- Share via

On the night of the 2015 Southeastern Conference championship game — another Alabama victory that would catapult the Crimson Tide to the playoff and another national championship — the future of Georgia football was quietly coming into focus.

Super-agent Jimmy Sexton set the meeting for the Renaissance Hotel by the Atlanta airport. The time and location for Georgia athletic director Greg McGarity’s interview with Kirby Smart may have been a secret, but the fact the two parties seemed meant to be together was well-known.

McGarity felt like he already knew Smart, a proud Georgia graduate and Nick Saban’s co-pilot of the Alabama defense for seven seasons. He saw the way Smart carried himself after the 2012 SEC championship game, when the Tide handed the Bulldogs a heartbreaking defeat. Smart visited the Georgia locker room to share a moment with his close friend, Bulldogs offensive coordinator Mike Bobo — an image that stuck with McGarity.

But Georgia’s fifth-year athletic director hadn’t actually met Smart, and he probably had one shot to get this right.

Mike Leach was a college football visionary who’s impact extended beyond the playbook for TCU coach Sonny Dykes and offensive coordinator Garrett Riley.

After the game, as McGarity waited in the hotel room, a call came in from an unknown number. It was Saban, giving his approval for McGarity to speak with Smart. Saban’s only request was that Smart continue to coach his defense through the end of the season.

“Coach, we’re in it for the long haul,” McGarity told him. “We want you to go win a national championship.”

Of course, what Georgia really wanted was a ring of its own. It had been a long 35 years for the faithful, who had become more desperate by the year to collectively sing “Glory, Glory” on a Monday night in January.

Smart, a native of Bainbridge, Ga., wanted that, too. He’d coached on Mark Richt’s staff for one season before joining Saban with the Dolphins, and, once at ‘Bama, he’d observed his alma mater closely as a competitor on the recruiting trail and on the field. He knew the ‘Dawgs were close, and he believed he could push them over the top.

“It was a situation that I had prepared for for a long time,” Smart said. “But I don’t feel like the decision was going to hinge on an interview.”

After all, Georgia was family. And sure enough, once they were in the room together, with university President Jere Morehead, an easy familiarity filled the space. As a student, Smart took a business class taught by Morehead. Now, here was Smart in his early 40s, and Morehead was intent on convincing Smart the school would give him whatever he needed.

“He was interviewing us as much as we were interviewing him,” said McGarity, who retired from Georgia in 2020 and is now the head of the Gator Bowl.

Seven years later, as perfect as the marriage between Smart and Georgia appeared, it is still astonishing to see the formerly snake-bitten Bulldogs at the top of the sport and on the hunt for a second consecutive College Football Playoff championship. Starting with last season’s title game victory over Saban’s Tide and continuing with an undefeated championship defense, Georgia has unseated Alabama as the South’s most dominant program.

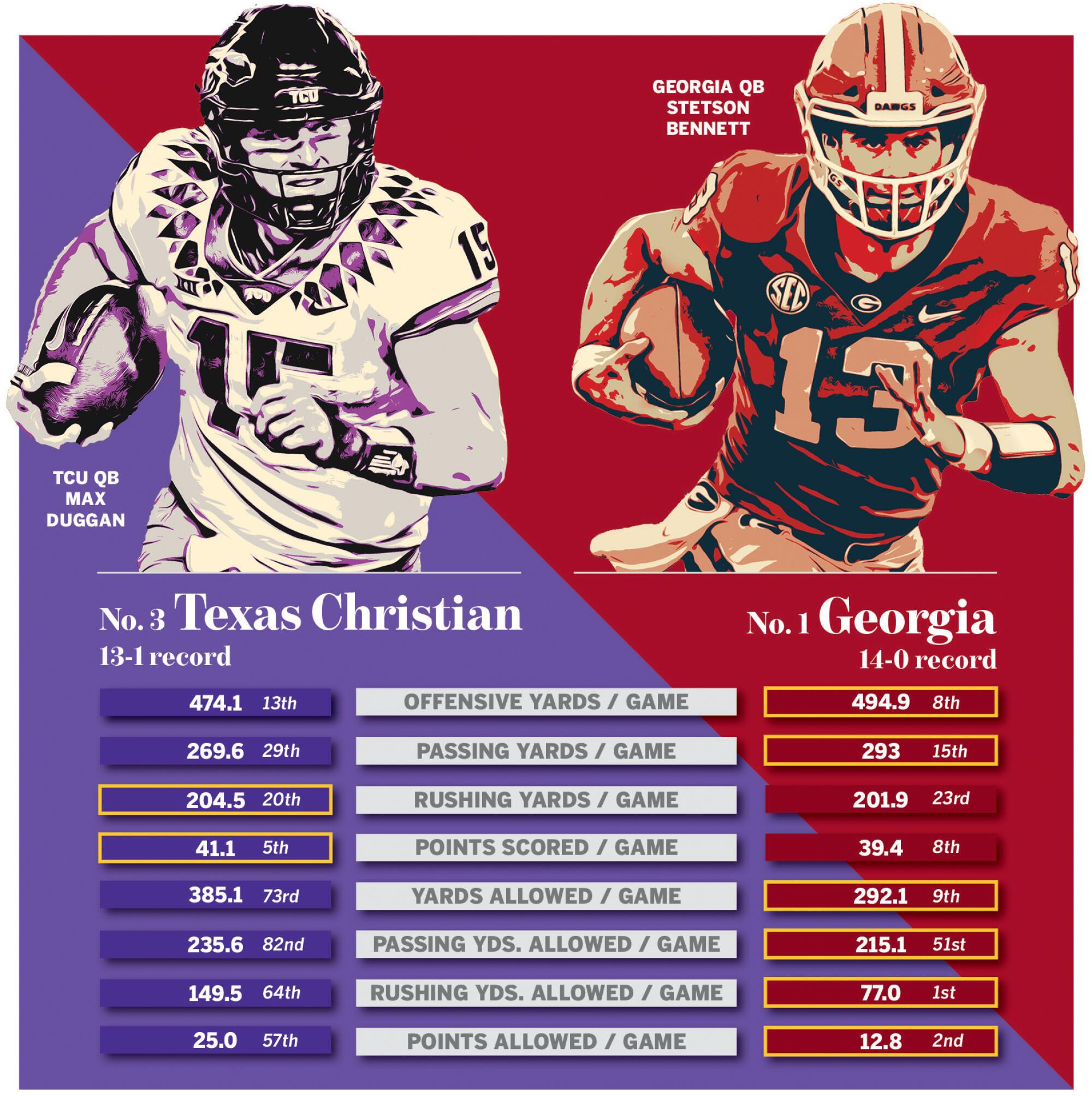

Monday night at SoFi Stadium, the Bulldogs are 13.5-point favorites over Texas Christian, the closest thing to a “Cinderella” story that modern college football has ever known. If Georgia does the expected and muscles past TCU, who would bet against the ‘Dawgs making it three in a row?

Saturday at CFP media day, Smart was asked what a movie about his Georgia program would be titled.

“Grit,” he said without hesitation.

Indeed, there has been nothing fancy about this remarkable rise, built on a tenacious defense that carried Smart until he built enough trust in his offense to finally unleash it. Even this repeat attempt was executed methodically, by believing in the culture that had been set years prior. While many of his peers were frantically mining the transfer portal during its initial foray into full-fledged free agency last offseason, Smart did not sign one transfer.

“We didn’t turn our nose up to the portal and not use it; we searched for a certain type of kid,” Smart explained. “If they don’t fit what we do, I don’t think we should bring them in. I’m a lot more worried about retention than I am going to get them. You know what I’m saying? I want to spend time investing in people in our program.”

Garrett Riley is the younger brother of USC football coach Lincoln Riley, but he created his own legacy long before he became TCU offensive coordinator.

Richt was not surprised when Smart emerged as his successor. It made too much sense to not happen, but even the most obvious hires often don’t pan out.

“If you had a poll back then of Georgia fans to predict who the next coach would be, it would be Kirby,” Richt said last week from his home a mile from the football facility in Athens, Ga. “But you know there’s been other hires that seem like the perfect guy, and it didn’t work out. So Kirby certainly did his part.”

Georgia’s journey since that fateful weekend in December 2015 carries with it plenty of lessons for other well-resourced programs out there who remain tortured — perhaps like the one nestled by downtown Los Angeles that made its own big-time head coaching hire one year ago.

“Georgia’s always had a commitment to football,” said Richt, who went 145-51 as the head coach from 2001-15. “But I think there’s a greater commitment since Kirby’s gotten to town, and a lot of it is due to his ability to let everybody know what’s needed and why it’s needed. And everybody bought in. You have your head coach, your athletic director and your president all on the same page, it allows really great things to happen.”

It was no accident that Lincoln Riley repeatedly used the word “alignment” in his introductory news conference at USC in November 2021. He wanted to make clear to everyone how important it was that President Carol Folt, athletic director Mike Bohn and himself not just began on the same page in the thrill of the moment but maintain the harmony.

There are distinct institutional and regional differences between Georgia and USC, but both schools have enough talent in their respective backyards to routinely recruit at a top-five level, and there is no doubt that the Trojans are among a handful of teams nationwide that can learn from the Bulldogs’ breakthrough.

The priority of working toward authentic alignment between school, athletic department and football team has been crucial for Georgia, just as it would be for USC going forward. There’s a reason that all season long after Trojans home games, Folt and Bohn were waiting to greet Riley and his family as they came off the Coliseum field.

Smart and Georgia achieved alignment quickly by little good-faith decisions that added up, like Smart including a talk with Morehead as a part of recruit official visits, or McGarity approving Smart’s requests for added staff members and the use of a helicopter to bypass Atlanta traffic during recruiting trips.

“Kirby’s time management was unparalleled,” McGarity said, “and to be able to hopscotch between multiple locations in a matter of minutes was important to him. It was kind of a no-brainer. Kirby didn’t ask for things just to ask for things. There was a purpose behind it.”

Early on, Smart gave McGarity a vision for a proper organizational flow chart. That was definitely inspired by Saban‘s mentorship.

“It was so large, coded with titles and salaries, and it helped me understand what it took,” McGarity said. “It was kind of hard to understand in the beginning, because you didn’t know what all these people did, but after seeing it play out, you understood, ‘OK, this all makes sense.’”

Smart’s turnaround didn’t begin with a flourish like Riley’s first season at USC. In 2016, the Bulldogs lost 45-14 to Mississippi, dropped all three rivalry games to Tennessee, Florida and Georgia Tech and — gasp — fell to Vanderbilt in Athens. They finished 8-5 thanks to a Liberty Bowl win over, coincidentally, TCU.

But year two started with an emphatic statement — a 20-19 win at Notre Dame, where Georgia had never played before.

“Georgia fans literally took over the stadium,” McGarity said, “and to win that game, I think, just gave everyone a new level of hope.”

That 2017 season, Georgia won the SEC and outlasted Riley’s Oklahoma team in the Rose Bowl before losing in overtime to Alabama in the CFP title game.

In 2021, it felt like more of the same, with Georgia going 12-0 but losing to Alabama in the SEC title game. But the Bulldogs’ body of work got them into the playoff, where they walloped Michigan on the way to slaying the Saban dragon during a 33-18 victory.

That Kirby Smart, the son of longtime Bainbridge (Ga.) High football coach Sonny Smart, returned the Bulldogs to glory for the first time since 1980 felt just right.

Matt Groening is thrilled Hypnotoad, the mind-controlling frog featured on the TV series “Futurama,” helped fuel the TCU Horned Frogs’ CFP run.

“There’s one reason for where we are, and that’s Kirby Smart,” said Loran Smith, 84, a Georgia football historian who is writing a book with Smart about last year’s title run. “It’s hard to win a championship. Everything has to break just right for you. But if you come to practice and you watch Kirby work, I mean, there is not one wasted second. He has indefatigable energy.”

Smart revealed Saturday that Sonny and his mother, Sharon, won’t be making the trip to L.A. due to some recent health issues for his dad.

But Smith and Bulldog Nation will arrive at SoFi Stadium riding high after a stirring, 42-41 comeback win over Ohio State, which held two 14-point leads in the Peach Bowl. Winning one like that for once truly showed how far Georgia has come.

“It’s just absolutely the greatest,” Smith said. “I think we’ve always been seeing Alabama win games like we won against Ohio State, and I’ve felt, ‘Saban’s a lucky son of a gun.’ Now we’re the lucky sons of guns, and I love it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.