1988 USC vs. UCLA: Rodney Peete conquers the measles then topples the Bruins

- Share via

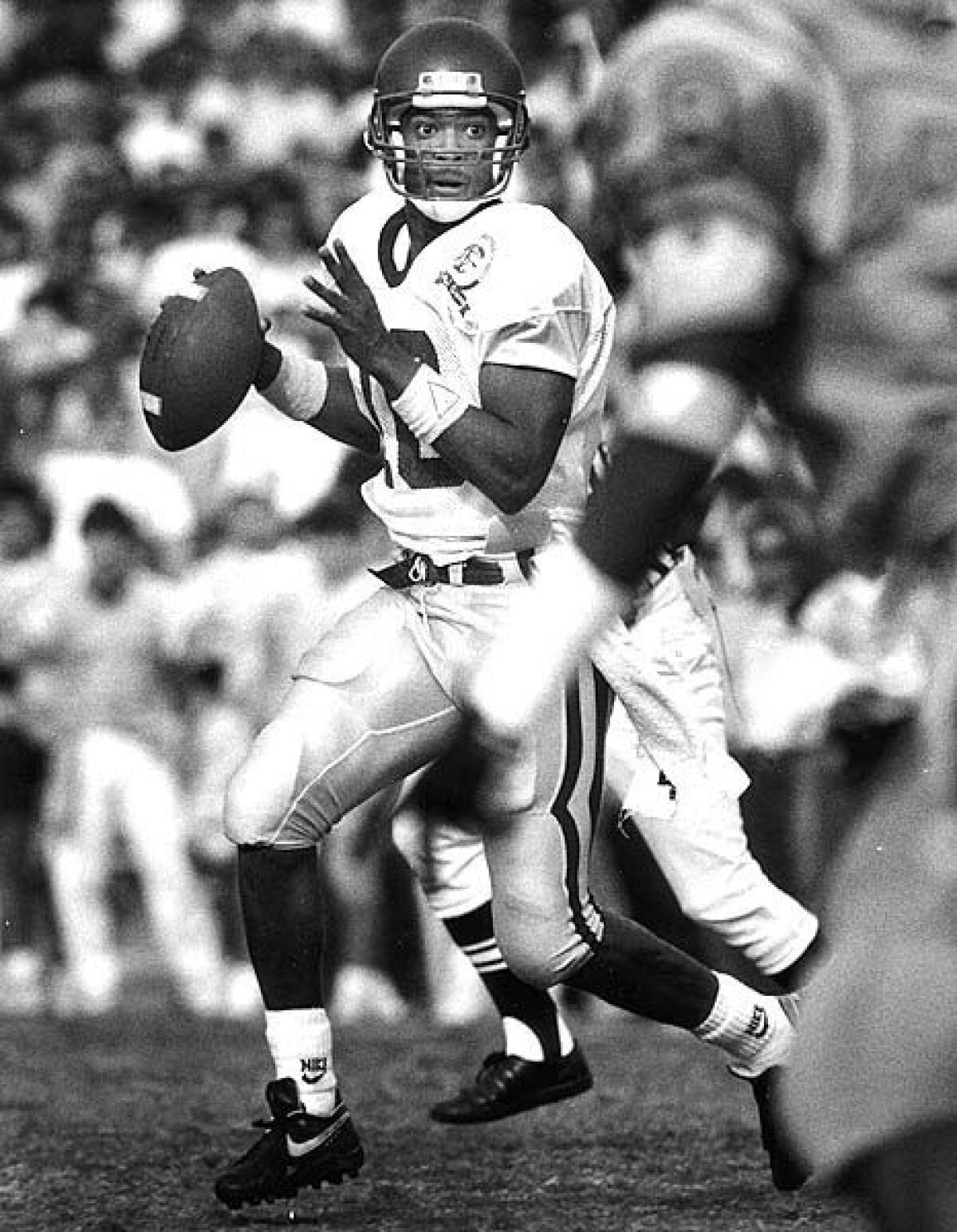

This wasn’t Rodney Peete’s first bus ride weaving through Pasadena on the way to the Rose Bowl, surrounded by a spectacular sea of blue and gold and cardinal and gold flowing in every direction. But this second crosstown trip to play UCLA certainly felt different for the USC quarterback.

For one, 1988 was his senior year, and the 9-0 Trojans and 9-1 Bruins were competing not only for the Pac-10 championship but also to stay alive for the national championship. And then, there was the fact that Peete had just gone through the wildest week of his decorated college football career, a sequence of sickness, subterfuge and secrecy that led to a sight he would never forget as the USC caravan pulled closer to the stadium.

“I see all these students, dressed in UCLA gear, and I would say about 80% of them have polka dots on their face,” Peete recalled recently. “A lot of them had doctors’ masks on. Amazing.”

What was more amazing? That Peete had actually gotten the measles, a contagious respiratory infection mostly contracted in children, as a young adult? Or that today, 30 years later, he still hears from UCLA fans who doubt whether he actually had them, believing that the whole episode was an elaborate hoax meant to distract their team during game-week preparations?

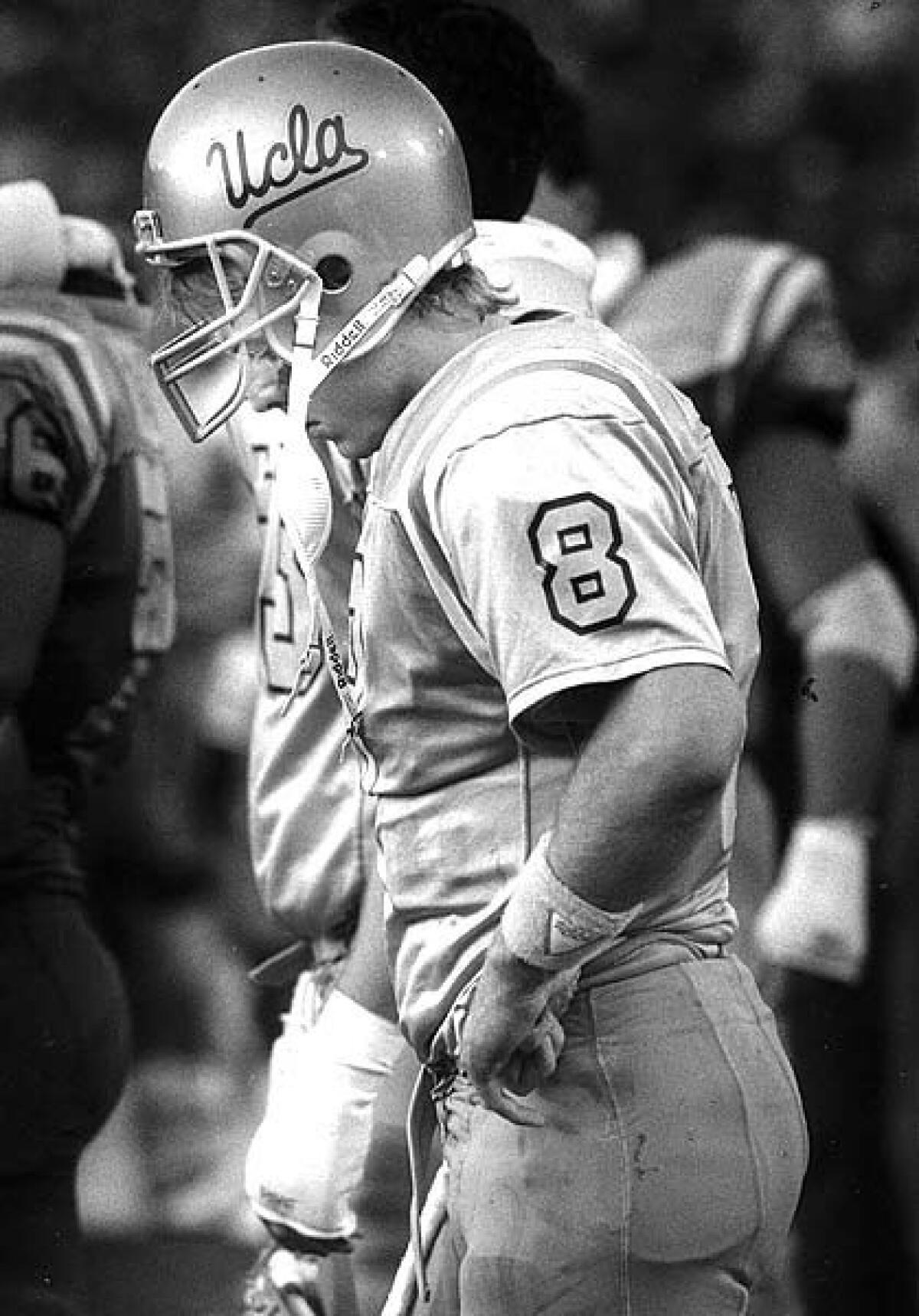

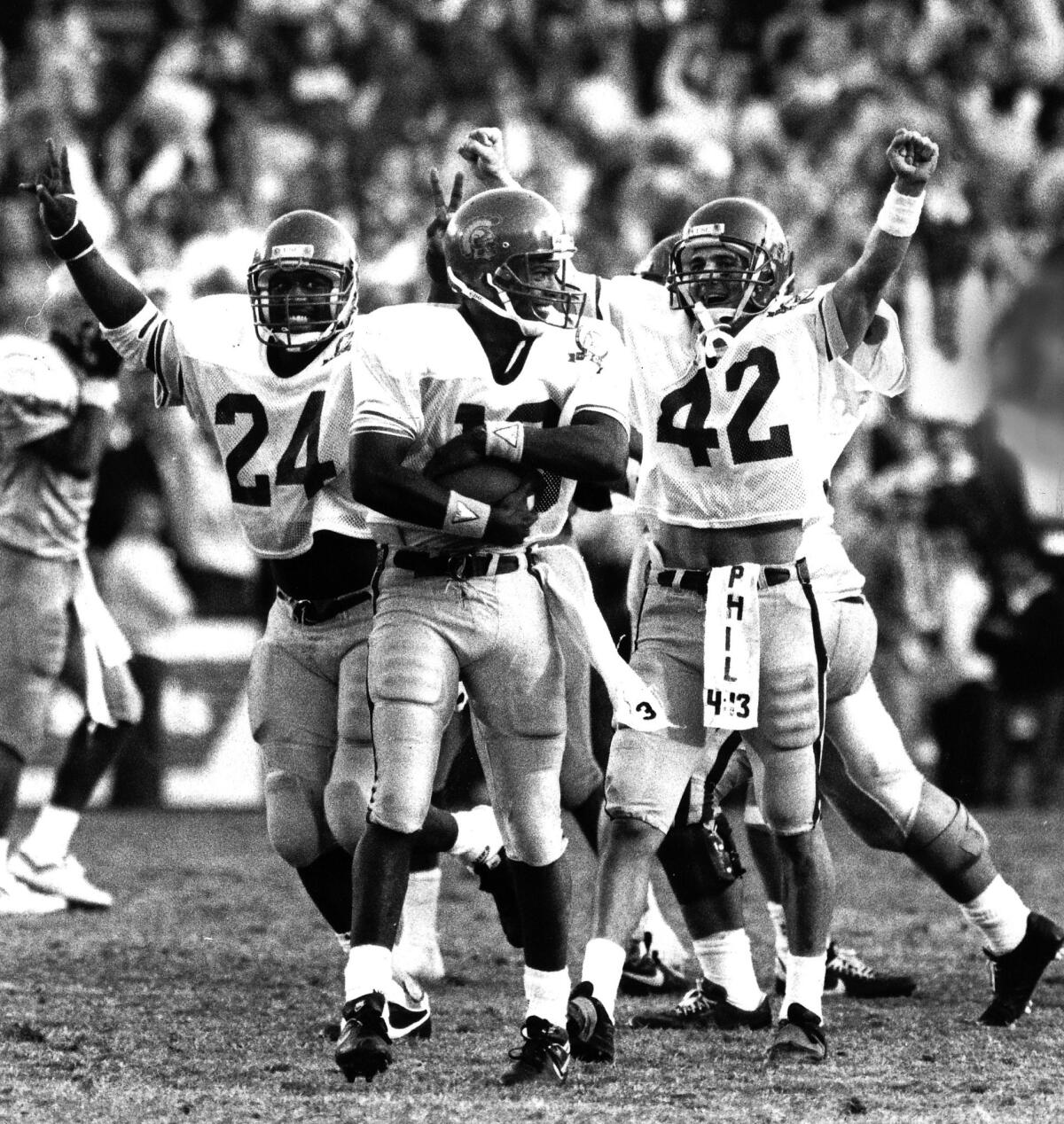

For heartbroken Bruins fans, it has been easier the last three decades to focus their angst on the mystery of Peete’s measles than the actual result of the game, a 31-22 USC victory that sent the Trojans back to the Rose Bowl game and ruined Troy Aikman’s last chance to take UCLA there.

“I had my hopes set on the Rose Bowl,” Aikman said in the moments after the loss. “That’s the reason I came here … and I didn’t do it. That really hurts.”

Aikman went on to win three Super Bowls with the Dallas Cowboys and have his bust enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. But the disappointment of his final college game in the Rose Bowl apparently remains, as he recently turned down a chance to discuss the “Measles Game” with the Los Angeles Times.

And hey, if Peete’s measles had actually limited him in the game, leading to a Trojans defeat, he probably wouldn’t have been so willing to reminisce. Peete played 16 years in the NFL, many of them as a backup, and so the memories of that week live in a time capsule he’s all too happy to open.

“It’s hard to believe it’s 30 years ago, but time flies,” said Peete, who lives in Beverly Hills and co-hosts “Lunchtime with Roggin and Rodney” weekdays on AM 570 LA Sports. “People come up to me and say, ‘I was at the Measles Game,’ ‘I remember the Measles Game,’ ‘Did you really have them?’

“I always answer, ‘Back then, we didn’t need gimmicks to beat UCLA.’ ”

Even today, Peete sounds like a kid who grew up wanting to be a part of the USC-UCLA rivalry and got to live that dream. When he was a boy, Peete’s father, Willie, was an assistant coach at Arizona, and, to young Rodney, it seemed every year the Pac-10 champ was decided when the Trojans and Bruins played at season’s end. Peete chose to play at USC, and he took a 2-1 record against UCLA into his final crosstown rivalry game.

The Saturday before, Peete and the Trojans had pounded Arizona State 50-0 in Tempe, and Peete didn’t feel anything but jubilant. But on the plane ride home, he began to feel nauseous.

Looking back, it’s hard to know how he would have gotten the measles. But longtime USC sports information director Tim Tessalone remembers seeing Peete “kissing babies” after the Arizona State win. At the time, it just seemed like something a Heisman Trophy candidate should do. Maybe someone would capture it in a photo, and maybe it would end up in Sports Illustrated or something.

Two days later, on Monday of UCLA week, Peete called Tessalone with some bad news. He had started to feel as sick as he’d ever felt in his life. He could hardly sleep Sunday night. He called team doctors on Monday, and, after examining him, they swiftly took him to a hospital in Pasadena.

This is where the story gets a little whacky. USC was trying to keep Peete’s condition quiet, but Peete had been spotted by a sports radio personality who happened to be getting dialysis at the hospital in Pasadena, Tessalone recalled. So on Tuesday, USC quickly transported Peete to a new hospital, St. Mary in Long Beach. There, they checked him in under a false name.

“Willie Jackson,” Peete said with a laugh, “which is my dad’s first name and my mom’s maiden name. If you’re any kind of detective, it wouldn’t be hard to find out.”

By Wednesday night, Peete began to feel like he could play Saturday. But he and the coaches weren’t going to let that out, particularly with the news of his hospitalization getting out and UCLA now preparing as if Peete might not play.

Thursday night, Peete tuned in for the local nightly news.

“I’m sitting there in the hospital,” Peete said, “and the opening story of the 11 o’clock news was Rodney Peete is still in the hospital and doesn’t know if he’s going to play in the USC-UCLA game.”

When Peete returned to USC practice Friday, reporters from around the nation had converged on campus, hoping for any update on his status. The Trojans sneaked him in and out of a back entrance by the baseball stadium.

Somehow, as that bus rolled up to the Rose Bowl a day later, it was still unknown to most whether he would play in the game.

This aspect is what makes it a quintessential 1988 story.

“Nowadays,” Peete said, “I would have been out there posting on Instagram or on Twitter, ‘Hey, I’m in the hospital, I’m going to play, I’ll be all right,’ as opposed to keeping everything a secret. It would have been out, easily. There’s no way to hide anything nowadays.”

Peete walked onto the Rose Bowl field for pregame warmups and heard many cheers from fans who saw the kid in the white No. 16 come out of the tunnel. That was thrilling, but the nerves started to creep in about how he would perform. Peete had lost 12 pounds in just a few days. He worried about his stamina.

The adrenaline carried him. He completed 16 of 28 passes for 189 yards and a touchdown and ran for another score. Aikman had the bigger stats — 317 yards and two touchdowns — but Peete got the win and a story to tell for the rest of his days.

“We joke about it,” Peete said of Aikman. “In his mind, if it was him, he would have had to be on his death bed not to play. He always knew I was going to play no matter what.”

The next week, No. 2 USC welcomed No. 1 Notre Dame to the Coliseum. It was the only time the storied rivals have played when ranked atop the polls. The Fighting Irish beat the Trojans 27-10 and went on to win the national championship. USC lost to Michigan in the Rose Bowl 22-14.

Peete wonders if the Trojans expended too much emotional energy getting through the Measles Game.

“People will say that’s an excuse, but it’s a real thing,” Peete said. “You just won the Pac-10 and you’re going to the Rose Bowl, that’s a celebration in itself. And naturally there’s going to be some sort of exhale and relief, but you do have to get up the next week, which is another big game. It’s not an excuse but a reality of human nature.”

The loss to Notre Dame soured the 1988 season for Peete for a couple of years afterward.

But today, he can think back on those final seconds of the Measles Game with renewed perspective at what he and his team had accomplished.

“We were running out the clock at the end,” Peete said, “and my whole career at ’SC just started flashing through me, the week and everything. It was an amazing feeling playing in that game.”

Twitter: @BradyMcCollough

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.