Column: Las Vegas’ monopoly on marquee boxing matches ends, but it remains a popular venue

- Share via

The excitement in Richard Schaefer’s voice was palpable.

“Look what happened with the Las Vegas Golden Knights,” Schaefer said. “Go watch a hockey game in Las Vegas. It’s almost like a different sport.”

He went on like this for a while, mentioning that he expected the city to embrace the Raiders when they start playing there this year.

Schaefer is a boxing promoter. Yet here he was, talking up competing sports in a market instrumental to his business.

At this stage, there’s no point in denying the obvious: Boxing is in a period of transition.

“No question about it,” said Schaefer, who has promoted major fights involving Floyd Mayweather and Oscar De La Hoya.

The sport has adjusted by taking its major events elsewhere.

Mikey Garcia’s failed attempt to dethrone Errol Spence was held in Dallas. Heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua’s upset loss to the Andy Ruiz Jr. was in New York. Joshua avenged the defeat and regained his titles in Saudi Arabia. The two best fighters in the world at any weight class, Terence Crawford and Vasiliy Lomachenko, fought a combined four times in three cities: Los Angeles, New York and London.

Don’t misinterpret the development as a sign of boxing abandoning Las Vegas. It remains the fight capital of the world.

The sport’s top attraction, Canelo Alvarez, fights almost exclusively there. The widely anticipated rematch of the dramatic draw between Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury also will be staged in the city.

“I think every fighter’s dream is to eventually fight in Las Vegas,” Schaefer said.

A roundup of new hotels, name changes and renovations coming to Las Vegas in the year ahead, along with a few other key visitor attractions.

The history of boxing in Las Vegas extends back to the middle of the 20th century. The city’s first major fight was in 1955, when 41-year-old former light heavyweight champion Archie Moore moved up to heavyweight to take on Nino Valdez at Cashman Field, a baseball stadium that remains in use today. There was controversy from the start, as Moore won a disputed decision.

Las Vegas staged its first championship match five years later, in 1960, at its new convention center. Benny Paret won the welterweight title by defeating Don Jordan in a 15-round unanimous decision.

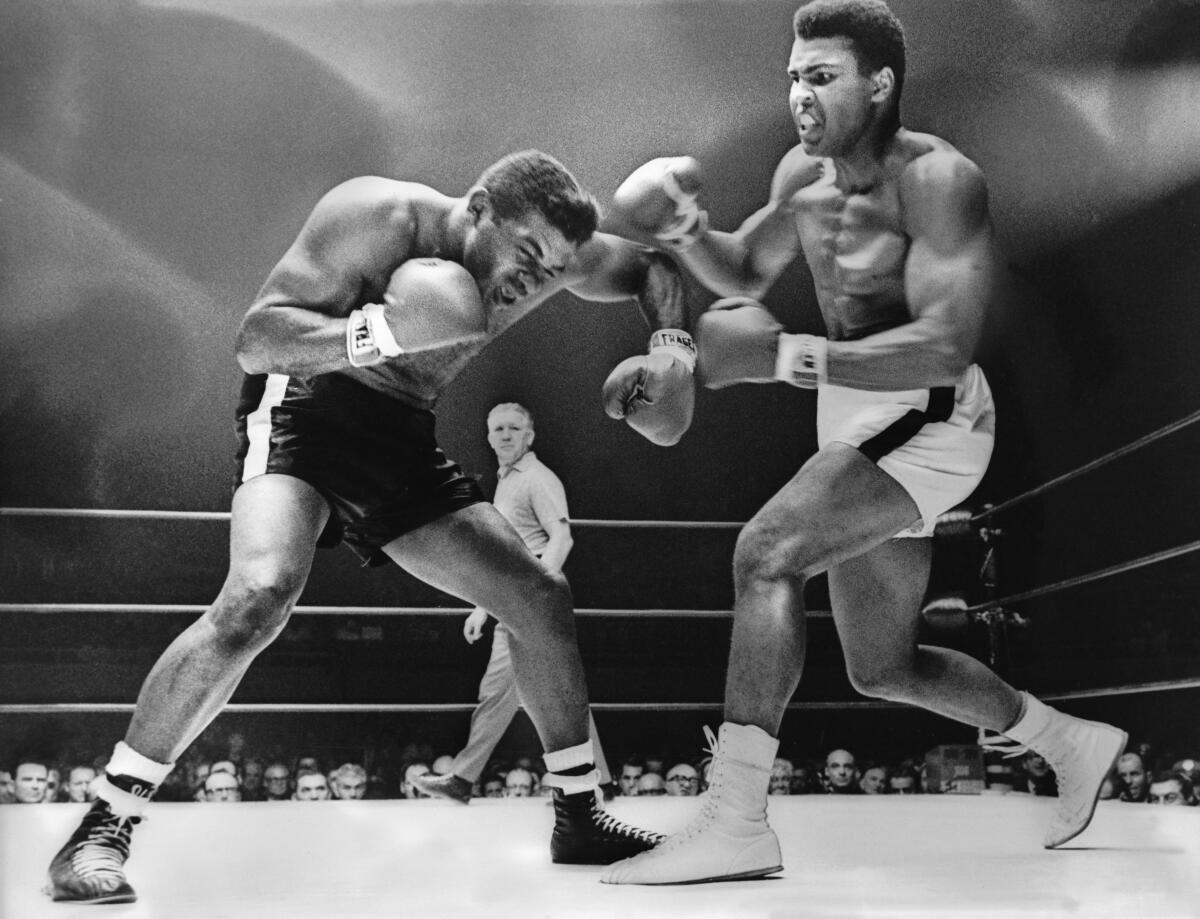

Paret’s victory was the first of 14 championship fights at the Convention Center over the next seven years, including Sonny Liston’s and Muhammad Ali’s knockout victories over Floyd Patterson.

The publicity from the fights provided national exposure for the casino town in the middle of the desert.

“People need an excuse to go to Vegas, get drunk, gamble and have sex with strange people,” longtime boxing publicist Bill Caplan said. “A fight gives you an excuse to do all that.”

Caplan, who is in his seventh decade of watching fights in Las Vegas, recalled how casinos used to have boxers work out on their properties to attract gamblers.

Soon, the casinos started hosting fights. Once that happened, venues in other cities couldn’t compete for major boxing shows. Knowing a highly anticipated match would increase their gaming revenues, casinos were in position to offer promoters extravagant site fees. This typically consisted of casinos guaranteeing millions of dollars in ticket sales.

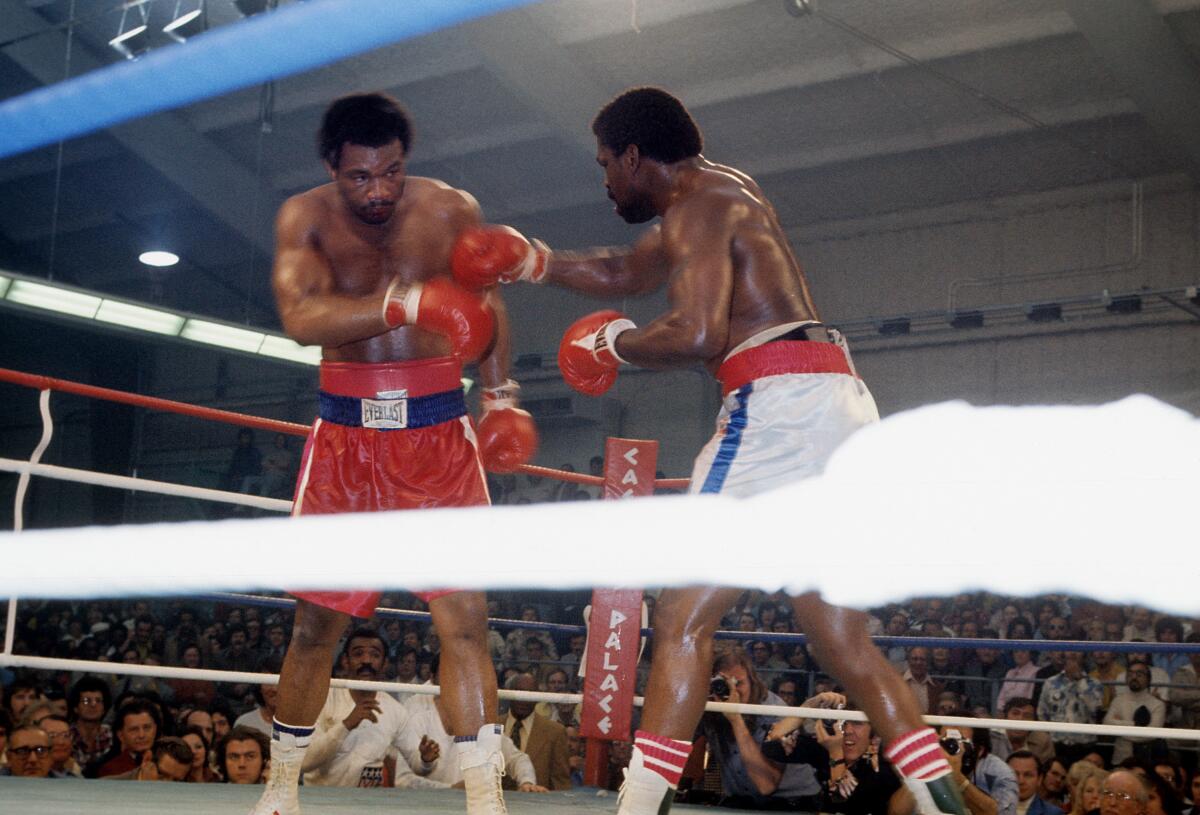

In 1976, Caesars Palace held one of its first major boxing shows, a slugfest between George Foreman and Ron Lyle that was named Ring Magazine’s fight of the year.

The unusually large sum of money gambled on the casino’s floor that night ensured Caesars Palace would remain in the fight game.

The casino erected temporary outdoor arenas for its major attractions. Ali, Mike Tyson, Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Thomas Hearns, Marvin Hagler, Julio Cesar Chavez and De La Hoya all fought there. In the 1993 rematch between Riddick Bowe and Evander Holyfield, a paraglider pilot crashed into the side of the ring in the seventh round.

Caesar‘s Palace’s role in boxing diminished in the 1990s, when the MGM Grand and its sister properties such as the Mandalay Bay started to host the majority of mega fights. Over the last three years, some major boxing matches have taken place in T-Mobile Arena, a joint venture between MGM Properties and the Anschutz Entertainment Group.

Both of Alvarez’s fights against Gennady Golovkin were staged in T-Mobile Arena, as was Mayweather’s lucrative but farcical novelty match against mixed martial artist Conor McGregor.

But the arena is home to the Golden Knights and also has a contract with Ultimate Fighting Championship. Boxing isn’t the only sports show in town.

“Those guaranteed ticket buys have disappeared,” Schaefer said, explaining why major fights are heading elsewhere.

However, the city still has advantages.

“Las Vegas’ infrastructure is such that there’s no other city in the world like this,” then-president of MGM Resorts Entertainment and Sports Richard Sturm told The Los Angeles Times in 2017.

Schaefer agreed. The fighters’ purses are a promoter’s greatest expense. Next are accommodations. Las Vegas properties can provide that.

Casinos are also able to stage open-to-the-public weigh-ins and various promotional events in the week leading up to a fight. The environment also allows promoters to charge more for tickets than other cities.

Before Alvarez’s first fight against Golovkin, promoter Oscar De La Hoya said he liked that he could also sell tens of thousands of tickets to closed-circuit viewing parties at the 10 MGM properties down the Strip.

Another perk: Nevada doesn’t have a state income tax.

And there’s the atmosphere. There’s nothing like a major fight in Las Vegas. No sport creates tension like boxing and no city helps build it up over a week of events like Las Vegas. By fight day, there’s usually a noticeable buzz on the streets and casino floors.

Boxing’s share of this singular market might be decreasing, but if the sport has a high enough profile, it still makes sense for it to end up there.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.