It’s not a Rose Bowl without Jim Hardy at the Pasadena classic

- Share via

Jim Hardy, who is 93 years old and will soon attend his 85th Rose Bowl game — so long as he can get over this damn cold — has just finished pantomiming a quarterback’s scramble, around his living room, when he lets out a single cough.

He’s awfully sick, he claims.

“That Notre Dame game,” he says.

“We sat out in the stands in just our shirts in the sprinkles,” says his wife, Henrietta, who is 92 and sitting across from Hardy on a couch in their house outside Palm Springs. “It was freezing!”

“Well, I wasn’t about to leave that game,” Hardy says early in December. “If there’s anybody’s ass I like to see get kicked, it’s Notre Dame’s, you know? Especially if the Trojans are doing the kicking.”

Hardy has a few weeks to recover, and anyway, no one expects him to consider missing the game. From the time USC played Tulane in the 1932 Rose Bowl to the present — a period that for Hardy has spanned one professional football career (including seasons with the Rams), one world war and decades of one marriage — Hardy hasn’t missed a single year’s game in Pasadena. Eighty-four times, he has celebrated the new year with football. Eighty-four times, he has seen the sun plunge behind the San Gabriel Mountains. The folks at the Rose Bowl don’t keep an official tally, but Hardy’s is believed to be the longest attendance record in the nation’s oldest bowl game.

“The only type of attendance streak anywhere close to that (that we are aware of) would be Art Spander’s,” said Doug Ingels, a media coordinator for the game, in an email. Spander, a longtime sportswriter who will be inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame this year, has attended 63 straight, which puts him in exclusive company. Hardy knows of one other person whose record exceeds Spander’s, though not over consecutive years.

Asking Hardy why he returns each season is like asking a football why it returns to the earth after a kickoff. It is almost a rule of nature.

Hardy’s folks were pulled west as if riding similar gravity. His father, an Okie whose parents were on the starting line during the land grab, worked the telegraphs for Western Union. Hardy’s mother was born to a father who quit work at a lumber mill in northern Michigan in favor of the mines of Idaho, where a dynamite charge blew out his eyes. Each morning afterward, Hardy’s mother guided him downtown to sell chewing gum, tobacco and candy bars. Eventually, the blind ex-miner opened a dance hall, which is where Hardy’s father, the new telegraph operator in town, met Hardy’s mother. The pair settled in San Pedro.

The job took Hardy’s father to Los Angeles’ press boxes, where he’d tap out the sportswriters’ dispatches. Hardy estimates his father was working the 1923 Rose Bowl, the first appearance for USC and Penn State, and the first in the new stadium.

When Hardy was old enough, his father brought him along. His first USC game was 1931, when the Trojans whipped Georgia, 60-0. He went to his first Rose Bowl a few weeks later.

Each night from then on, Hardy, an Irish Catholic, would kneel before bed, close his eyes and pray, “Please make me a USC football player,” a request that was answered. He played in two Rose Bowls and was the most valuable player in one.

Around him, Los Angeles boomed, the world changed, Hardy built a life, and the Rose Bowl stayed the same — same mountains, same blue sky, same parade, same game.

I can still punt and make it turn over. And I can still throw a tight spiral.

— Jim Hardy, age 93

His first Rose Bowl was six years before the Army Corps of Engineers laid down concrete in the Los Angeles River. His favorite game was probably 1935, four years before Union Station opened, when Alabama, one of the best teams he’s ever seen, walloped Stanford.

Hardy did miss one year: 1942, when the game was played in North Carolina because of fears of Japanese bombing. Hardy joined the war after graduation, shipping out on the USS Maryland in 1945. Victory came shortly afterward. The ship was in dry dock on New Year’s Day, 1946. Hardy took leave and went to the game.

Hardy, who was the longtime general manager of the Coliseum, still follows the Trojans zealously. About once a week, he drives to Los Angeles to watch practice, 130 miles each way through the desert. (The cold never had much of a chance after all; Hardy was back at practice during bowl preparations.) He attends all the home games. He can be a blunt critic, but he says he would cut off body parts for a chance to play for Coach Clay Helton.

Hardy’s memory is remarkably clear. He can recite the starters on each team he played against, plus the scores of half the Rose Bowl games, and he will, at great length. He now appears to have lost interest in committing new names and figures to memory. USC’s Sam Darnold is simply “This New Quarterback,” and Hardy adores him.

All of a sudden, Hardy is off the couch, scrambling around a coffee table with an imaginary football, doing his impersonation of This New Quarterback.

“He comes back, and he’s back here, and they blitz and guys get through and he steps outside, and now he can run or pass, and he’ll take off and run and make 15 or 20 yards,” Hardy says. “You know, the guy is remarkable. He’s only a freshman!”

Hardy returns to the couch, not quite winded.

“I can still punt and make it turn over,” he says. “And I can still throw a tight spiral.”

Hardy goes to the gym three or four times a week. He doesn’t golf anymore, but he walks a local course in the mornings.

The only one who has been able to keep up is Henrietta, whom everyone calls Hank.

“They are always on the go,” their daughter, Ellen, says. “They are exhausting.”

Hardy, looking across the room at Hank, says that he couldn’t take his eyes off her in philosophy class at USC. He realized that Hank was “the same little tomato” he’d had a crush on when he’d seen her at a high school football game a year earlier. He worked up the nerve to ask her to study together. She agreed. He asked her out. She declined. He was the football star, not used to rejection, but football didn’t interest her. He persevered. Eventually, they went on a date to the Hollywood Palladium (“She’s the greatest swing dancer who ever lived,” Hardy says) and the Santa Monica Pier.

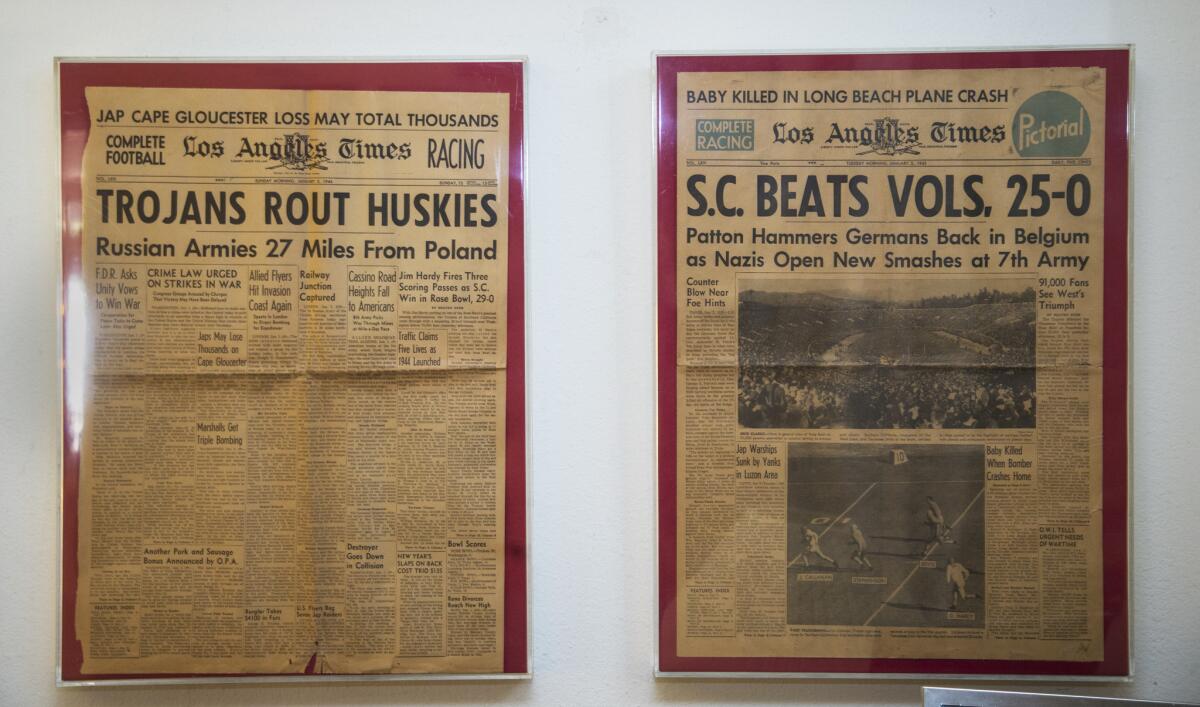

Front pages of newspapers from 1944, left, and 1945 hang on a wall at Jim Hardy’s home in La Quinta.

The football season had maybe four games left, Hardy says, and Hank still refused to so much as read the sports page of the Daily Trojan.

“Nor,” Hardy says, still a little wounded, “did she know that I was playing —”

“Well, I knew that, yes, but see, I didn’t care,” Hank says. “It meant nothing to me.”

“May I finish this story?” Jim says.

They kept dating, Jim continues, and the Trojans kept winning. In the 1945 Rose Bowl, perhaps Hardy’s greatest triumph, he threw for two touchdowns, ran for another, and pinned several punts inside the 10-yard line as USC took down undefeated Tennessee, 25-0. And better yet, Hardy had a date with Hank that night.

“I’m so full of myself, I can hardly wait to unload how important I am,” Hardy says.

He drove to the Valley, knocked on the door and awaited the adulation.

“She didn’t know there was a game,” he says. “Her family never gave a damn about football, so they didn’t have it on radio or TV.”

“Well, we didn’t have TV,” Hank says.

“Yeah? Well, you wouldn’t have been watching it either,” Hardy says.

Hank reformed — or acquiesced. Eventually, she learned to love the Rose Bowl. The only attendance record Hardy knows of longer than Spander’s? It’s Hank’s. Feeling guilty, she didn’t miss a game after Hardy’s MVP performance in 1945, save a few missed years when she was pregnant.

“It seems so American,” Hank says.

“And the bomber flies over before kickoff …, “ Hardy says.

“But the whole thing,” Hank says. “The panoply, the grandeur, the wonder of it! The beauty of that place being in the Rose Bowl and having 100,000 people surround you, and the sky, and the mountains around. It’s just so wonderful.”

Hardy, on the couch, is looking proud.

Follow Zach Helfand on Twitter @zhelfand

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.