‘Nothing is making me quit’: How Cammi Granato earned her top spot in hockey

- Share via

Like her brothers, Cammi Granato loved playing mini-sticks hockey in the basement of the family’s suburban Chicago home. Inspired by the “Miracle on Ice” 1980 U.S. Olympic team, they’d pretend to be the upstart Americans who defeated the mighty Russians. Also like her brothers, she dreamed of making it to the NHL.

“I wanted to play for the Blackhawks, because those were my idols,” she says. “I dreamed the same dream as them and it didn’t occur to me until I was probably 12 or 13 years old, ‘Am I going to be able to do this?’

“My mom tried to steer me into another sport, thinking that at some point I’d have to quit, and I remember just looking at her and crying and ran up the stairs and saying, ‘I’m not quitting. Nothing is making me quit.’ … I was a hockey player. I lived and breathed it the identical way that my brothers did.”

Nearly 50 years after Congress passed Title IX, female athletes are still scrambling for a fair shot in the male-dominated world of sport. In hockey, top Americans and Canadians train with their national teams part-time; the rest of the season, they have only a small pro league that offers twice-a-week practices, weekend games and thin salaries.

Granato couldn’t play hockey at the University of Wisconsin, like her brothers Tony and Don, because there was no women’s team then. Instead, she played at Providence College as an undergrad and at Concordia University in Montreal as a graduate student. (Tony went on to have a respectable NHL career and Don is an assistant coach of the Buffalo Sabres.)

A clever forward with a great scoring touch, Granato played in the first women’s world championships in 1990 and was the captain of the champion 1998 U.S. team in the first women’s Olympic hockey tournament. After spending a season as a commentator on Kings radio broadcasts she returned to the U.S. team and won a silver medal at the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics. She played in nine world championship tournaments, highlighted by the American women winning their first world title in 2005.

In 2008, Granato became the first woman elected to the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame and was one of the first three women elected to the International Hockey Hall of Fame.

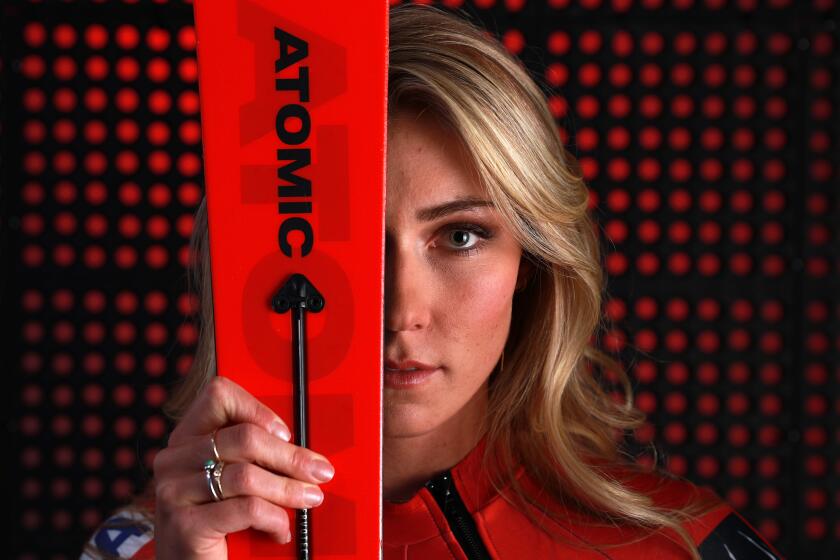

Two-time Olympic medalist Michelle Kwan serves as an inspiration to Alysa Liu and the next generation of figure skaters.

She recently recorded another first when she was hired as a pro scout by the NHL’s Seattle expansion team, a significant step in a wave of change that has included women being hired as NBA assistant coaches. “Women have been qualified for these jobs,” she says. “Now, it’s exciting because there’s people that are more forward-thinking that are offering these jobs and knowing the person is qualified, no matter the gender.”

Granato supported the women who vowed to boycott the 2017 world championships in Plymouth, Mich., if USA Hockey didn’t increase their pay and provide more programs for girls and women. Social media was an ally for them, a benefit Granato and her teammates didn’t have.

She recalled being hopeful that women’s hockey would boom after the 1998 team was welcomed home with parades and late-night talk show appearances, but her hopes fizzled when USA Hockey did nothing to promote them until the world championships were held in Minnesota in 2001.

“That’s the year that we tried to fight for some rights,” she said, “like the girls did two years ago, for the same things they were asking or very similar to things they were asking. … We were told basically, ‘Shut up and play,’ and [that] we were lucky to have a team.”

A settlement reached days before the 2017 world championships gave the U.S. women’s team better pay and per diem money and the same travel and insurance considerations as the men’s team. “I’m happy to know that change is here and that there’s momentum,” Granato says.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.