- Share via

ST. LOUIS — The massive canopy rises from the Los Angeles landscape, providing cover for the spectacular stadium beneath it. The Rams spared no expense in constructing their glorious new home, and they spared no adjective in describing it.

“SoFi Stadium is an unprecedented and unparalleled sports and entertainment destination,” the stadium website declares.

It is the destination for the next Super Bowl, the first in the Southland since 1993, a celebration of America’s most popular sport in America’s capital of creativity.

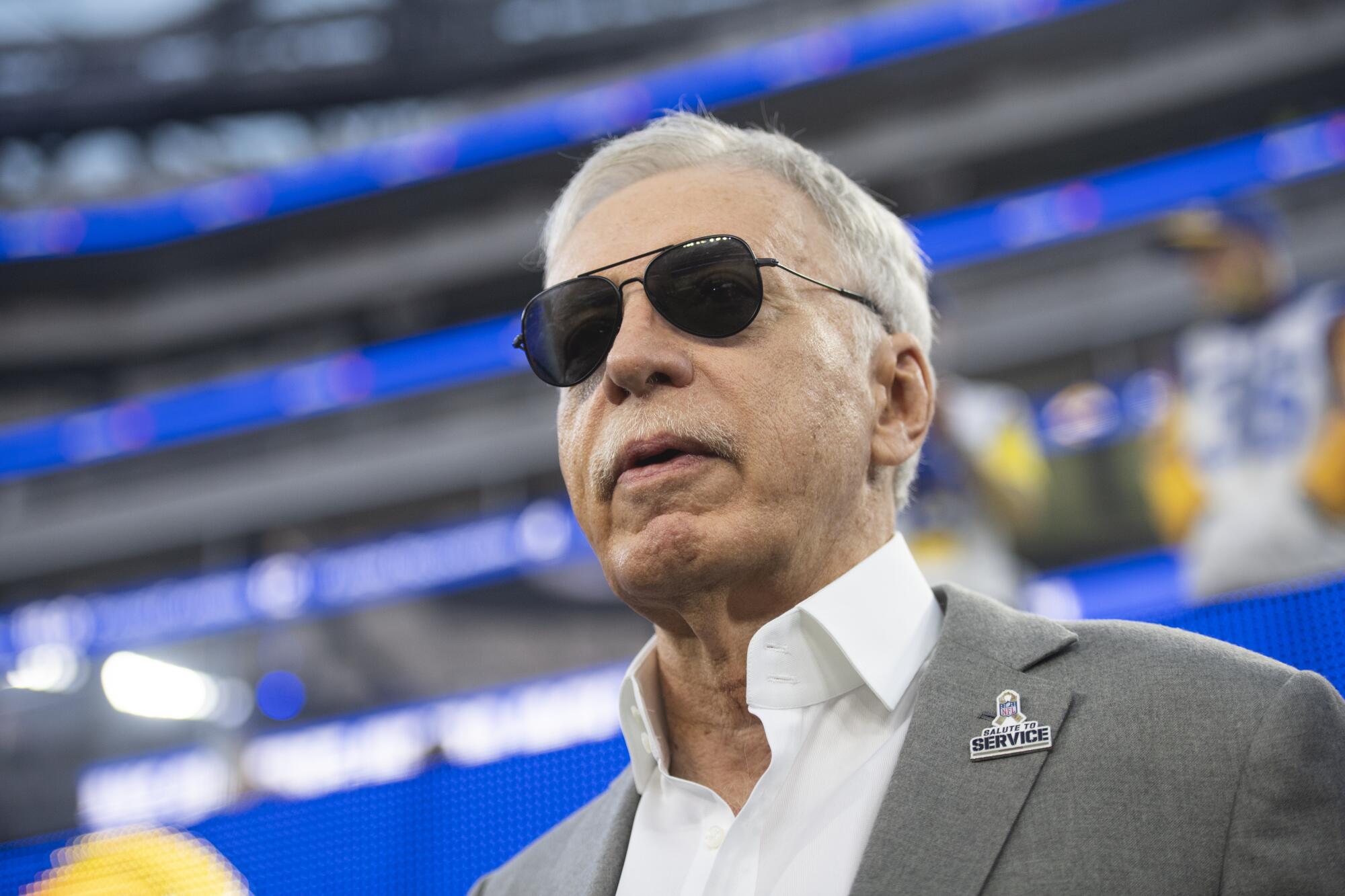

“We are driven, and our ambition deserves a stage,” the website video trumpets. “That stage is SoFi Stadium … built from the vision of Stan Kroenke.”

As Kroenke’s vision turned into reality, a performing arts venue rose next to the stadium. So did a West Coast hub for NFL operations.

The Olympic Games are coming to the stadium. So is college football’s national championship. So is a bowl game named for late-night jokester Jimmy Kimmel. The Chargers have moved in.

SoFi Stadium, the NFL’s crown jewel, was the the culmination of Rams owner Stan Kroenke’s vision and the NFL’s desire to return to the L.A. market.

Above all, the stadium is the home of the NFL team Kroenke owns, the one that called L.A. home before the Dodgers or Lakers did.

When Kroenke wanted to bring the Rams back home from St. Louis, amid three teams jockeying for rights to the L.A. market, the Rams excerpted a column from The Times’ Bill Plaschke in their relocation application.

“The Rams are family. The Rams are legacy,” Plaschke wrote in 2015. “The Rams were our first major pro team. They were our first big crush. They were our first Showtime ... the first marriage of sport and Hollywood, the first pro team to truly love L.A. ... They would be welcomed home.”

But what if they should not have come home? What if the NFL relocation process was a sham? What if the NFL did not follow its own rules, and if Kroenke and the Rams rigged the system?

Those are the allegations made in St. Louis, where the Missouri-born Kroenke is considered less of a visionary and more of a rapacious turncoat.

What appeared to be sour grapes from a scorned city four years ago is turning into a nightmare for Kroenke and the NFL, as a longshot lawsuit heads toward trial in January, just in time to steal headlines from the Super Bowl at Kroenke’s showcase stadium Feb. 13.

After a series of pretrial rulings in favor of St. Louis, Kroenke has turned on some of his fellow NFL owners, and on the league itself. His football palace in L.A. cost $5 billion. He might need to come up with another billion, or more, to rid himself of St. Louis.

::

Major League Baseball enjoys an exemption from federal antitrust law, providing the league with sole control over where its teams play. The NFL has no such exemption.

In 1982, the Raiders moved from Oakland to Los Angeles. The NFL owners had voted against the move, and the league had unsuccessfully challenged the move in court. In 1984, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals said the league was subject to antitrust law but could protect itself in the future by adopting “objective guidelines to govern team relocation.” The NFL did just that.

On April 12, 2017 — 16 days after NFL owners approved the Raiders’ move from Oakland to Las Vegas, and 15 months after NFL owners approved the Rams’ move from St. Louis to L.A. — St. Louis sued. Oakland later sued too.

In both cases, the NFL argued the relocation guidelines represented a league policy, not a binding contract. No city was a party to the policy, the league contended, and so no city had grounds to challenge whether the NFL had properly abided by guidelines in which a relocation decision is defined as the league and its owners making “a business judgment concerning how best to advance their collective interests.”

The league argued that both cases should be thrown out of court. The Oakland case was, although an appeal is in progress.

The St. Louis case was not. St. Louis Circuit Court Judge Christopher McGraugh ruled that the relocation policy was akin to a contract in that it “contains obligations and promises that may be enforceable in a court of law” and that “many provisions of the relocation policy were intended for the benefit of a club’s home territory.”

“You have an aggrieved party. This happens in every aspect of life, when parties separate. …They’re upset. And they want to take it out on the person that they feel wronged them. What you typically don’t have is a judge helping in that process.”

— Sports consultant Marc Ganis

Kroenke and the Rams were denied. St. Louis had alleged Kroenke and the Rams had breached a contract rather than negotiate in good faith, and the city now had judicial blessing to pursue its case.

In 1999, in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, then-NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue all but said the league indeed had struck a deal with its host cities. Tagliabue testified the NFL had “come to an understanding on issues of franchise movement” with the U.S. Conference of Mayors (USCM).

Marc Morial, then mayor of New Orleans and now president of the National Urban League, said he and a USCM task force had worked with the NFL so that no team could just bolt its city, as the Colts had done to Baltimore and the Browns had done to Cleveland.

“We negotiated with the National Football League a set of franchise relocation guidelines, which had as their intention to give local communities and cities a voice,” Morial told The Times.

“It did not give cities an absolute veto. We created a process.”

That process, Morial said, was intended to balance the rights of owners to run their business as they saw fit with the rights of communities that often had spent tax dollars to build stadiums, and to protect the companies and workers who benefited from having an NFL team in town.

Tagliabue introduced into the Senate hearing record a letter to Morial from NFL vice president Joe Browne, in which Browne wrote that the process would ensure “franchise moves occur only after exhausting all reasonable options in a team’s existing home territory.”

::

The deal that lured the Rams from Anaheim to St. Louis in 1995 included a commitment to maintain a new domed stadium in line with the “first tier” of NFL stadiums around the country. In February of 2013, after years of negotiations had failed, arbitrators ruled that the Rams’ proposed $700 million in improvements would restore the stadium to “first tier” status and that St. Louis’ proposed $124 million in renovations would not.

If St. Louis had agreed to make those improvements, the Rams would have been bound to another decade in the dome. However, in July of 2013, St. Louis officially declined to make those improvements.

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell sees culmination of getting football back in L.A. with a crown jewel stadium. Here’s how one memo set it in motion.

That gave the Rams the right to convert their lease to year-to-year and then leave town. They did.

The Rams and the NFL declined comment for this story. St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones was unavailable for comment, her spokesman said. Brian McMurtry, executive director of the St. Louis Regional Convention and Sports Authority, which joined the city and county in suing, did not return a message seeking comment.

In a 2016 interview with The Times, Kroenke said he “really started looking hard” for a new home in the summer of 2013 and became enchanted with the Inglewood location, on the site of the Hollywood Park racetrack. Kevin Demoff, the Rams’ chief operating officer, told The Times that Kroenke called him and said, “This is an unbelievable site.”

Said Demoff: “There are moments in your life you never forget.”

Kroenke purchased the land in 2014 and unveiled stadium plans for the site in 2015.

St. Louis countered with a proposal for a new riverfront stadium but alleged that the Rams did not participate in negotiations and that the NFL offered less league funding for that plan than for stadium plans in other cities.

In its evaluation of the Rams’ relocation bid, the NFL categorized the overall financing for the St. Louis proposal as uncertain and, in any case, claimed the Rams had been presented with “an offer less favorable” than the expiring lease on the existing domed stadium.

The relocation policy does not grant cities a right of first refusal or provide explicit standards for a city to meet, and it specifically allows teams “to discuss a possible relocation, or to negotiate a proposed lease or other arrangements, with a community outside its home territory.”

“Nobody wants Stan Kroenke back in St. Louis.”

— Pollster Braxton Payne

St. Louis alleges that Kroenke and the NFL strung the city along in discussions for a new waterfront stadium, knowing the team would move to L.A. while letting St. Louis run up millions in expenses for planning its proposed stadium. The Rams and the league deployed the relocation guidelines as a fig leaf to “disguise the avarice and anticompetitive nature of the entire proceeding,” the city claims, rather than negotiating in the good faith required under the policy.

The Rams dispute that they were obligated to negotiate for a new stadium.

Under the relocation policy, the NFL considers whether a team has afforded a city “a reasonable amount of time to address pertinent proposals” to keep the team. St. Louis had more than a decade to either reach an agreement on renovations to the domed stadium or implement the $700-million plan, the Rams say. In their relocation application, the Rams alleged St. Louis was “in no position to claim that the Rams have not exhausted all efforts to meet the NFL’s relocation guidelines.”

When McGraugh allowed the case to proceed, the city promptly demanded documents and depositions from Kroenke, commissioner Roger Goodell and other league owners and officials. There is concern in league circles that the discovery process could have turned up documents in which Chargers and Raiders officials — in trying to win NFL approval for their proposed stadium in Carson — outlined how they believed the Rams might not have been in compliance with the relocation policy, according to people familiar with the case not authorized to speak due to the ongoing litigation.

One uncomfortable document already has been disclosed in court. Before the NFL owners voted on whether the Rams would be permitted to move to Los Angeles, Rams staffers had prepared a farewell letter to the fans in St. Louis. Within the Rams’ offices, the document was known as the “AMF letter.”

AMF stood for “Adios, Mother F—.”

::

That feeling appears reciprocal. In 2010, as St. Louis noted in its lawsuit, Kroenke said, “I’m going to attempt to do everything that I can to keep the Rams in St. Louis. … I’ve always stepped up for pro football in St. Louis.”

In three years, he had found a new home for the Rams. In another three years, they were gone.

“You have an aggrieved party,” said Marc Ganis, a Chicago-based sports consultant who works closely with the NFL and its owners. “This happens in every aspect of life, when parties separate. You have one that feels they’re angry about it, and the other has moved on. Whether that’s a marital divorce or a business partnership, it’s the same thing. They’re upset. And they want to take it out on the person that they feel wronged them.

“What you typically don’t have is a judge helping in that process.”

Before NFL owners would vote on the proposals for L.A. stadiums, league officials demanded the owners of all three interested teams sign indemnification agreements. The owners of the Chargers, Raiders and Rams thus promised to cover the “costs, including legal fees and other litigation expenses,” to defend any challenge to a move of their particular team.

We visited all four concession stands at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. Here’s our guide to the best and worst food we ate during a recent Rams game.

In America, litigation is a cost of doing business. The NFL and its owners fully expected that any litigation challenging a franchise move would be promptly dismissed, and indeed the Oakland case was.

In St. Louis, Kroenke and the NFL asked McGraugh to throw out the lawsuit, to order the dispute into private arbitration, and to move the suit out of St. Louis. McGraugh denied all three requests. None of those rulings were overturned on appeal.

He also ordered Kroenke and five current and former owners involved in the relocation process — including the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones and the Patriots’ Robert Kraft — to submit personal financial information that a jury could use to determine potential punitive damages.

The NFL appears resigned to losing in McGraugh’s courtroom, with the hope of winning on appeal. The financial damages could be massive.

St. Louis has asked to be awarded the $550 million that the Rams paid the NFL as a relocation fee, as well as the increase in the franchise value since the move.

Forbes estimated the Rams’ franchise value at $1.45 billion in 2016, just before the Rams moved, and at $4.8 billion in 2021.

The biggest tease in this latest NFL news isn’t that another rich guy is planning to build another stadium on another perfect site like Hollywood Park.

Throw in the tax revenue St. Louis lost when the Rams moved, and damages could top $4 billion, independent of any punitive damages.

There is no guarantee that even a hometown jury would award anywhere near that much money, but the risk could compel a settlement of at least $2 billion, said Patrick Rishe, who teaches sports business at Washington University in St. Louis.

Kroenke initially offered $100 million to settle, according to Front Office Sports. He now believes the case can be settled for $500 million to $750 million, according to Sports Business Journal.

The indemnification agreement gives Goodell the final say on who owes what. However, Kroenke could sue the NFL if Goodell tries to compel him to pay damages should a jury find he violated a relocation policy with which the league said he had complied. Kroenke has informed his fellow owners he does not believe the legal “costs” covered under the indemnity extend to damages, and he has asked them to share in the cost of a settlement.

“Right now, I think they want to roast Stan, figuratively and literally,” Rishe said.

In St. Louis, where coverage of the lawsuit figures prominently on nightly newscasts and talk radio, victory is in the crisp autumn air. The lordly NFL could be brought to heel, either with a 10-figure payment or a trial in which Kroenke and Goodell could squirm uncomfortably on the witness stand.

A local pollster surveyed residents this month on their desired outcome: a billion-dollar settlement, a jury trial, an NFL expansion team, or an existing NFL team relocating to St. Louis.

However, when pollster Braxton Payne asked about interest in an existing NFL team moving here, he asked specifically about the Chargers. He did not ask whether residents wished for the return of the Rams.

“Nobody,” Payne said, “wants Stan Kroenke back in St. Louis.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.