- Share via

GAYAZA, Uganda — Paul Wafula found Dennis Kasumba in a slaughterhouse.

By the time he was 14, hunger and hopelessness had led Kasumba to drop out of school and take a job slaughtering cows, sheep and goats. It was a Dickensian environment, one in which the workers, mostly young boys, were bathed in blood.

Wafula remembered of the pair’s first conversation: “I asked him why he was working in the slaughterhouse and he was like, ‘I want to have something to eat. We don’t have anything to eat at home.’”

So Wafula, a volunteer baseball coach, made the boy a deal: leave the slaughterhouse and each time he came to the baseball field he would be fed. When Kasumba became a regular, Wafula sweetened the deal: If he kept coming, the coach also would pay for him to go back to school.

And so began a relationship that would confirm Wafula’s belief in the redemptive power of the sport and fill Kasumba, now 18, with dreams of becoming Uganda’s first major leaguer.

Kasumba never knew his parents. His father, a soldier, went off to fight anti-government rebels in Uganda’s civil war and never returned. So his mother abandoned her 2-month-old son and two elder siblings on her mother’s doorstep and fled.

In Uganda, nearly 2.5 million children — one of every nine — is an orphan. For many, poverty and despair hang over them like a toxic cloud.

More than half a dozen of the boys and girls on Wafula’s sandlot team are orphans, which is why the coach uses baseball as a tool to teach larger lessons.

“I want to show them that the biggest challenge you’re facing in life doesn’t mean that your life has ended,” he said. “I know how it feels at that age. When I was younger there were times I went without a meal. I know what it forces you to do.”

So when Wafula persuaded Kasumba to leave the slaughterhouse, the goal wasn’t just to give Kasumba something to fill his stomach and his mind. It was to give him hope too.

“If you don’t have hope, why do you even get up in the morning?” Wafula asked. “If you don’t have hope, you don’t have anything.”

Four years later, that hope feeds Kasumba’s big league dream, a Quixotic one in a country where only 2,500 people are estimated to be playing the game and on a continent that has produced just two major leaguers, both South Africans who combined to appear in 62 games between 2017 and 2022.

“If I work hard,” Kasumba said in a voice barely above a whisper, “I think I can.”

Wafula and Kasumba are an odd couple, one formed by necessity and forged with determination. For the coach — perpetually upbeat, his default expression a warm gap-toothed smile — Kasumba is proof that Uganda’s oft-forgotten orphans can aspire to more than a desperate existence in a slaughterhouse. For the player, who is often stoic and quiet, already worn down by his life experiences, Wafula feeds those aspirations from a bottomless well of encouragement, inspiration and faith.

Wafula, who at 28 is just 10 years older than Kasumba, is more life coach than baseball coach, one who speaks in affirmations and believes deeply that sport can change lives, because it changed his.

He grew up sharing a one-room house with seven family members in a slum so notorious it has since been demolished. Like most children in Uganda, he played soccer before changing to baseball, starring for the Uganda national team after playing five seasons as a pitcher and outfielder with an independent league team in Japan.

Yet it’s his failures more than his successes that inform the lessons he teaches his players.

“I was once living in the ghetto. I don’t want the same situation to happen to these kids because when they have nothing to occupy themselves, they have different groups to join,” he said, referring to neighborhood gangs.

Wafula’s classroom is a bumpy field owned by a local church in Gayaza, a dusty, crowded crossroads about 15 miles from the center of Kampala, Uganda’s capital. There is an uneven dirt infield, two dugouts, a tiered concrete grandstand behind a flimsy wire backstop, and just the hint of a pitcher’s mound. Herds of cows and fearsome-looking long-horned Ankole cattle make frequent trips through the outfield looking for places to graze — and leaving behind cow pies that make diving catches treacherous.

Dennis Kasumba helps a disabled child hit a ball at St. Lilian Jubilee Home in Guyaza, Uganda. Some of the players, along with their coach, travel to the church-run home for disabled and disadvantaged children at least once a week.

Still, several boys and girls show up regularly, many of them barefoot, to play a sport that has drawn their attention because it is so rare in Uganda. But they really come to bask in the one thing they get from Wafula they can find nowhere else: attention and love.

“That’s it! Nice try!” he shouts to a young girl who has missed a ground ball.

“Strong throw! Strong throw!” he says to a boy whose toss from shortstop sails over the first baseman’s head.

Uganda’s massive orphan population was fueled primarily by respiratory disease and HIV/AIDS, which accounted for nearly a quarter of all deaths in the country as recently as 2018. But there are also tens of thousands of orphans who were just abandoned.

Together, Wafula and another coach, Ssempa Johnbosco, are caring for several children who are missing parents, giving them shelter and a baseball, the tools Wafula used to escape poverty.

Some of those children are grown now, such as Allan Kabenge, who throws a fastball that touches the low 90s. He has played for the Ugandan national team and briefly in Japan.

“Baseball is the only thing that saved my life,” said Kabenge, who lives with three other players in a one-room concrete house rented by Wafula. “Baseball is my family and the players are my brothers.”

Those brothers include Ibrahim Bukenya, 15, who, along with the grandmother he cares for, is homeless; Rymond Kasasa, 17, a refugee who lost his parents to the genocide in neighboring Rwanda; and 10-year-old Johnatha Osinde, who was abandoned by his mother and now lives with Johnbosco.

“That’s probably the biggest driving force of why people get into baseball within Uganda,” said Tom Gillespie, a scout with the Pittsburgh Pirates, the team that signed the first African to reach the major leagues. “A lot of the reasons that coaches were driven to work with the kids was to keep them off the streets. And a lot of the reasons that kids stuck with baseball was because they knew the alternative wasn’t good. It gave them that sense of community.

“Especially because of the high orphan rates in Uganda and the extreme poverty.”

Kasumba, too, sees baseball as a way out of that poverty, for him and the grandmother who took him in when his mother fled.

“The reason I’m working so hard is so that I can buy a big house for my grandmother,” he said.

Kasumba and his grandmother share a tiny brick-and-stucco house with seven others. Hidden down a narrow, rutted dirt road, the house has a concrete floor and no furniture or running water.

A single, bare light bulb dangles from a cord in the center of each of the house’s three rooms and the air is thick with stench from the cow pens less than 50 yards from the front door.

This is the reality Kasumba hopes to escape through baseball.

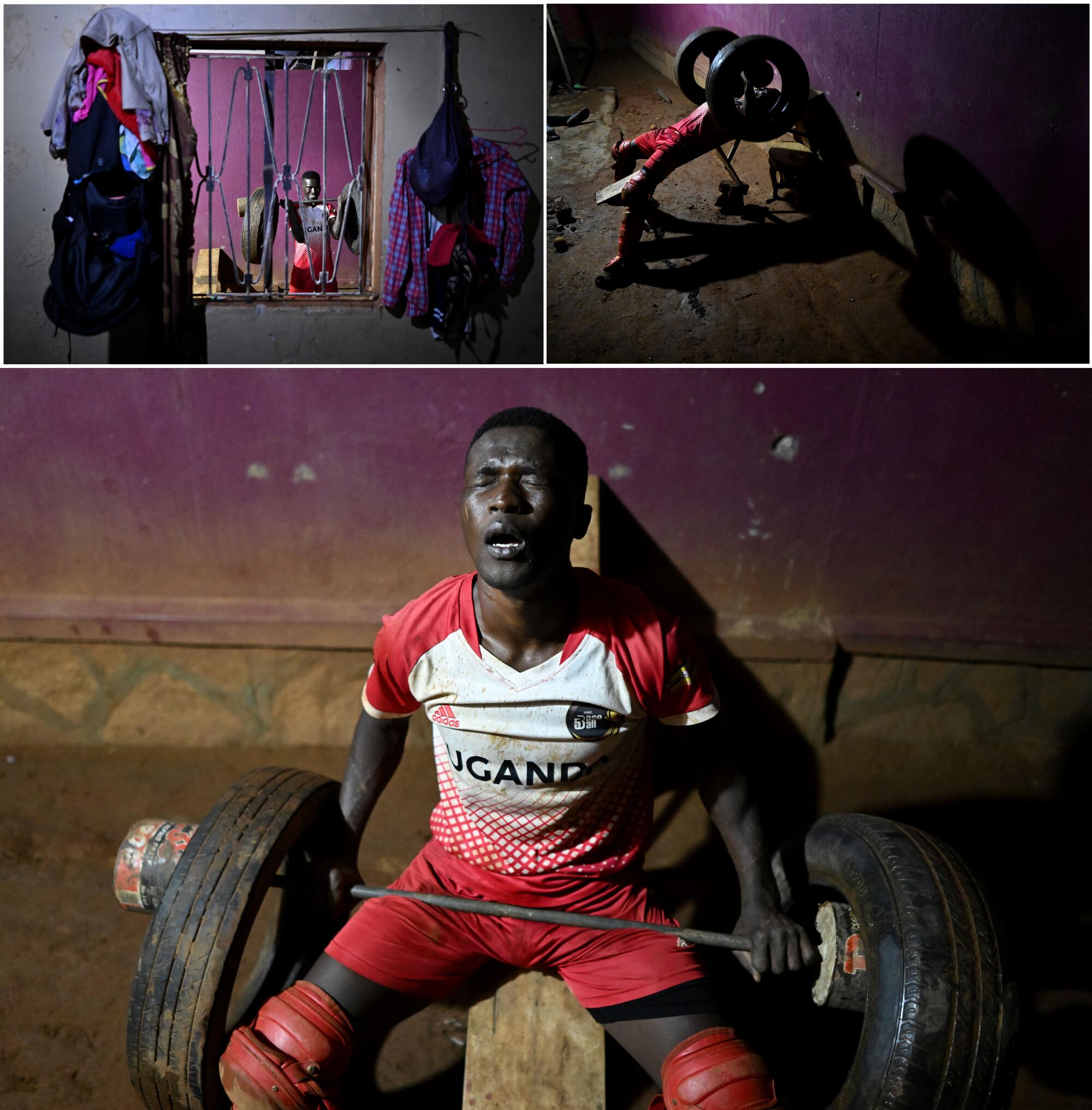

So each morning, he pushes himself off a thin mattress just as the sun begins to peak over the horizon. The day will unfold just as the last one did and the one to follow: Kasumba will step into the muddy path in front of the house and perform a dizzying array of drills using, among other things, a stack of old tires, plastic bottles filled with water and a weathered blue backpack stuffed with rocks.

Wafula shows up about an hour into the workout and stands in mud and watches, sometimes calling out encouragement in English or Luganda, the Bantu language preferred in central Uganda.

“That’s it! That’s it,” the coach shouts, toggling between languages, often in the middle of a sentence. At other times he will step in and correct Kasumba’s posture or positioning to make sure the exercises work the right muscle groups.

“In Africa,” Wafula said later, “if you want to be better, you have to work harder.”

For two hours Kasumba will lift, jump, twist and punch in the rain or in draining humidity. But if only his coach sees that, did it really happen? Does anyone know how hard he’s working?

So a cousin, Esther Nassali, films Kasumba on a cellphone the family received as a gift, then posts the videos beneath inspirational messages on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, where they have drawn tens of thousands of followers. The unique workouts even earned him a two-minute segment on South Korean TV.

Dennis Kasumba jumps inside a 55-gallon drum filled with water to strengthen his legs during a workout outside his home.

“We have been getting attention from all over the world,” Wafula said. “He can’t afford a gym, so he has to improvise.”

One of the people who saw the videos is Joshua Williams, an Atlanta attorney with Taylor English Duma who has started a campaign to bring Kasumba to the United States. Williams recently secured an invitation for Kasumba to play in the MLB Draft League, an amateur summer league that opens June 1, if he can get a visa.

Two previous visa requests ended in disappointment with the U.S. Embassy rejecting the applications, ruling that Kasumba had insufficient family ties that would draw him back to Uganda.

It’s hard to prove family ties when you’re an orphan.

In the evening, dressed in thread-bear red shorts and a red-and-white Uganda national team jersey with a large black No. 9 on the back, the same outfit he has worn all week, Kasumba does a second two-hour workout with a catcher’s glove so full of holes it’s held together with twine. Next to a concrete-block outhouse, he whacks balls off a tee using a crude bat fashioned from a tree branch.

With Wafula again watching and encouraging, Nassali recorded all of that too, with the videos highlighting Kasumba’s will, determination and creativity more than his talent.

In between workouts, he walked through the mud and puddles to a rickety cow pen and stepped barefoot into the mix of mud, manure and urine, mucking the stall in exchange for 4,000 Ugandan shillings, about $1.06. That will cover his food this day. Earlier in the morning, he fed the same cow to make a few cents to buy sugar for his grandmother’s tea.

“I’m working hard because I have an aim to become an MLB player,” Kasumba said.

He’s facing incredibly long odds. Not only has no Ugandan played in the majors, no one from his country had even played minor league baseball until last year when the Dodgers signed Ben Serunkuma, a 21-year-old relief pitcher, and Umar Male, a 21-year-old outfielder. This winter Gillespie and the Pirates signed pitcher David Matoma, a 17-year-old right-hander.

Dennis Kasumba catches warmup pitches at National field in Guyaza, Uganda. Most of the players that play on the field are orphaned, including Kasumba.

Then there’s Kasumba’s size, which is more suited to a soccer midfielder than to a catcher. Kasumba can reach 5 feet 7 if he stretches his spindly legs and stands on his tippy-toes. And he might weigh 150 pounds when he climbs, soaking wet, from the water-filled barrel he uses in his workouts.

Heart, however, seemingly accounts for half that body weight.

“That boy is committed. He knows what he wants,” said Roderick Ahimbazwe, a Ugandan photojournalist who follows the country’s baseball closely. “The only problem is he was born on the wrong continent.”

For Wafula, he has seen the transformative power of baseball in action, not just with Kasumba but at the church-run home for disabled and disadvantaged children he and his team visit every week, both to lift up the kids there but also to let his players know that whatever hardships they’re facing, it could be worse.

“When I go to visit the disabled kids, I want all [my players] to travel with me and show the same love I show to them,” said Wafula, who said an older brother has been confined to a wheelchair since breaking his spine in a car accident 15 years ago. “These kids also want to be shown love, but they don’t have anyone.”

These are the orphans nobody wanted: children, some still in diapers, who are blind, missing a limb, unable to walk or dealing with a mental disability. It’s a sad place, one where the children sleep as many as three to a mattress in a stuffy room lined with bunk beds.

Wafula, tall and well-built like the hard-throwing right-handed pitcher he once was, made it through secondary school and into college — a rare feat in a country where only one in four students attend high school — before dropping out because of the high costs. But what he lacks in book learning he has more than made up for in wisdom, humanity and street smarts.

The program he has taken to the orphanage is one he borrowed from Miracle League, a Georgia-based group that uses baseball to help children with mental and physical disabilities make friends and become confident. So Wafula’s players toss them plastic balls or string together plastic water bottles to fashion a bat for children too weak to hold a real one.

Kasumba was in the middle of the action, carefully molding a bat for a child in a wheelchair, then gently tossing a ball his way. When the ball was slapped back his way, he cheered. But more important, his stoic demeanor faded and he broke into a rare smile, making it hard to know who is really getting the most out of the exercise.

“They have a great thing going in Uganda,” said Stephanie Davis, the vice president of national programs for Miracle League. “It may look different than our typical Miracle League because of resources, but the concept is the same: motivating them to realize if they can play baseball, they can do anything.”

Speaking of the future, Wafula isn’t sure how he will keep going. Finding homes for orphans, stoking Quixotic big league fantasies and bringing hope to the otherwise hopeless can be exhausting, both mentally and emotionally.

“Sometimes I feel like enough is enough,” he said sadly, sitting behind the makeshift backstop before the start of a Saturday afternoon all-star game. “I get to a point when I have nothing to provide.”

Plus his wife, Barbra, and their twin children, a boy and a girl, say they are being ignored.

“You know how people get drunk on something?” Wafula finally said with a smile. “My wife says I’m drunk on baseball.”

What drives him are the kids. If he gives up, who will pull them out of the slaughterhouse?

“This is their only hope,” he said, gesturing toward the dusty field.

Still, he wonders, what’s the point of getting one barefoot orphan off the street if he’s only going to be replaced by another? What’s the point of encouraging Kasumba’s impossible dream if the odds are it will end in failure?

The point is that not doing anything would be even worse. Just as in baseball, it’s far better to try and lose than to not have played the game at all.

So when the coach talks about developing players, he really means developing people. If the orphans on his team never play on a bigger stage than the ragged field in Gayaza, at least they have a zinc roof over their heads, some food in their stomachs and someone who cares about them.

And if Kasumba never makes it to the U.S., much less the major leagues, all that work will not have been in vain. He has learned about discipline, compassion and dedication while building an international fan base through social media.

“When I met Coach Paul, my situation was very, very bad. He kept me in baseball,” Kasumba said of the man who has become the father he never had.

Edith Nantenze, the grandmother who nurtured him, agreed.

“I thank Coach Paul,” she said. “Coach Paul has done very great work.”

Kasumba is an orphan, but he couldn’t ask for better parents. Still, he has a dream to chase and he’s not going to catch it by slacking off.

So as his coach and grandmother visit, Kasumba places a 55-gallon drum on a tire and fills it with water. After climbing in, he wraps two thin elastic chords over his shoulders for resistance then begins leaping out of the drum, drawing his knees toward his chest. Nearby, his cousin lifts her phone and presses record.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.