Artisans re-create a classical Chinese oasis in San Marino

- Share via

WHILE giving thanks today for all that’s near and dear, it might not hurt to offer gratitude for folks you may never meet: workmen from China who have toiled for six months in San Marino, applying skills passed down through generations and not taught at any schools.

Their creation -- the Garden of Flowing Fragrance -- is springing up like some fantasy film set at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. But it is authentic in all respects. Its design re-creates botanical havens built by scholars who were the social elite during the Ming Dynasty, when the art of classical gardens reached its zenith in the city of Suzhou. When the new garden opens in February, visitors will find handmade bricks, tiles and wood structures, all with elaborate decorative details, all crafted by artisans brought here by the Huntington because their skills are as ancient and rare as the garden design itself. Like its predecessors, the garden sits within undulating white walls, its 1 1/2 -acre lake dotted with hand-carved stone bridges, swooping-roofed pavilions and pebbled paths.

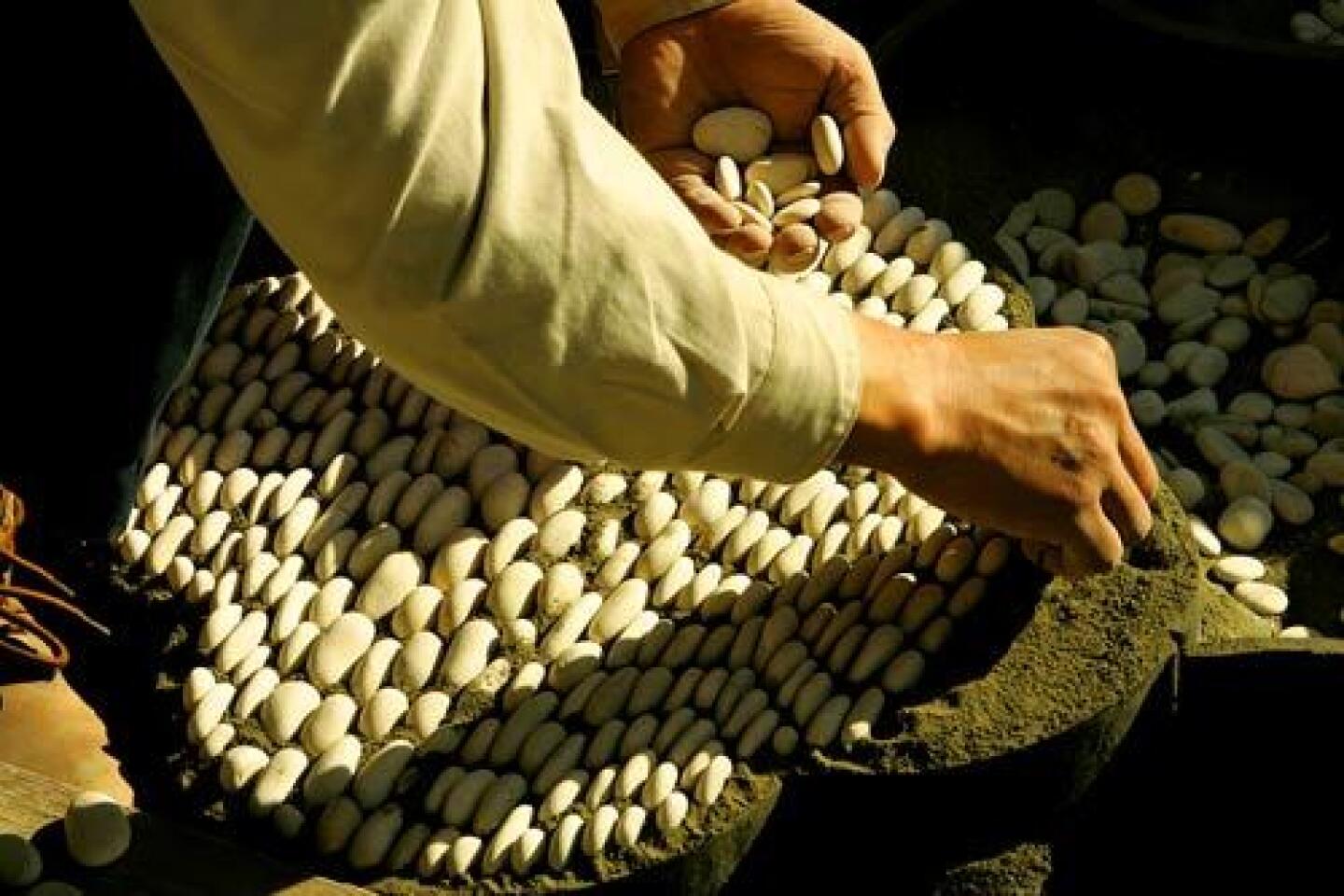

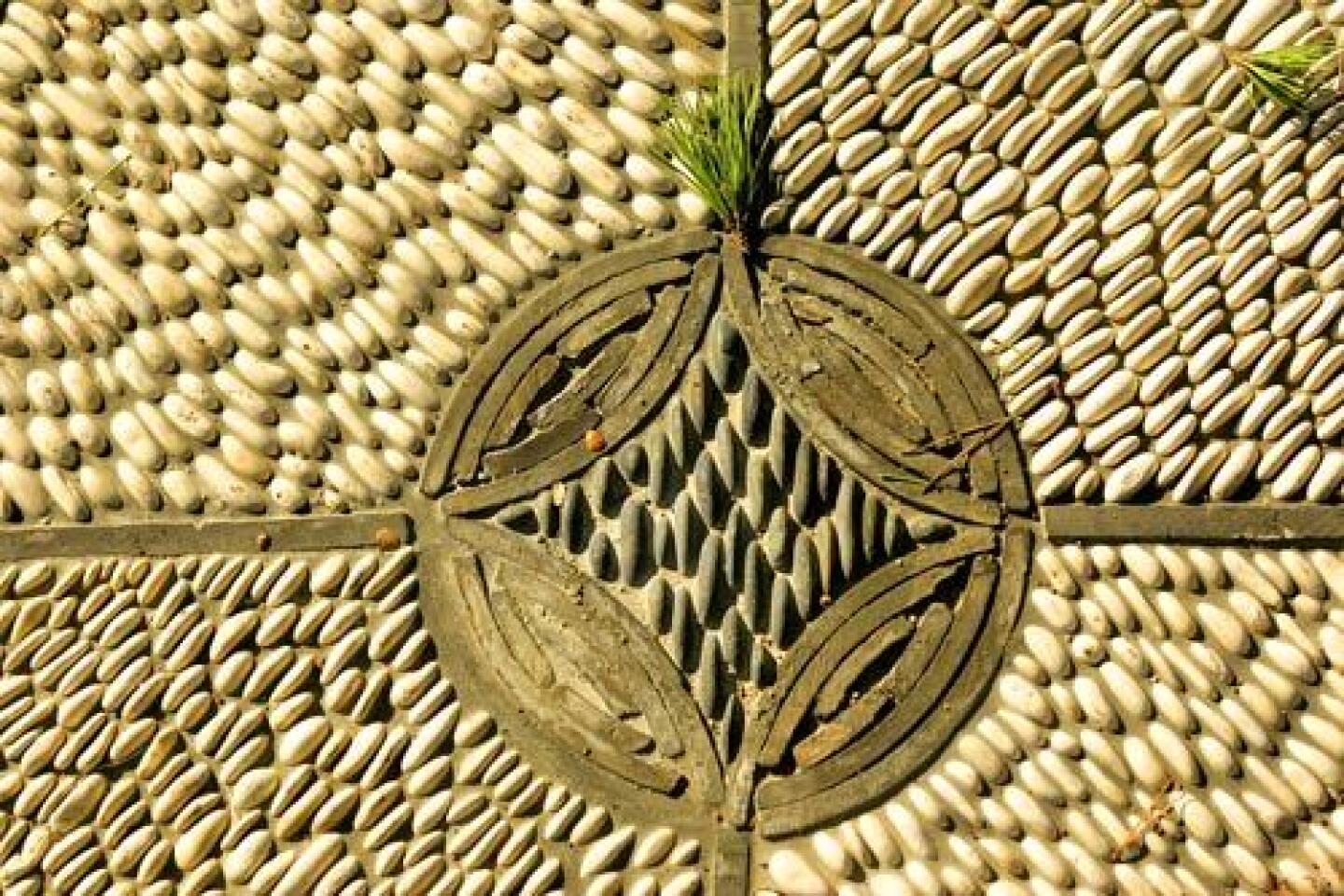

To execute this art, pavers sift through little pails of stones, placing them one by one to form floral patterns that make up the meandering walkways and plazas. They work deftly, finding the right size and shape, gently hammering each into place with a mallet.

Stonemasons who specialize in calligraphy etch ancient characters into the spongy, hole-riddled limestone rock, 850 tons of which were imported from the Suzhou area. Not calligraphers themselves, these men are experts at transferring the masterful inscriptions of artists from paper onto stone. Each carving will tell visitors the name of the pavilion in which they’re standing or will describe the poetry of the view.

The lake is encircled by massive chunks of rock, positioned there by specialists from Suzhou. These men also placed the 8-to-14-foot rocks that serve as sculptures, the kind of natural specimens valued in China since the Ming era for the grace and beauty of their shapes.

Woodwork specialists install the burnished panels of ginkgo and fir, carved or etched with patterns and classical themes passed down through centuries.

In the double-roofed, hexagonal Three Friends Pavilion, the ginkgo ceiling bears images of the three friends of winter -- pine, bamboo and plum blossom -- all of which remain hearty through the cold months. Wood carved into a traditional lattice-like pattern called “broken ice” is set like a delicate frozen curtain.

Tile specialists put finishing touches on pavilion roofs made exactly as they were 500 years ago. Clay is hand-fitted into molds and then fired with rice straw in brick kilns for at least 40 days. The resulting roof tiles are then placed -- sideways instead of flat, and tightly overlapping -- according to custom that has survived the ages. Every tile has been imprinted by hand with a chrysanthemum.

The workmen speak no English but say through an interpreter that they enjoy the Monterey Park area, where they have been housed in a motel and where buses pick them up in the morning and bring them back at night.

They seem less interested in talking about their craft, however, than in practicing it. Indeed, every element of the garden they are creating radiates reverence for art and nature.

THOSE who know little about the Ming era (1368-1644) or about Chinese gardens in general may wonder at the relevance of a 16th century garden in modern Southern California. But that’s exactly why an institution like the Huntington exists, says Laurie Sowd, project manager of the garden. The goal is to preserve the enduring works of those on whose shoulders our world is built.

China, experts agree, has the oldest continuous tradition of garden design on the planet. China is also the origin of many flowers, plants and trees that grow in Southern California today, Sowd says. Camellias, chrysanthemums, wisteria, azalea, hibiscus, bamboo, pines, juniper, willow, some of our roses, many of our flowering trees -- they all were staples of Chinese gardens long before the Pilgrims reached Plymouth Rock.

But this new garden is as much about architecture as it is about horticulture. Eight pavilions, nine bridges, covered walkways and paths that zig and zag are all artfully named to allude to their site as well as to an ancient poem or essay.

The Pavilion for Washing Away Thoughts, for example, is a secluded thatched-roof structure set deep in a canyon, from which gentle sounds of flowing water and rustling trees can be heard.

The Terrace That Invites the Mountain is placed for a glorious view of the San Gabriels; the Love for the Lotus pavilion overlooks the lotus-filled Pond of Reflected Greenery.

Gardens in the Ming era were looked on as three-dimensional paintings, Sowd says. Each pavilion was positioned with gracefully shaped openings framing a carefully planned view. Precise positioning of flowers, trees, sculptural rocks (which represented mountains) and ponds or lakes (which represented oceans) was critical to achieve the most beautiful work of art possible.

June Li, the garden’s curator and the Huntington’s resident expert on all things Ming, explains that names were significant in the complex and layered garden culture of Suzhou, where gentlemen scholars built walled landscapes to get away from the hurly-burly of the outside world and to integrate their love of the natural universe with an appreciation of art and literature.

Each name was thought to lend deeper meaning to each garden. Often, famous scholars or poets were asked to contribute to the naming process. The Huntington has followed suit. A panel of three experts on Chinese culture met with Li in what she calls “convivial conversations” for more than a year before selecting the names of the garden as a whole and the views from structures within. The advisors -- Wan-go H.C. Weng, a New Hampshire-based collector, scholar and poet; Richard Strassberg, professor of Chinese language and culture at UCLA; and Yang Ye, professor of comparative literature at UC Riverside -- all conferred on the garden’s formal name, which was announced in June: Liu Fang Yuan, or Garden of Flowing Fragrance.

“It’s a name I cherish,” Weng says. “It refers to the beautiful scents that will flow through the garden, and to an excellent prose poem by Cao Zhi (192-232) called ‘Rhapsody on the Luo River Goddess.’ ”

Weng describes it as a haunting tale.

“It explains how beautiful the goddess was, how a prince fell so much in love with her and then realized he could never posses her because she was a goddess and he a mere man. It tells how she arose from a patch of magnificent fragrant plants, and wherever she walked she spread that fragrance.”

STRASSBERG says the naming process is one of many qualities that may expand a Westerner’s concept of what a garden can be.

“There’s so much going on in a Chinese garden,” he says. “There’s the unity of landscaping and architecture, because in China the concept of garden includes the concept of house within the garden. There is no distinction between the two.”

In a traditional Ming garden, he says, structures are made of materials that imitate the landscape.

“You have a little raised platform -- that represents Earth,” he says. “The pavilions are a kind of post and bracket construction, with posts made of tree trunks appreciated for the beauty of the wood. At the top of the posts, you’d have a series of brackets that extend out in tiers, like the twigs and branches of trees.”

Due to seismic regulations, the Huntington used structural steel covered with wood. “The roof is placed on these brackets, and usually represents heaven,” Strassberg says. “So the architecture imitates the idea of Earth, trees and sky. Humans dwell in the space between.”

Ming Dynasty gardens of Suzhou were created as manifestations of taste, Strassberg says, and of their owners’ cultural status as scholars, who basically formed the ruling class.

“They had the ability to appreciate and create poetry, painting, music, theater -- and they used their gardens to do all that and more. In fact, any kind of life could take place there, because the space was so ambiguous, the house so much a part of the garden, and the garden so much a part of the house.”

Strassberg says he’s had a garden epiphany because of his involvement with the Huntington project.

“I live in a Spanish Mission-style house with a garden that’s fitting. But I love bamboo and have a corner of the garden with five kinds of bamboo, where I can sit surrounded by it.”

Strassberg says his bamboo corner wasn’t named. “A garden without a name lacks character and soul,” he says. “Naming it is like painting the pupils into the eye of a dragon; it animates and brings it to life.”

Recently he named his favorite spot Little Bamboo Garden and asked Weng, an expert calligrapher, to write the name in Chinese for him.

“He did it on paper, and I’m carving it on wood and hanging it there, just as should be done,” Strassberg says.

The Western garden typically has nothing to do with literature or art, UC Riverside’s Ye says. “But, as Oscar Wilde once said: Life imitates art more than art imitates life.” In Chinese gardens of the Ming era, he adds, the tradition was to imitate art, to mimic great paintings, to think of poetry and calligraphy. In fact, he says, the Chinese use one tool -- a specific kind of writing brush -- to do all three things.

His favorite name in the new garden belongs to the tea shop: Huo Shui Xuan, or Freshwater Pavilion. He says the name has its origin in a poem on tea by the great Chinese artist and poet Su Dongpo (1037 to 1101). It begins: “Living water should be cooked / with living fire.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.