How a South Carolina lake helped forge Dustin Johnson’s Masters dreams

- Share via

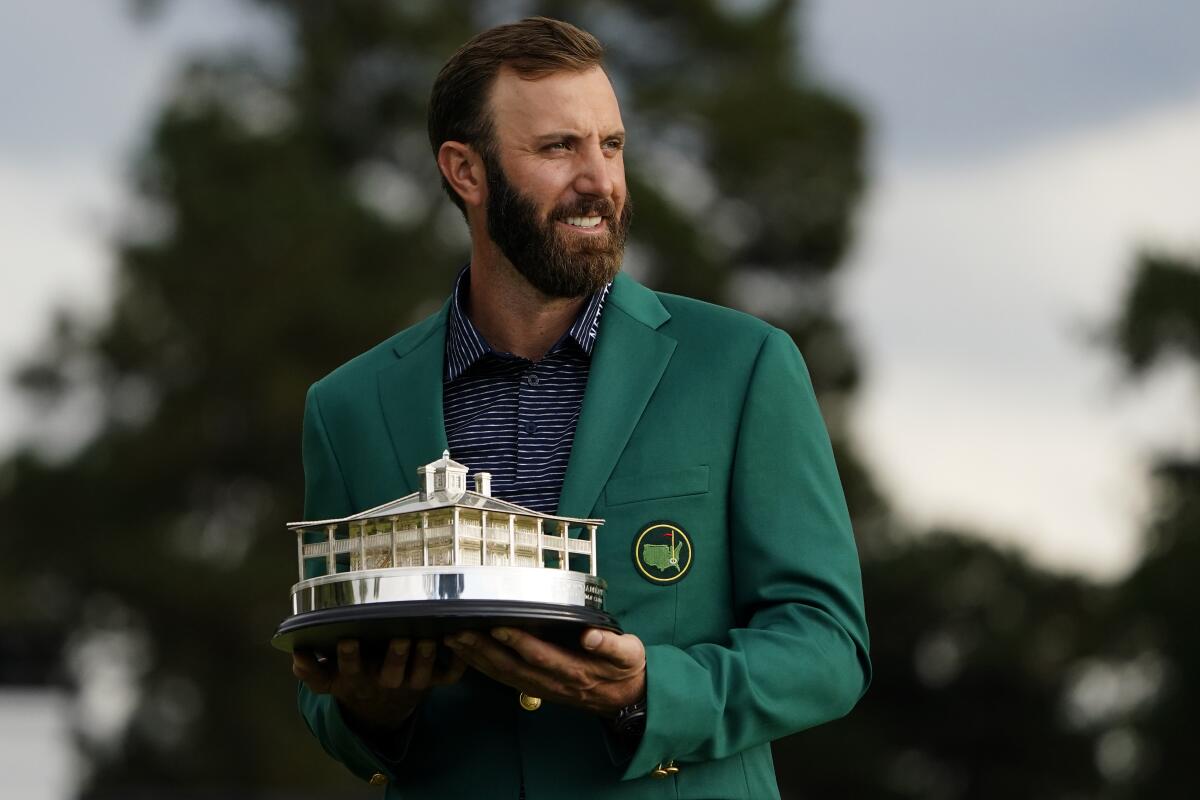

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Dustin Johnson won the Masters thousands of times before Tiger Woods helped him into that 42-long green jacket for all the world to see.

He won it from the front yard of his grandfather’s home on the northeast side of Lake Murray, with he and his kid brother — and future caddie — lashing buckets upon buckets of drives over and around neighboring houses and into the water.

Seven years ago, South Carolina Electric & Gas drew down the lake by almost 10 feet in an effort to improve the water quality. The muddy bottom exposed was layered with old golf balls.

“They found about 5,000 of them from Dustin and Austin,” said their grandfather, Art Whisnant. “They took range balls and they hit them out in the lake for 10, 12 years.”

The brothers would come to visit and rain down buckets of balatas.

“Neighbors weren’t too happy about that, but we were kids and would get bored,” Austin said. “Try to squeeze one between the houses.”

After tying the Masters scoring record through 54 holes, Dustin Johnson earned his maiden win at Augusta after becoming the first to finish at 20 under.

The brothers finally threaded the needle in a big way, with Dustin winning the Masters on Sunday at a record 20-under par for the tournament. He had held or shared the 54-hole lead in a major championship four previous times in his career, but this was the first time he was able to finish the job.

For the even-keeled Johnson, who had his brother on the bag, the win was highly emotional. He had dreamed of winning the Masters since his days of relentlessly practicing the game at the Weed Hill driving range, which is now an apartment complex.

“Obviously growing up in Columbia, in high school, I hit a lot of golf balls at Weed Hill,” he said. “So definitely remember hitting up there in the dark. They had lights on the range, and most nights I would shut the lights off when I was leaving.”

Wherever he went, Augusta National was always top of mind.

“Always around the putting green growing up, it was putts to win the Masters or hitting chip shots,” Johnson said. “It was always to win Augusta.”

Along the way, he won in plenty of other places. He lettered on the high school golf team as a tall, lanky seventh-grader. A friend of his grandfather’s brought him as a fill-in to a weekly money match he had with a group of buddies, and young Dustin, not yet old enough to drive, cleaned out their wallets. The fellow who brought him was told in no uncertain terms to never bring that kid back.

“He was really good at 10, 11, 12,” his grandfather recalled. “When he was in the seventh grade, he was setting a course record at a local place. They were having the high school banquet at the time, and they gave him the choice: He could either go to the banquet or stay there and break the record. He chose to stay.”

Above all, Johnson was supremely confident. According to a 2017 story by ESPN’s Ian O’Connor, Johnson had a geography teacher in middle school who asked him to identify a certain spot on a map.

“Mrs. Kennedy,” Johnson responded, “I don’t need to know where that is. When I’m on tour, I’ll get my pilot to fly my private jet where I need to go.”

His exploits are the stuff of local legend.

“When he was in college at Coastal Carolina, and the team stopped through Columbia to practice at Spring Valley,” his grandfather said, “on a par-three, he had a hole-in-one. And the next hole was a par-five, and he had a double-eagle.”

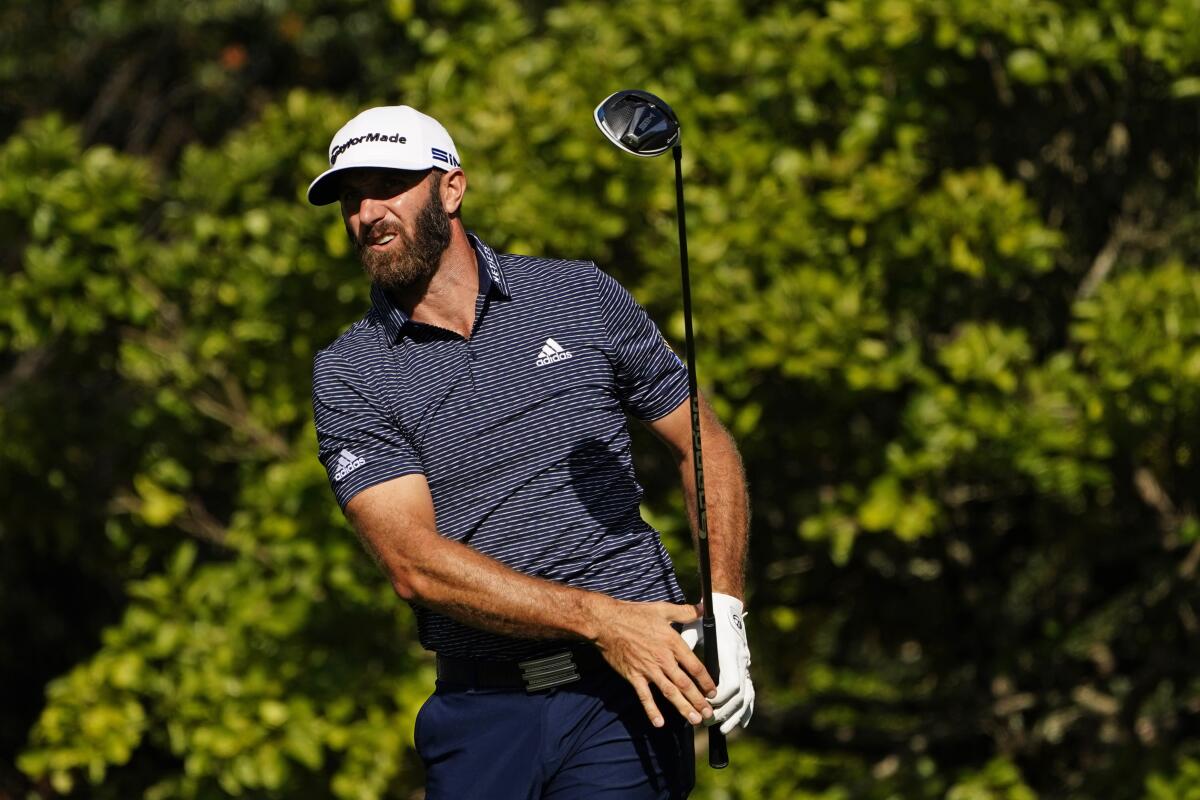

Then, there was the feat in 2018 at the Sentry Tournament of Champions at the Plantation Course in Kapalua, Hawaii. On the 430-yard, par-four 12th hole, Johnson crushed a drive that ran all the way to the green, tracked straight toward the pin, and stopped a few inches from the cup. It was a stunning shot.

One look at the 6-foot-4 Johnson and it’s no surprise he can stand flat-footed under a basketball hoop, leap straight up and dunk.

It runs in the family. Although at 6-4 he was smaller than almost everyone at his position, Whisnant was an All-ACC center at South Carolina from 1959-62, averaging 19.1 points during that span. He was a rebounding machine, and averaged more than 10 free throws per game. That was good enough to get him selected by the Lakers in the fifth round of the 1962 draft, although his NBA career never got off the ground.

Tiger Woods finishes with a 10 on the par-three 12th hole at Augusta National during the final round of the Masters on Sunday.

Whisnant wound up coaching youth travel teams around South Carolina and made a nominal effort to convince Dustin to play.

“He maybe played his freshman year,” Whisnant said. “He’d grab a rebound and he’d take it all the way. That’s how fast he’d get down the court. But he wanted to play golf.”

Austin gravitated to basketball, even though he too was good at golf, and went on to play guard for Charleston Southern.

The boys’ father, Scott Johnson, was an all-state receiver at Chapin High in Columbia who planned to play in college. He suffered a severe cut to his arm while working at a liquor distributorship, however, and the resulting tendon damage had him in a cast for more than a year. His football career was done, and he took up golf.

Jimmy Koosa, an accomplished golf pro in Columbia, was his instructor and worked first with Scott and years later with Dustin.

“Dustin would come when he was a little boy,” Koosa recalled. “He’d sit on the bag with me when I was teaching his dad.”

Johnson soaked it in, and started taking lessons himself. A few years passed, and that confidence bubbled to the surface.

“I remember taking Dustin to a pro junior when he was maybe 12 or 13,” Koosa said. “He hit a terrible shot off the first hole. He came over to me and said, ‘Jimmy, I won’t hit another one like that. I promise. I promise.’ Well, he really believes in himself. He believed he would never hit another bad shot. And he still believes that.”

At long last, Johnson has a green jacket to show for it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.