- Share via

The guys who crown the next big thing at the most glamorous position in sports take their job quite seriously. To them, their annual Elite 11 final competition isn’t just some camp where there’s a trophy given or an MVP title bestowed at the end.

“It’s ‘American Idol’ for high school quarterbacks,” says Yogi Roth, a Pac-12 Network analyst and former USC quarterbacks coach who works the event.

But even the organizers of the event will tell you — and this was certainly the case in summer 2019 — that a pecking order exists entering the weekend. It’s inevitable, a product of human nature, really. By the end of their junior years, most of the young men being considered for those coveted 20 spots have been scrutinized in such minute detail between their high school and 7-on-7 performances that it can feel like there isn’t that much new to see.

When Bryce Young arrived at the Los Angeles regional that spring, it was a foregone conclusion he would receive an invite to the finals in the Dallas area. Young, a consensus five-star recruit then committed to USC, had attended his first Elite 11 camp three years earlier while he was an eighth grader.

“We snuck him in,” Elite 11 director Brian Stumpf says. “We really don’t do a ton of young guys, especially that young. He’s always been that guy in terms of just cool, calm, collected.”

“Steph Curry with a football,” Roth says.

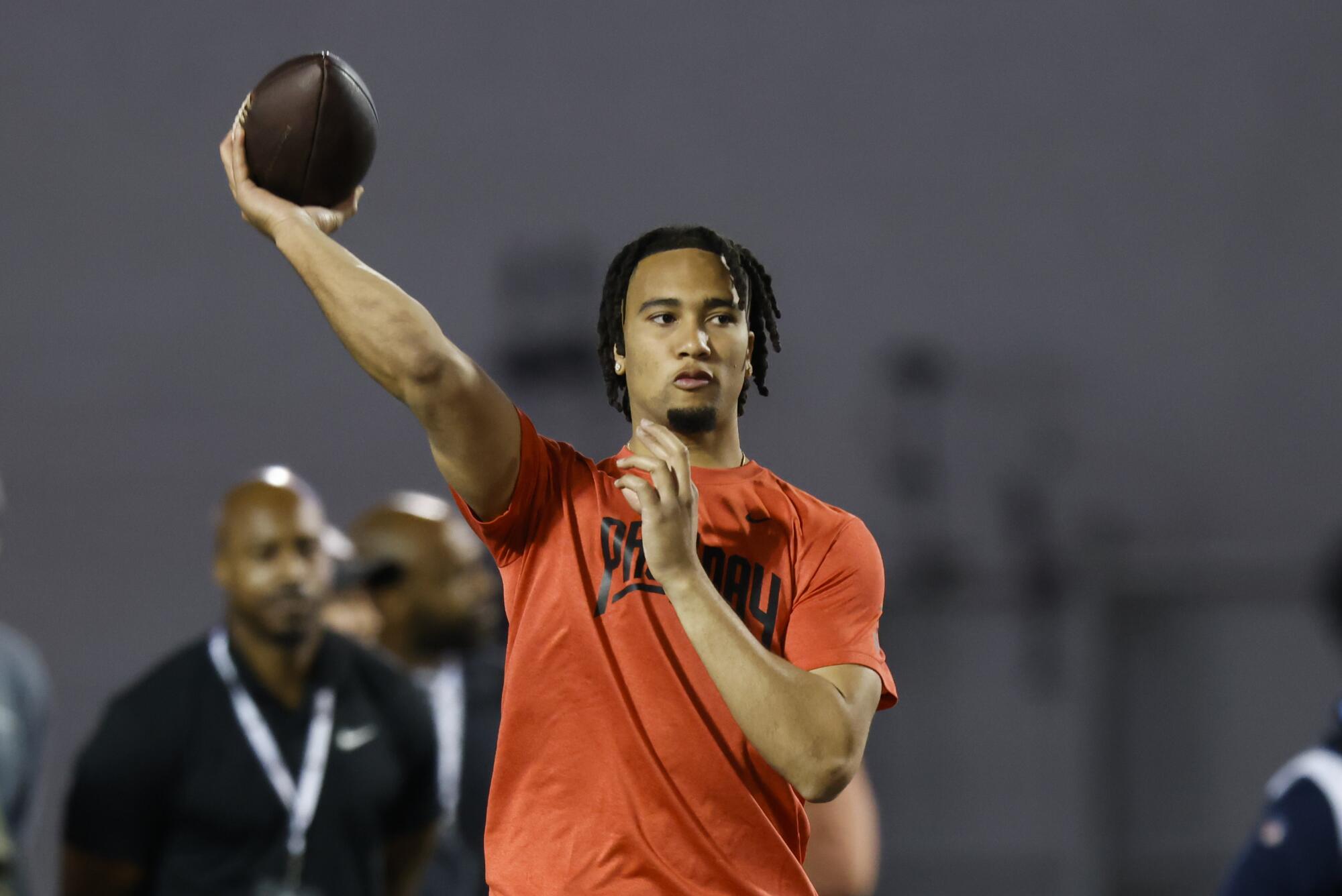

The L.A. regional was the first Elite 11 audition for CJ Stroud, who had shown promise during his first year as a starter that fall at Rancho Cucamonga High. He stepped on the field that day with a three-star ranking and a couple of lower Pac-12 offers, hoping this would be his moment to prove he belonged at the finals. Stroud played well, but he did not dazzle enough to receive an invite to Dallas. He was told to stay hungry and come out to the Bay Area regional later in the spring.

Nearly four years later, after months of Young and Stroud being poked and prodded and pitted against one another as potential No. 1 overall picks in Thursday night’s NFL draft, it is hard to believe just how much ground Stroud has made up since their high school days in Southern California. This is the story of the key stretch of weeks when Stroud began his rapid ascent into Young’s orbit.

Stepping back into Stroud’s 2019 reality, time was running out for him to grab the spotlight. So Stroud and his mother, Kimberly, cobbled together the money to make the trek to the Bay Area. They decided they would combine the event with a visit to Berkeley, since California was one of the schools interested in CJ.

Alabama’s Bryce Young, Ohio State’s C.J. Stroud, Florida’s Anthony Richardson, Kentucky’s Will Levis are top QB prospects in NFL draft, but where they go is a mystery.

Kimberly was so proud of her youngest of four for putting himself in this position after everything they’d endured the last few years, with CJ’s father freshly out of the picture. Coleridge Stroud was serving a 38-year sentence at Folsom State Prison, having pleaded guilty to charges of kidnapping, robbery and carjacking while CJ was still in middle school.

In the years that followed, CJ’s football dream kept his heart pumping, even as he struggled to win the starting job at a public high school that could not have been farther away within L.A.’s prep football landscape that featured epic battles between Young’s Mater Dei and fellow five-star DJ Uiagalelei’s St. John Bosco juggernauts.

The Strouds lived in a small apartment above the Upland storage facility where Kimberly worked. They did not have the funds for a personal quarterback coach or to attend showcases. But that did not stop CJ.

“CJ always found a way to get someone to waive something, find him sponsors,” Kimberly says. “He would make sure they could do that before he would even sign up for the camp.”

At the Bay Area regional, CJ continued to perform at a high level in front of the Elite 11 kingmakers. But, while Southern California peers Uiagalelei and Ethan Garbers received their finals invites, Stroud was told he would have to wait to find out his fate until the evaluators finished one more regional the next week in Nashville.

“After every camp, we were a little discouraged, especially when we went up north,” Kimberly says. “He thought he was the best, and they still didn’t invite him. I think that just really put a chip on his shoulder.”

CJ wasn’t going to just sit around waiting for good news. He kept in touch with Stumpf, trying to stay top of mind. And one day at the storage facility in Upland, Stroud’s phone buzzed.

Turned out, it was his future calling. He was an Elite 11 finalist.

Live on FaceTime with the organizers, Stroud went to find his mom, who was busy showing a customer a storage unit.

“‘Mom, they invited me, they invited me!’” Kimberly remembers him saying.

“We were just hugging each other and crying,” she says. “He just knew his luck was going to change.”

A few days later, Kimberly dropped off CJ at the airport. More tears. More prayers. Her boy was off to Texas.

“After he was invited, he walked off the tarmac into Dallas with a little bit of a different mentality,” Roth says. “He knew he was an unknown, and he knew what that stage could be.”

Recalls Stumpf, “You could tell he was singularly focused on showing everybody who he was. He’s the only guy we’ve ever seen still throwing on the field when practice is over, talking wide receivers into staying with him. We literally had to turn off the lights to get him off the field.”

For the interested public, most of which are college football fans watching their future quarterbacks, the focus of the Elite 11 finals is on the final rankings and potential bragging rights — which of the 20 competitors makes the cut to 11 and which passer is named the MVP.

But for the Elite 11 organizers, which included former Super Bowl-winning quarterback Trent Dilfer, the goal is to spend the four-day weekend imparting deeper knowledge that will help the players transition more easily into college football.

In 2019, their focus was on “emotional intelligence.” They wanted to create an environment in which the players would have to compete with one another but also be honest and respectful in their evaluation of their peers. They separated the players into four pods of five, and those groups would do everything together, just as a college team’s quarterbacks do. They would also vote on one another throughout the process.

By coincidence, Young and Stroud were placed into the same pod. Stumpf says they wanted the pods to be as equal as possible, and Young was viewed as the top player, with Stroud more in the 10-to-15 range.

Since they were on the same team, if Stroud was going to show coaches around the country what he could do in the 7-on-7 portion of the event, he would have to take snaps from Young, the assumed front-runner for Elite 11 MVP.

Stroud had watched Young’s star brighten from the time they were kids playing in the same youth football and basketball leagues. To him, Bryce was just Bryce, the kid who seemingly had everything he didn’t — the devoted two-parent home, the private-school pedigree, the personal quarterback coaches and the five-star hype machine following his every move — but somehow remained humble and relatable.

CJ’s father couldn’t be there for him like Bryce’s dad, Craig Young, was every day, but Coleridge Stroud did leave his son with one piece of wisdom that was helpful that weekend. A minister in the years before his arrest, Coleridge would often tell CJ that “comparison is the thief of joy.”

“CJ is very adamant not to compare himself to anyone in the aspect of competition,” Kimberly says. “He got that from his father, who had a lot of sayings and expressions. Never compare yourself to anyone. You start doing that, you lessen your thoughts of yourself.”

To start the 7-on-7 tournament, all the quarterbacks got their shot to lead their teams. As the event wore on, observers were surprised to see Stroud continuing to take snaps while Young looked on from the sidelines.

“CJ had the hot hand,” recalls Craig Young, Bryce’s father. “The coach kept him in there.”

At the end of the weekend, after Stroud led their team to the championship, his peers voted him Elite 11 MVP.

“CJ and Bryce ended up one and two, but unfortunately we put them on the same team, and as it got to the last day, there were really only reps to go around for one of them,” Stumpf says.

“It speaks to who Bryce is as a person and teammate, being able to absorb that. He definitely wasn’t kicking his dog or complaining to the coaches. Also, he liked and respected CJ and saw him blossoming, and it was really good for him.”

So good that coaches from programs such as Ohio State, Georgia and Oregon began blowing up CJ’s phone and texting Kimberly, who was watching it all unfold in Upland.

“Somehow, everyone finds your number,” she says, laughing.

Later that fall, of course, Stroud committed to the Buckeyes. By that time, Young switched his commitment from USC to Alabama.

Two years later, in 2021, they’d share the stage at the Heisman Trophy ceremony in New York, where Stroud cheered for the victorious Young just as Young had backed him that weekend in Texas.

The 2023 NFL draft appears top heavy with quarterbacks. Sam Farmer makes his predictions and picks for Nos. 1-31 in his final mock draft. Round 1 is Thursday.

“They’re like brothers now, but that was the genesis,” Craig Young says, “spending that time together in their pod and bonding.”

With NFL draft night finally here, Stroud won’t have much trouble keeping perspective about wherever he lands. He’s already traveled so far. With the endorsement money he earned at Ohio State, he was able to pay for Kimberly and his older sister, Cieara, to move out of the storage facility and into a fully furnished home.

“Everything in this whole journey has been slow, then quick, then super quick. There’s not a medium mode,” Kimberly says.

No matter what happens from this point on, the Strouds will never forget the pure relief and elation of those weeks in 2019 when the quarterback’s career first kicked into high gear.

“CJ always said if you stay ready, then you don’t have to get ready,” Kimberly says. “All he needed was a chance.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.