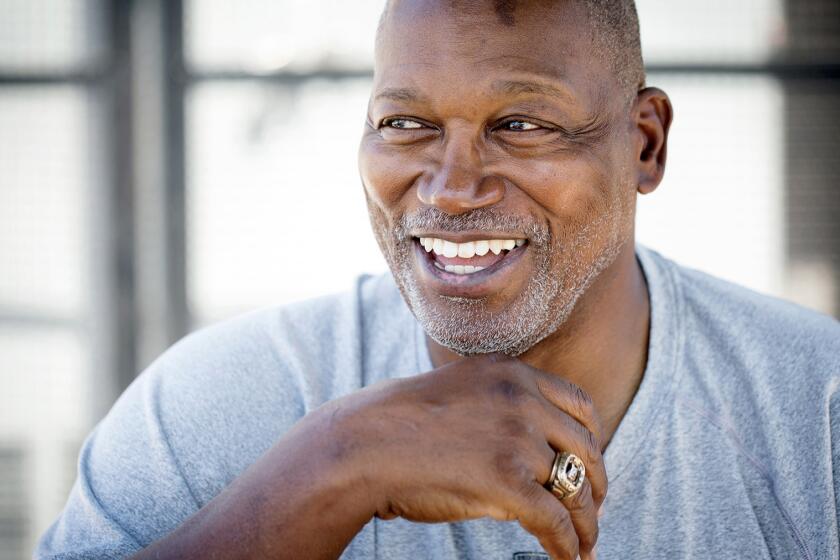

Sam Cunningham, USC player who helped integrate college football, dies at 71

- Share via

College football still clung stubbornly to segregation in the early 1970s. There were still teams at major universities, in some parts of the country, that refused to put Black players on the field.

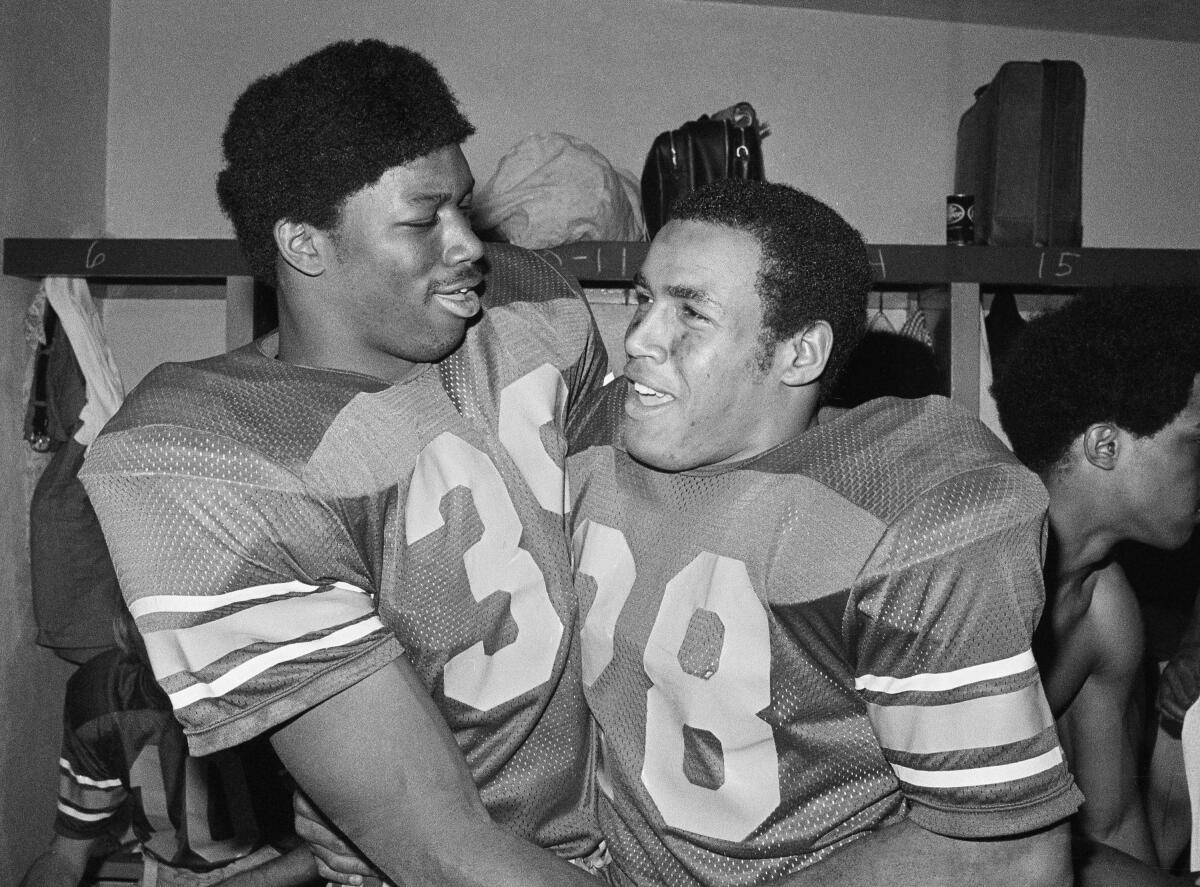

The powerhouse Alabama Crimson Tide were chief among the holdouts, which made their game against USC in the fall of 1970 such a big deal. Not only did the Trojans bring an integrated roster to Birmingham, but they also had a Black fullback named Sam “Bam” Cunningham.

Built thick and strong, earning his nickname by crashing into the line of scrimmage time and again, he led the Trojans to victory with 135 rushing yards and two touchdowns, showing the segregationists what they were missing. Though that Saturday afternoon often has been embellished upon retelling, there is little doubt it played a crucial role in integrating the sport.

“I’m just proud to be a part of it,” Cunningham told the Times in 2016, “because it was such a special game.”

The Santa Barbara native died Tuesday in Inglewood at 71, USC officials announced. No cause of death of death was given.

Several years after Sam “Bam” Cunningham helped an integrated USC football team whup an all-white Alabama team in 1970, Cunningham traveled to Montgomery, Ala., for a golf tournament.

Born Aug. 15, 1950, Cunningham became a star athlete at Santa Barbara High, one of four brothers who played for the Dons. His younger brother Randall Cunningham later became a marquee quarterback in the NFL.

Freshmen weren’t eligible for the varsity team when Sam Cunningham arrived at USC in 1969, but at 6 feet 3, 212 pounds he immediately broke into the starting lineup as a sophomore. That didn’t sit well with teammate John Papadakis, who got switched from fullback to linebacker and vented his frustration in training camp scrimmages.

“The only way I was going to play fullback again was to take his head off,” Papadakis recalled. “I tried but Sam was a guy who wouldn’t back down. We had a fighting respect for each other.”

Cunningham’s college career began with that game in Alabama. The film “Easy Rider,” about a pair of bikers gunned down on a road trip through the South, had just come out the year before.

“Don’t you think that going to Birmingham raised questions in the hearts and minds of us USC players?” said Papadakis, who later collaborated with Cunningham and writer Don Yaeger on a book titled “Turning of the Tide.”

Some players packed knives for the trip. One brought a gun. But, having grown up in Southern California, Cunningham wasn’t thinking about the game that way.

In football terms, the No. 3 Trojans simply were better than No. 16 Alabama, bulling to an early lead at Legion Field and never looking back. John McKay, the late USC coach, pulled Cunningham and the other starters in the third quarter with his team on the way to a 42-21 victory.

The Crimson Tide’s legendary coach, Paul “Bear” Bryant, congratulated Cunningham afterward and Papadakis heard fans talking.

“They told Bear Bryant, ‘We need some of those Sam Cunninghams on our team,’ ” the former linebacker said. “I was there.”

The game spawned a number of urban myths as the years passed.

There is speculation, but no evidence that Bryant put USC on his schedule in hopes of losing and quieting the segregationists who resisted recruiting Black athletes during the George Wallace era. He certainly did not march Cunningham into his locker room after the game and announce: “This is what a football player looks like.”

It was a fallacy that the defeat caused Alabama to sign its first Black player; the Crimson Tide already were recruiting Black players for basketball and had an ineligible Black freshman on the football roster.

But USC’s victory, and Cunningham’s impressive statistics on just 12 carries, may have worked in subtler ways.

USC freshman safety Calen Bullock had a dynamic debut Saturday during the Trojans’ 30-7 win over San Jose State.

Though Alabama had lost to an integrated Tennessee squad the previous season, the Trojans had an all-Black offensive backfield that also featured quarterback Jimmy Jones and running back Clarence Davis. As Jones told the Times in 2000: “It was no ordinary day.”

Alabama fans reportedly were dismayed at losing so badly and, perhaps, enlightened by the performance they saw from a visiting team with more than a dozen Black players on the roster. There was little pushback when the Crimson Tide later sought to fully integrate their team.

Former Alabama basketball coach C.M. Newton worked for Bryant, who doubled as the school’s athletic director, and recalled his boss saying: “I want some guys who can play like those players. I don’t care what color they are.”

McKay said Bryant called to ask “about Black players and how to treat them. I said, ‘Treat ‘em like everybody else.’”

Cunningham later insisted the game “didn’t change how those white people thought of Black people. They were accepted because they could help their program win football games.”

In personal terms, his performance marked an auspicious start to a big-time football career. As a senior in 1972, the three-year letterman was named team captain and made All-American. His four touchdowns against Ohio State in the 1973 Rose Bowl — all of them trademark goal-line dives — capped an undefeated season that earned the Trojans a national championship.

If fans knew him as the runner who launched himself fearlessly over the pile, landing with a thud in the end zone, teammates recalled a sociable and humble guy, someone who always told the truth.

The New England Patriots selected Cunningham in the first round of the draft that spring. He played nine seasons in the NFL, making the All-Pro team in 1978 and retiring as the franchise’s all-time leading rusher with 5,453 yards.

“As much as I admired him as a player, my affection for him only grew after spending time with him and learning more about him as a person,” Patriots owner Robert Kraft said in a statement. “He made a tremendous impact, both on and off the field.”

USC coach Clay Helton offered a similar view, calling him “as good a man as he was a player.”

After football, Cunningham returned to Southern California and started a landscaping business. He is survived by wife Cine, daughter Samahndi and a few more athletic standouts in an extended family. A nephew, Randall II, was a two-time NCAA high jump champion at USC and niece Vashti represented the U.S. in that event at the Tokyo Olympics.

Though his career always would be linked to the Alabama game, Cunningham never seemed to understand why that day had to be embellished. As he said: “It’s already a historic story without adding any sauce to it, you know what I mean?”

And what about talk of him and his teammates as heroes?

“We’re just regular people,” he said. “I didn’t do anything more than what I was asked to do. Run the ball. If there’s a hole, run through it. If you can score a touchdown, score a touchdown. Bam. Pretty simple.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.