Golden Gate Fields comes to a close as California racing struggles to exist

- Share via

Of all the great racehorses who have run in California, few had the magic attached to their reputation like Silky Sullivan. He was known for his come-from-the-clouds racing style, making up unfathomable amounts of distance in the last part of the race and usually making it to the finish line first.

Even though he gained most of his acclaim by winning the Santa Anita Derby in 1958, making up 28 lengths, it was at Golden Gate Fields as a 2-year-old that he won the Golden Gate Futurity by coming from 27 lengths behind.

After he retired, he was bought by the Golden Gate owner Kjell Qvale and starting in 1965 he was paraded out on St. Patrick’s Day at Golden Gate and Santa Anita Derby day in Arcadia. It’s even said, but not verified, that Silky Sullivan had his own secretary to answer fan mail.

So, what’s all that got to do with Sunday’s final day at Golden Gate Fields after 83 years of racing?

He’s buried in the infield between the tote board and far turn of the grass course.

“It’s one of my main projects after this week,” said David Duggan, chief operating officer at Golden Gate Fields. “This summer we will be moving Silky Sullivan to Georgetown, Kentucky, to Old Friends [horse retirement park]. We’ll get him re-interred. He has a lot of fans around the country that have been inquiring and that’s the plan.

The closure of Golden Gate Fields is just one problem California horse racing faces. Non-competitive purses and a sinking foal crop paint a tough picture.

“There is some speculation that Lost in the Fog is out there [in the infield] but I can absolutely, categorically assure you he is not. We know exactly where he is and he will be going to Old Friends also. He’s with his previous trainer.”

A grave and Lost in the Fog somehow fittingly describes the current state of Northern California racing. Except unlike the remains of Silky Sullivan and Lost in the Fog, racing doesn’t know where it will end up.

Sunday’s final day has eight races with 54 horses. It’s a far cry from 1949 when a 19-year-old Bill Shoemaker started riding at Golden Gate. Or the following year when Noor defeated Triple Crown winner Citation in a series of races, including those at Golden Gate and Santa Anita.

Longtime horse players will shed a tear and the memories will come flooding back about what makes Golden Gate so special.

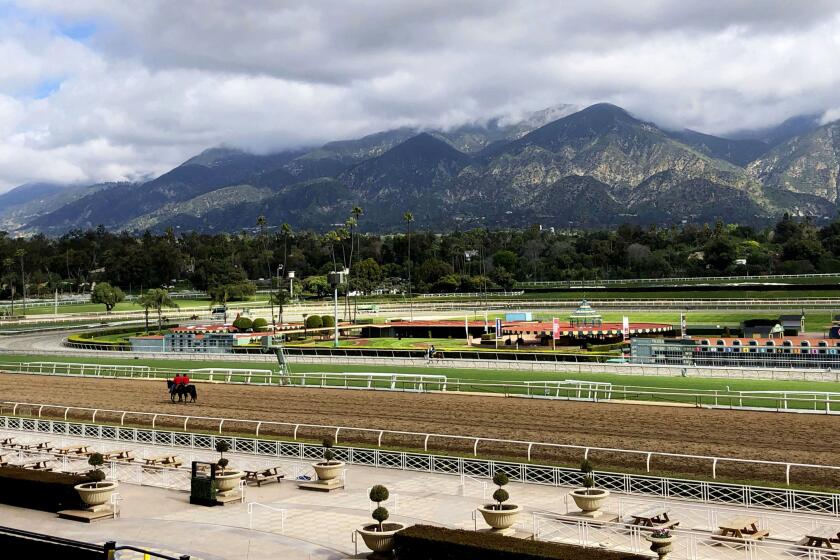

“Golden Gate Fields is a beautiful small track built into Fleming Point, it’s a natural amphitheater,” said Alan Balch, currently the executive director of the California Thoroughbred Trainers who formerly headed a company that did advertising, marketing and public relations for Golden Gate and Bay Meadows from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s.

“It’s a tremendous place to watch the races. It’s very accessible to all of Northern California because it’s right on the freeway and faces the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s just a great place.”

Racing in Northern California started in the 1930s with the fair circuit, a series of small meets held in conjunction with county fairs. It was as much a byproduct of trying to stimulate the economy after the Great Depression as anything else. Building grandstands for racing and supporting the local agriculture community was the real impetus.

Ground was broken in late 1939 on 130 acres of prime property that sat both in Albany and Berkeley. On Feb. 1, 1941, the track opened but it lasted only five race dates before the racing surface washed away, the track went bankrupt and it transitioned to a far more noble role.

As the United States entered World War II, the facility was an equipment depot for the military. It reopened as a race track in 1947 and has been running every year since … until next week.

“It was a huge contributor to many people, thousands of people started thousands of careers here,” Duggan said on Tuesday. “It was a part of the war effort shortly after it opened and the old girl did a great service to anyone in America who was involved in horse racing. So, the accolades it will get are very well deserved and they will be played out over the next few days, weeks, months and even years.”

Jamey Ough, a former intra-track announcer and now a handicapper, feels for the area after Golden Gate closes.

“It has meant that there has been a place for people in Northern California to get to know horse racing and enjoy it,” Ough said. “At Golden Gate we’ve sometimes done some good things to bring that along. Sometimes we haven’t paid as much attention as we should have. It’s its own ecosystem like many race tracks.

“It used to be a bigger economic boon to the area but it still is. When Golden Gate goes away, the trainers will go away and the grooms will go away. They will stop buying things. They will stop going to their favorite restaurants, their favorite bars. “

Frank Mirahmadi, who called the Belmont Stakes on Saturday for Fox and also serves as the regular race caller at Santa Anita and Saratoga, worked parts of the Northern California circuit for almost a decade.

“Any time a historical venue leaves it takes a part of you away, no matter what,” Mirahmadi said. “It won’t be the same without Golden Gate Fields. Hopefully the plans [for a replacement circuit] will be successful. It’s a legendary location. It’s sobering and there’s also an element of sadness to this happening. It’s a beautiful facility that had some incredible moments. … There is nothing that can replace Golden Gate Fields, it’s just going to be different. We need the industry to figure this out and stay strong.”

So, if everyone loves Golden Gate Fields, why does it have to go away?

Golden Gate Fields, as has much of horse racing, has been in decline for a while. Competition from other gaming and a lack of public appetite for racing has provided obstacles. No problem is bigger in California than it has no supplemental income from gaming sources, such as Kentucky. It leaves fewer horses running for smaller purses and fewer gamblers because many don’t like to bet races with just a handful of horses.

No one would have been surprised that Golden Gate was closing until, of course, when it happened.

The Stronach Group, which owns Golden Gate and Santa Anita, bungled the closure by keeping it secret even from the owners and trainers who built the sport. It wasn’t until The Times called TSG executives on July 16 of last year, a day before it was scheduled to be announced, that they hurriedly told longtime employees and tried to break the news to stakeholders ahead of the story.

The feeling for TSG, the racing arm now rebranded 1/ST Racing, is intensely negative among racegoers. There was even discussion of a trainer boycott on the last day, but it didn’t develop.

Nobody could make a strong business case for keeping the track open. It needed a new synthetic racing surface and many improvements to the infrastructure, all with declining revenue. Stronach executives, at times, told stakeholders the track was making money, while the opposite was true. They told the California Horse Racing Board that losses over the last 10 years have been $30 million.

Q&A with Aidan Butler, the CEO of 1/ST Racing, who answers questions concerning the future of Santa Anita Park. How long can it survive losing money?

The track was originally supposed to close at the end of last year. But TSG made a deal with stakeholders that if they didn’t oppose legislation that would funnel Northern California simulcast money to Southern California, meaning Santa Anita and Del Mar, that it would keep it open until June of this year.

Golden Gate made more money by not running every race card this meet. It canceled several Friday cards because of a lack of horses. It even had an underpayment, a surplus of money designated for purses, of about $250,000. That money will be paid back to owners whose horses finished first through fifth in races run this meeting at Golden Gate.

The purses declined so much that the Pleasanton fair meet and Turf Paradise in Arizona, paid bigger purses.

Santa Anita faces the same challenges for survival as Golden Gate but it hopes the diverted simulcast revenue money can help stave off what could be the end of the self-titled Great Race Place.

The recurring theme about what people will most miss about Golden Gate is the sense of community.

“It was a blue-collar track,” said Robert Hartman, who was general manager at Golden Gate from 2005 to 2011 and currently heads the renowned Race Track Industry Program at the University of Arizona. “It was welcoming to everyone, every ethnicity, every demographic, every socio-economic status. It was really kind of the track for everyone and felt welcome there no matter your background. It was great to see that because sometimes in life we don’t get to see that mixture, as people tend to stay in their own groups, but it was a melting pot for the Bay Area.”

Ough remembers how he was assimilated into Golden Gate.

“The cool part is if you went there long enough, you could be part of the family,” Ough said. “You could be an extended part of the family as just a weekend warrior. Back in the day there was a community of family that came in through the free gate, waiting for the gate to open five or 10 minutes before the eighth race. Then there was the feature race and then the last race where you had a chance to go from the $5 exacta to the $2 exacta, which was more my speed back then.

“All those people who lined up at the gate started to know each other. All of it meshed and there were all of these little community or family groups. It just depended on where you wanted to be. If you were a weekend warrior you could end up meeting a trainer, who would ask you to come by. I’ve known plenty of bettors who ended up as hotwalkers for a while just to try it out.”

That feeling of community is also what Balch remembers.

“One of the advertising lines, probably from Sam Spear, is ‘Where the Bay Comes to Play’ because it was in the East Bay and was a great melting pot,” Balch said. “Horse players of all ethnicities would make Golden Gate a great place to be. All the different languages, it was just that kind of place where everybody was there loving the races. That’s what I love about Golden Gate because it was such a magnet. The content of the crowd was just fantastic.”

The CHRB voted unanimously to give Pleasanton racing dates at the end of the year despite a letter from Santa Anita threatening to close or sell.

Horse racing loves its longshots and that might be the story of Northern California racing.

A group called Golden State Racing is likely to get a license to operate 26 race dates from Oct. 19 to Dec. 15 in Pleasanton, where the fair also operates a meeting. The problem is there is no turf course at Pleasanton and about half of all racing at Santa Anita and Del Mar is on the turf.

A proposed agreement, or set of benchmarks, between Golden State Racing and the Thoroughbred Owners of California calls for a minimum of three days a week, 24 races a week and purses of no less than $4.42 million. This weekend (Friday through Sunday) at Santa Anita, the track has only 12 dirt races with the rest on the turf. It would take something very unforeseen for Golden State Racing to meet its benchmark of 24 dirt races a week.

There were about 1,000 horses at Golden Gate and 2,000 at Santa Anita.

Larry Swartzlander, who is one of those heading up the Golden State Racing effort, was asked in December about the chances for success.

“I’m a positive guy, so I say 60% is good number,” he said.

Golden Gate has always known its place, at least recently, in the California racing ecosystem.

“I think the people in Northern California understood the level of racing we had,” said Calvin Rainey, who has been at the track for 40 years, serving as general manager for many of those and is now a safety steward. “A lot of riders grew up here. Victor Espinoza is an example of one who did their early years here. Juan Hernandez is a good example. A lot of these riders as they got better had the opportunity to move to Santa Anita. This was a training ground for many of them to get started.”

Balch sees the track as vital to California’s flagging breeding industry.

“Mother nature only makes so many great horses, just like mother nature only makes so many top baseball players, golfers or anything else,” Balch said. “Just as Major League Baseball has its minor leagues, horse racing has its major leagues and minor leagues and it’s critically important that wherever the top horses are racing that there is a place for the other horses to go.

“California Chrome became the best horse in the world and he was a California-bred. I don’t want to say California-breds are inferior but they can’t always compete at the highest levels and they have to have a place to run. Trainers and owners have to find a place where their horses can win and build confidence.”

The absence of Golden Gate Fields is tough on everyone, with the track likely headed for a date with bulldozers.

“It’s like those stages of grief,” Hartman said. “First it’s denial and then you are angry about it and then you get to that acceptance phase and I’m there. But I’ve gone through those stages. I never thought there would be a closing day but thought there would be some white knight at the last minute, but here we are. It hasn’t happened and I hope it’s not going to happen.”

If it does, and it likely will, the last race is scheduled for 5:20 p.m. PDT on Sunday. A one-mile allowance on the turf. There are eight horses entered.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.