Rio in 2016, likely will focus on the 200 instead.

No matter what happens at the trials or in Tokyo, Felix’s athletic legacy is secure. Her impact on the world could be equally impressive when she retires from competition and plunges more deeply into the cause of reducing maternal mortality rates among Black women.

“Yes, people will talk about the accolades. They will talk about the medals,” Joyner-Kersee said of how Felix will be remembered. “But more important, they will talk about the human, and the human factor, and how she was able to connect on so many levels in so many different genres, and that will continue. Once she’s no longer running, people will still, in my opinion, gravitate to her because they know she can help them be better in what they’re doing.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.