Wildflowers come and go, but in Anza-Borrego, the desert will always be the star

- Share via

I may have missed the spring’s epic wildflower bloom that sent thousands traipsing through this sprawling park to ogle desert lilies and sand verbena, but Anza-Borrego still had a few wonders up its sleeve.

As I hiked through the park in early April, I found deep purple and hot pink flowers sprouting from stands of hedgehog and beavertail cactuses.

Prickly barrels, some more than 4 feet tall, stood like portly princes crowned in florets of orange and gold. And there were graceful ocotillos, willowy arms tipped with blood-red blossoms.

I was heading toward Hellhole Canyon but getting waylaid at every turn by botanical curiosities. I scurried up rocky hills to inspect rotund fishhook cactuses or blooming yuccas, 3-foot spikes jutting from their midsections.

ALSO | Celebrating our national parks »

It was a bit after 10 a.m. and already 93 degrees, the kind of heat that snuffed out those winter annuals that had dazzled a few weeks earlier.

Sure, I regretted missing the big show, but wildflowers come and go. Here in Anza-Borrego, the desert will always be the star.

California’s largest state park

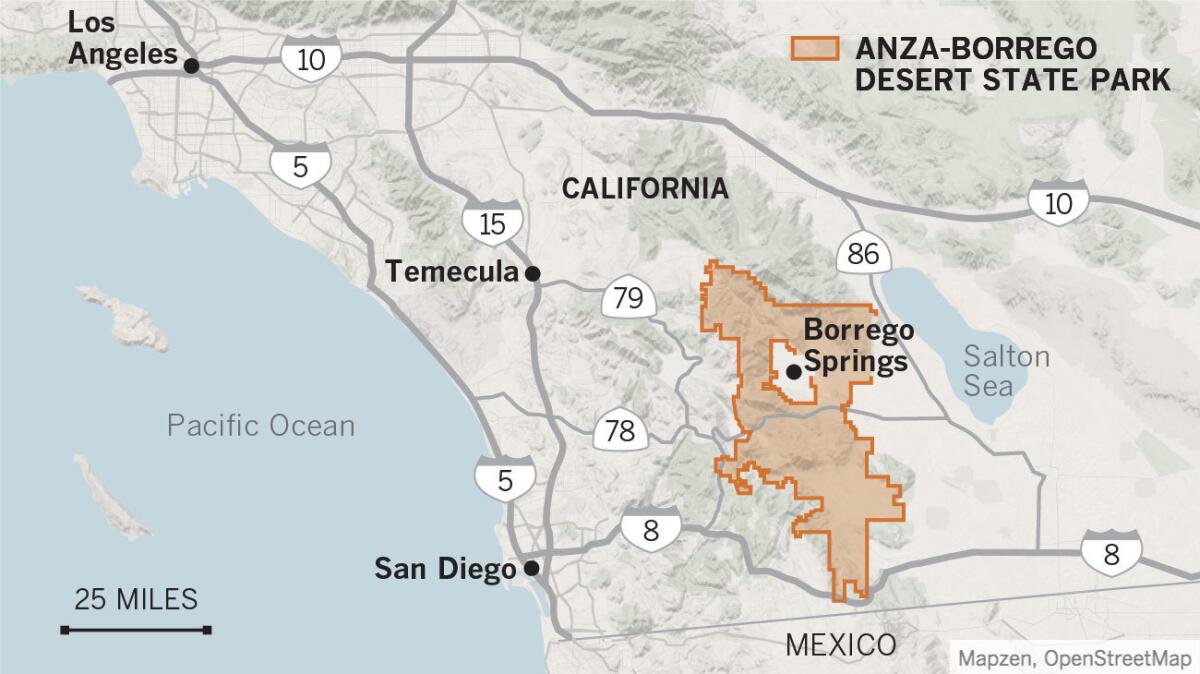

At 640,000 acres, California’s largest state park stretches across Riverside, San Diego and Imperial counties, stopping just a mile or so from Mexico.

Distances can be long, and some spots require four-wheel-drive or high-clearance vehicles. But if you plan properly, even a short visit can be intensely rewarding.

You can see petroglyphs, slot canyons and mud caves. You’ll find plants unique to the Colorado Desert, a subset of the Sonoran Desert. Fossils abound.

You might even foolishly chance your two-wheel-drive vehicle, as I did, down Torote Canyon to observe the rare elephant trees named for their twisted trunks. Think twice.

Or do nothing.

“We have this vast wilderness of desert that is an attraction unto itself,” said Terry Gerson, district services manager for the California Department of Parks and Recreation’s Colorado Desert District.

“You can have solitude where you see no people at all. You can pitch a tent and hang out wherever you want. The ability to see stars and the Milky Way here is unparalleled.”

My family and I were regular Anza-Borrego visitors before moving from California in 2010. We came for the annual wildflower display, of course, but usually we would just park along the road and start walking.

My son tracked collared lizards and the hard-to-find white praying mantis. My daughter scrambled up rocky mountainsides.

I sometimes took long hikes alone, occasionally dozing under rocky overhangs. The solitude was intense, unlike any other park I knew in California.

Once, awaking from a snooze near Alcoholic Pass, I realized six bighorn sheep were eyeballing me from a nearby ledge. Borrego is Spanish for sheep, and about 600 live here.

The most popular hike is the Borrego Palm Canyon Trail, an easy 3¼-mile loop running from the visitor center to an oasis with a seasonal waterfall.

ALSO | 100 national park trip ideas, tips and photo ops »

I prefer nearby Hellhole Canyon, more strenuous and nearly six miles long, but with fewer people. It also leads to a seasonal waterfall surrounded by ferns. You can enjoy an array of plant life along the way.

Park botanist Larry Hendrickson told me there are 1,000 varieties of plants in Anza-Borrego; 100 are considered rare. As for cactuses, he said, the park has 18 species.

I continued up the sandy trail, admiring colonies of towering ocotillos guarded by cruelly misnamed teddy bear chollas whose “fur” consists of needle-sharp spines.

Fan palms appeared along a small stream. Ancient grinding holes, or morteros, used by early inhabitants to crush mesquite beans and nuts, dotted the rocks.

As I wound down through the canyon, I nearly stepped on a 20-inch rosy boa strung out along the trail. This docile snake, gray with pinkish stripes, kills small rodents through constriction.

Unlike the sluggish boas, desert iguanas repeatedly burst from the brush. The sleek, long-tailed lizards ran so fast they nearly glided over the sand.

The canopy thickened and the creek grew wider. I followed it to a waterfall tumbling into a clear pool. After lingering in the cool darkness, I reluctantly retraced my footsteps back to the car.

Into town: Borrego Springs

The town of Borrego Springs is an island amid the park. There are a few hotels, restaurants, grocery stores and an ice cream parlor. I bought a soda and drove the backstreets.

Something caught my eye.

An enormous scorpion squared off against a giant cricket in the distance like something out of a 1970s sci-fi movie.

I drove over to take a better look. The creatures were made of rusty-red metal plates. A woman posed on top of the scorpion as her husband furiously photographed. Probably not good for the sculpture.

A herd of prehistoric pachyderms charged a few hundred yards behind. Dinosaurs preened in the distance. Most stunning of all was a 350-foot-long serpent threading its way through the sand.

Cars screeched to a halt, disgorging passengers eager to see it.

The menagerie was created by Ricardo Breceda, who works out of Aguanga, Calif. The late Borrego Springs landowner Dennis Avery commissioned about 130 sculptures on property he owned throughout the town.

As I explored, I spotted a giant eagle, a family of tortoises, a bust of an Indian chief and a camel.

Quiz | How many national parks have you visited? »

Much of this art seems inspired by Anza-Borrego’s prehistoric past, a past so deep it has its own paleontologist — Lyndon Murray.

I met Murray at park headquarters. He led me to a back room where volunteers were doing 3-D photography of a prehistoric tortoise.

Murray runs a small army of volunteers who find, unearth, clean and catalog thousands of fossils. Many are displayed at the park visitor center.

Murray told me that 20% of Anza-Borrego is made up of badlands, where sediment was deposited between 1 million and 8 million years ago.

Those sediments have yielded fossil sharks, walruses, saber-toothed cats, short-faced bears, eight species of camels and giant ground sloths.

He showed me drawers full of fossils that included sea urchin skeletons and ancient horse teeth.

“Once a month we pick an area and work our way through it,” he said.

The park also runs an online education program for students throughout California. Working from a small studio, state park interpreter LuAnn Thompson does a live Internet class teaching schoolchildren about how science ties into Anza-Borrego.

“We are trying to create a connection between the kids and our state parks,” she said.

Thompson, a former high school science teacher, moved here in 2004 from Olympia, Wash., to get some sun.

“I had a guy tell me that he couldn’t understand why anyone would want to live here,” she said. “I told him that not everyone loves the city, the traffic and all of the stress.

“This place offers a real chance to be outdoors, a real chance to reconnect with nature and yourself.”

You can have solitude where you see no people at all. You can pitch a tent and hang out wherever you want.

She suggested I do a hike in Culp Valley.

I drove up the steep Montezuma Valley Road, pulled off and headed up the California Riding and Hiking Trail. It was late afternoon, cool and breezy.

I eventually reached an overlook. Hellhole Canyon, with its ribbon of green, lay far below. Borrego Springs and its metal monsters were there too.

Far beyond, the Salton Sea shimmered blue along its desolate shores.

I looked down and found a single red wildflower at my feet.

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

Anza-Borrego is California’s largest state park, but it’s not close to anything. From Los Angeles it’s a three-hour drive and from San Diego it’s two hours.

I like taking California 78 through Julian, which is a pretty drive through small towns and rural countryside before plunging down into Borrego Springs.

You can also come on California 79 through Temecula, which drops you right near the park entrance in the town of Borrego Springs. There is no park entrance fee.

WHEN TO GO

Anza-Borrego is similar to Death Valley when it comes to intense summer heat. If you crave that kind of experience, be sure to wear a hat and carry enough water to see you through your trip.

Otherwise, spring, winter and fall are the pleasantest times to visit, culminating in the wildflower bloom.

Anza-Borrego has three developed campgrounds. These include Palm Canyon near the visitor center, Tamarisk Grove and the Vern Whitaker Horse Camp. There is also a small campground at Bow Willow. For campground reservations, (800) 444-7275 or go to www.reserveamerica.com.

There are nine primitive campgrounds. Backcountry camping is allowed throughout the park. All vehicles must be highway legal and remain on established roads. Ground fires are not permitted, nor are firearms or fireworks. You are responsible for packing out any trash or waste you create.

WHERE TO STAY

I failed to reserve early and didn’t find a hotel in Borrego Springs. Don’t be like me. Here are some options.

The upper end includes Borrego Valley Inn, 405 Palm Canyon Drive, Borrego Springs; (760) 767-0311. Fifteen individually decorated rooms and two outdoor pools within a mile of the park. Doubles from $235 a night.

Borrego Springs Resort Golf Club & Spa, 1112 Tilting T Drive, Borrego Springs; (760) 767-5700. Golf to go with your desert hiking. Doubles from $119 a night.

La Casa del Zorro Desert Resort & Spa, 3845 Yaqui Pass Road, Borrego Springs; (760) 767-0100. Luxurious desert resort with 48 rooms and 19 casitas spread over its 42-acre site. Doubles from $145 a night.

Stanlunds Inn and Suites, 2771 Borrego Springs Road, Borrego Springs; (866) 430-2692. Doubles from $95 a night.

The Palms Hotel 2220 Hoberg Road, Borrego Springs; (760) 767-7788. Doubles from $149 a night, including breakfast.

Hiking and other recreation

For details on hiking and other recreation in the park, check out Anza-Borrego park magazine here or the park website. Hellhole Canyon sits just outside the main entrance to the park and is a good alternative to Borrego Palm Canyon if you want solitude. It is nearly six miles round trip, travels through different oases and ends at a 20-foot-tall seasonal waterfall.

Palm Canyon is 3¼ miles round trip through classic Colorado Desert terrain, leading to a waterfall depending on the time of year.

I have encountered lots of bighorn sheep there. Alcoholic Pass is a 1.7 mile out and back hike that is a bit steep but rewarding.

Culp Valley is at a higher elevation off Montezuma Road a few miles from the visitor center. It’s cooler and offers spectacular views of the valley floor.

The 1.8-mile Pictograph Trail in Little Blair Valley is a good place to see pictographs from the Kumeyaay people who once lived there. The trail ends at the edge of a dry waterfall overlooking the Carrizo Valley.

Lead photo: A locust pauses beside driftwood on the cracked-mud surface of Clark Dry Lake.

ALSO

Photos | Super Bloom at Anza-Borrego

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.