Column: The ‘Original Nine’ of women’s tennis made history — and a dollar each — 50 years ago

- Share via

Fifty years ago on Wednesday, holding a dollar bill and wearing smiles illuminated by more hope than certainty, nine women changed the course of professional sports.

Stymied by a system that relegated them to back courts and meager paydays while favoring their male counterparts, eight female tennis players joined influential World Tennis magazine publisher Gladys Heldman to form their own tour on Sept. 23, 1970. To play in the tournament Heldman organized in Houston, each became a contract pro by signing for $1. No one was sure how many additional dollars they would earn.

U.S. tennis officials warned them not to go out on their own. International tennis organizations said they’d be barred from Grand Slams. Kerry Melville Reid and Judy Tegart Dalton were banned by the federation in their native Australia. “We were ostracized by the other players,” Rosie Casals said. “It was, ‘What are you doing? You’re hurting women’s tennis. You’re hurting our chances.’”

They had everything and nothing to lose. The Open Era, which allowed pros and amateurs to compete in the same events, brought bigger earnings for men but not for women. Legendary player and promoter Jack Kramer had said prize money at the prestigious Pacific Southwest tournament in 1970 would be distributed to men in a 10-1 ratio and women would get nothing unless they reached the quarterfinals. That was common: Julie Heldman, Gladys’ daughter, got $800 for winning the 1969 Italian Open, then the fifth-largest tournament in the world.

Naomi Osaka earned her second U.S. Open crown and third Grand Slam title by beating Victoria Azarenka 1-6, 6-3, 6-3 and made a statement for the times.

On that day 50 years ago, they declared they wouldn’t be devalued anymore. “It was a risk. It was a gamble,” San Diego native Valerie Ziegenfuss said. “But at the time, there wasn’t much else. We just said, ‘Wow, this is not looking good, so if we don’t do something, who will?’ To now see what it’s become, it’s amazing.”

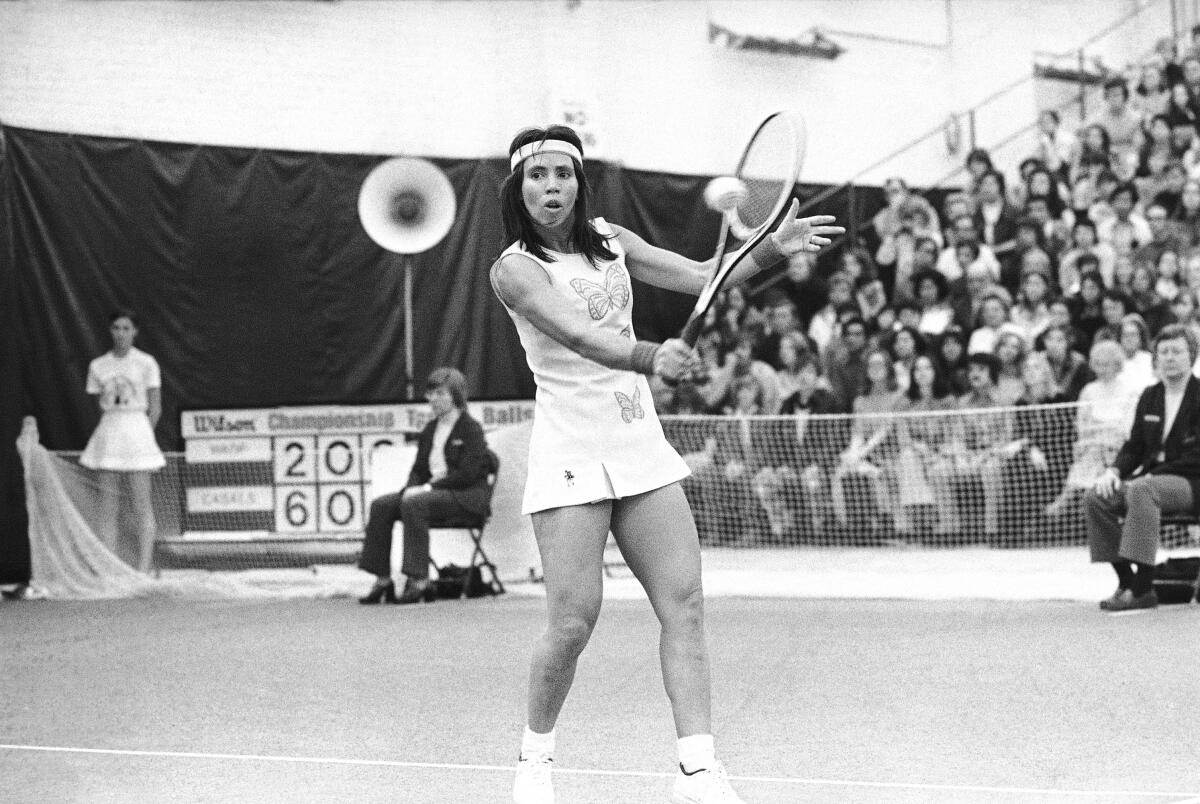

Casals, Ziegenfuss, Reid, Dalton, Billie Jean King, Peaches Bartkowicz, Kristy Pigeon, Nancy Richey and Julie Heldman are the Original Nine, pioneers whose efforts led to the rich payouts elite female tennis players now earn. (This year’s Australian Open singles winners each got about $2.9 million. The U.S. Open singles winners each got a pandemic-reduced $3 million.)

Gladys Heldman’s promotional savvy, King’s star power and the financial backing of Philip Morris chief executive Joe Cullman III made the launch of the Virginia Slims circuit possible, but King considers it as a team effort. “I think I got probably too much attention compared to them. I ended up being the spokesperson for all of us,” King said Tuesday during a phone interview. “The thing we had going was we could always laugh. We always had that common purpose we could go back to. We just had such a purpose and passion for it.”

Their timing was good, catching a wave as old assumptions and ideas were being questioned throughout society. “We were living through that period of time when everything was turned upside down,” Julie Heldman said, “but at the same time that a lot of things were changing, women’s place — certainly in sport — was simply nowhere. Everything really had to be manufactured from whole cloth.”

Casals won that first tournament. Heldman was injured but played one point, against King. “It felt incredibly important to stand by everybody, to stand up for what we believed in, stand up for the right to make money doing what we did best,” Heldman said.

Pigeon was the youngest of the group at 20. While studying at Mills College she had attended a lecture by Betty Friedan and was influenced by the simmering women’s rights movement. It was personal for her. “Growing up playing tennis I remember being harassed by kids for being a woman athlete. Also, my father was very unsupportive. His idea of a perfect woman was one who wore very high heels and tight angora sweaters,” she said by phone from Idaho, where she’s an animal and wildlife advocate.

“There was no decision for me to be made. I didn’t even think about it. I was on board from the very beginning, and I had a lot of confidence that Gladys Heldman could carry us forward to the next level and make things happen.”

Reid, a top-10 player for more than a decade and three-time Grand Slam singles and doubles winner, generally was shy but boldly joined the group. “It was mainly because of the other girls who were there in the beginning,” said Reid, who lives in South Carolina. “Someone like Billie Jean, who was No. 1 in the world back then was putting it all on the line, and Rosie and Judy Dalton, those players.”

Part of the job was doing clinics and interviews and appearing at cocktail parties between practices. “We spent more time promoting than we probably did playing,” King said. “We learned what we needed to make this happen because if the traditional media didn’t tell our story, we were nothing.”

Serena Williams hasn’t won a major tournament since 2017, but that hasn’t hindered her drive to win a 24th career Grand Slam title at the French Open.

Ziegenfuss recalled that time fondly. “We knew that nobody would be in the stands if we didn’t promote it and didn’t hand out tickets and didn’t reach out to the clubs and the tennis players at the time,” said Ziegenfuss, a realtor in San Diego. “So we really grew the sport, but the ulterior motive was we wanted people in the stands.”

Pigeon recalled accompanying Reid to an appearance at a Kmart during the first year. “We sat in the sporting goods section passing out autographs and trying to give people free tickets. Nobody really knew or cared who we were,” Pigeon said “There wasn’t a huge response so we had to work hard and say, ‘Hey, come over here, we want to tell you something.’ I can’t imagine today Serena Williams sitting in a Kmart.”

The tour gained more sponsors and grew. Chris Evert, Evonne Goolagong and other stars who had hesitated began to sign on. “I think by April of the first full year of the tour I got around $2,500 for getting to the semis of Las Vegas,” said Heldman, whose book “Driven: A Daughter’s Odyssey,” recaps the birth of the tour and her fractious relationship with her mother. “All the tournaments began to say, ‘This one is going to have more money than any others.’ Then there would be another one that would pay even more.”

Their profile zoomed thanks to King’s “Battle of the Sexes” match against Bobby Riggs in 1973, which transcended sports. “It put women’s tennis on the map,” said Casals, who lives in Palm Desert. “You were either for Bobby Riggs or you were for Billie Jean King, and women came out of the woodwork and took steps and said, ‘We don’t have to be just housewives. We can be career women or go into sports.’ It was a very important time.”

The quest for equal pay for female players continued for years. Among the Grand Slam events, the U.S. Open began offering men and women equal prize money in 1973; the Australian Open followed in 2001, followed by the French Open in 2006 and Wimbledon in 2007.

For Casals, the next quest is to get more women to promote and run sports and leagues. “You’re still living in a man’s world, you know,” she said. But what happened on that day 50 years ago made sports a woman’s world too. “If those nine women would not have taken that risk and stepped forward 50 years ago, we certainly would not be where we are,” she said.

They’ve come a long way from that $1 launch. “I’m not worried that other people are making a bazillion dollars and we didn’t. We did something important,” Julie Heldman said. “We took a stand when it was necessary and I think that probably all of the women players in our era — most of them, not all, for sure — would have done the same thing. We just so happened to be there at the right time and the right place. I’m thrilled that we could do that.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.