Discover our desert national parks and rediscover yourself. You can start with Joshua Tree

- Share via

Discover our desert national parks and rediscover yourself. You can start with Joshua Tree

Reporting from JOSHUA TREE NATIONAL PARK, Calif.

The lure of the desert is as complex as the arid landscape itself. It’s a place of revelation and escape, a parched world offering rare solitude and unexpected beauty.

But more than anything, it’s a vast expanse of rock and sky where the elemental powers of heat, light and wind run free. And for those of us in the West, it’s never far away.

North America is home to four major deserts. The sprawling Chihuahuan Desert stretches through Arizona, New Mexico and Texas before turning south into Mexico. The Sonoran Desert, the wettest and most biologically diverse, takes in swaths of Southern California, Arizona and Baja California.

About the series:

The 411 units of the National Park Service are as varied as the United States itself and an incredible legacy for Americans. The Los Angeles Times Travel section continues a yearlong look at some of those units, why they matter and how the park service is working to tell this country’s story. More in the series »

The Mojave, where broad sandy basins meet soaring mountains in California, is the smallest and driest desert. And the Great Basin Desert, spreading through Nevada, Utah, eastern California and Idaho, is the coldest.

Within these harsh and varied landscapes are dozens of national parks hosting unique plants, animals and geology.

Like botany? Visit Saguaro National Park in Arizona in spring to see the blooming saguaro cactuses. Bizarre geology? Try Devil’s Golf Course in California's Death Valley National Park. Spectacular pictographs? Hike to the Holy Ghost Panel in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park. Desert snow? Go to Great Basin National Park in Nevada.

“In the early years of the National Park Service, there was a national bias toward thinking of parks as landscapes with trees, meadows, lakes and mountains,” said Mike Reynolds, superintendent of Death Valley. “Slowly that attitude has changed.”

We are increasingly drawn to desert destinations. They are among the few places where we can sit, listen and hear something we didn’t expect: nothing. And that’s something.

“A friend took me camping in Joshua Tree National Park years ago, and as soon as I got out of my car I felt this irresistible pull to stillness,” said Darren Main, who leads meditation trips to the park every year. “It forced my mind into quiet almost instantly. It is a metaphor for what we try to achieve in yoga — becoming empty.”

Perhaps the need to disconnect from an overly connected world is behind the surge in visitors to desert parks.

Joshua Tree National Park had 2 million visitors in 2015, a record, and expects 2.4 million this year. Death Valley had 1.1 million visitors last year, the most in more than a decade. In March, 213,212 people came through its gates — 60% more than in any single month in park history.

Deserts weren’t always as popular. For thousands of years they suffered a major image problem.

Even great faiths born in the desert — Judaism, Christianity, Islam — often saw them more as hostile wilderness or crucibles for prophets and peoples than a nice place for a hike.

Satan didn’t tempt Jesus at the beach; he did it in the desert. When Yahweh punished the Israelites, he didn’t send them for a stroll in an alpine meadow; he marched them around the scorching Sinai for 40 years.

The desert is a powerful, transformative place that has laid the foundations for many of our ideas of law and justice while inspiring some of history’s greatest literature.

In fact, "desert" may be one of the oldest words in the world, according to UC Davis history professor Diana K. Davis. In her book, "The Arid Lands," she said "desert" may come from the Egyptian hieroglyph pronounced "tesert," which became the Latin deserere, meaning to abandon and forsake, before becoming the "desert" we know today.

Call it what you will; just don’t call it barren.

“That’s the perception of people from overly green places,” said Frazier Haney, conservation director of the Mojave Desert Land Trust in Joshua Tree, dedicated to acquiring and protecting desert places. “It’s all about looking closely.”

Haney hails from chlorophyll-rich Indiana, but he has put his verdant past behind him. Last Thanksgiving he wrapped a turkey in six layers of foil and buried it with hot charcoal in Mojave National Preserve . Five hours later it was done.

“Best turkey I ever ate,” he said.

As tough as deserts are, they are also fragile. Some scientists estimate that climate change could kill all the Joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park in as little as 50 years.

Panamint dudleya, also called live-forever, is a perennial succulent that can be found in Joshua Tree National Park.

“You now see grass between Joshua trees, and that grass allows fire to spread from tree to tree,” Haney said. “They don’t do well in fire. They can recover somewhat, but after a few times they’re gone.”

The famously twisted member of the yucca family also requires a deep freeze in winter for its seeds to emerge from its pods. That’s hard to do when it’s getting hotter.

And deserts don’t just sit there. Their ecosystems absorb carbon dioxide from the air like a big sponge, helping reduce one of the primary agents of climate change.

Danielle Segura, who heads the land trust, has been smitten with the desert since childhood when she witnessed a tarantula migration outside Amboy, Calif.

As we walked, she spied a desert mariposa lily, a single orange flower emerging from the sand. Fragile yet tough. Soon we were all ogling purple delphiniums, bag bushes and cactus blooms. Madena Asbell, who is creating a seed bank of local plants for the trust, swooned over flowers smaller than a match head.

Desert life is nuanced. Not big and bold, but small and tough. Even the soil is alive with layers of algae, lichens, microfungi and bacteria known as cryptobiotic crust.

“This is a unique landscape right up there with rain forests and coral reefs,” Segura said. “The desert is really a model of how we need to live. It uses all of its resources wisely, can sustain itself efficiently and is adaptable.”

It’s also generous.

When the stress of daily life snuffs out our spiritual pilot light, the desert can reignite it.

Just sit, be still and listen.

Listen to the desert

Renowned climber David Plumb Griffith III, "D.Griff" to his friends, breezed past me and began scaling a 100-foot-high granite wall free-handed.

We were at the Cyclops, a popular climbing spot in Joshua Tree named for a hole resembling a monstrous eye.

The bare-chested D.Griff reached the top in six minutes before returning to escort me up the back way, where we looked out over a sea of yuccas marching toward sunset.

“Modern man is super craving a connection with nature,” he said, adjusting his blond ponytail beneath his hat. “You come here, and it’s all about feeling the wind, the sun and it's gratifying, man. It’s magical. It’s super unreal.”

And I was super stoked to be sitting with a guy who had conquered rock faces from Patagonia to El Capitan. Better yet, he was a dude extraordinaire, a surfer-cum-climber-cum-desert rat with an engaging philosophical bent. The Dao of D. Griff.

“Dude, talk about yoga. Climb here and you connect with nature in a very intimate way,” he said. “Talk about focus and being in the moment. It’s easy to get into that meditative state here.”

More and more people are craving that Joshua Tree state of mind. Hikers, climbers and seekers of all sorts are converging on this park like never before.

Last year visitation topped 2 million, a record, and is expected to hit 2.4 million this year.

“For the past five years the National Park Service has been telling people to go out, and find their parks and it looks like they have,” said David Smith, superintendent of Joshua Tree.

Smith struggles to preserve the park while making it inviting to the public.

“The desert has a religious nature to it — the austerity, the intense heat, all the people free to contemplate their lives and roles in it,” he said. “When you are on a boulder and the wind is whipping, you begin asking yourself questions like, 'Why am I here?’”

I was here in April seeking those who find inspiration, solace and adventure in the park. And I was bowled over by the spontaneous eloquence the harsh landscape evoked, how the alchemy of wind, heat and sky could be so transformative.

The desert has a religious nature to it — the austerity, the intense heat, all the people free to contemplate their lives and roles in it.

— Joshua Tree Superintendent David Smith

Catherine Svehla, who does a podcast called "Myth in the Mojave," moved here from Los Angeles in 2001 to see how the desert would change her.

“I like that I can’t insulate myself from the natural world here,” she said as we hiked the Maze Loop. “I feel I’m a collaborator and participant in this place in a way I wasn’t when I lived in cities.”

We chose a spot among the boulders and listened to the wind — sometimes a still, small voice, other times a roaring dragon.

“We come into the desert to glory in our puniness,” she said. “There are limitations here that you simply can’t get around. And limitations are greatly underrated.”

It rained that afternoon. Lightning danced across the sky, illuminating the black clouds. The sun battled through in time to bathe the desert in stunning pink, orange and lavender light.

Rock 'n' roll heaven

That night at the Joshua Tree Inn, up the road from the park, I met a young musician in the sandy courtyard.

Charlie Salvidge is a drummer in the English rock band Toy. He and his girlfriend, Karin Johansson, flew in from London to stay in Room 8 before heading to Buck Owens' Crystal Palace in Bakersfield.

In 1973, Gram Parsons of the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers died of a tequila and morphine overdose in that room. Now it’s something of a shrine. An oversize stone guitar outside the door marks a makeshift memorial to the late musician.

"Gram Parsons had quite a big influence on me," Salvidge said. "I stayed here because I wanted more connection with him. When I walked into the room I felt sort of nervous. You realize someone died in here. It's very transcendental."

The rock 'n' roll history of Joshua Tree runs deep, thanks to its proximity to Los Angeles.

Park spokesman George Land, a former concert promoter, is an expert on the subject. He’s also a fast-talking raconteur with hints of Don Rickles.

He hopped into my car.

“Do you always keep it so cold in here?” he asked.

“It’s hot outside,” I protested.

“You could hang meat in here!” he retorted.

I turned down the air.

As we drove through the park, Land told me about Magic Mountain, where musicians, celebrities and others ate peyote. He produced a picture of an Eagles album showing the band around a campfire in the park. I was saddened to learn the Joshua tree on the cover of U2’s "The Joshua Tree" album was not in the park but near Death Valley. And it’s dead.

We stopped at Cap Rock, where Parsons was cremated, an event that has passed into rock legend.

Parsons’ producer Phil Kaufman, believing he was fulfilling his friend’s dying wish, stole his body. He and an accomplice bought a 5-gallon can of gas, a case of beer and drove to Cap Rock.

“If you’re going to cremate your best friend, you’re going to need beer,” Land said. “It’s thirsty work.”

They toasted Parsons, then torched him.

“The body smoldered until the next morning,” Land said.

'An unexpected gift'

We headed to Keys View, where on a clear day you can see Mt. Signal in Mexico.

Jürgen Schimmelpfennig was leaning on leg braces and gazing over the desert. He had kind eyes and a deeply lined face.

For years the biology teacher from Germany has made desert documentaries with his wife. The natural history of the coyote and saguaro cactus were especially popular on German TV.

“We have had a great life and now, if it’s a little shorter in the end, we ask ourselves, 'What else could we have wished for?'" he said.

I dropped off Land, and he slipped me a handful of commemorative Joshua Tree guitar picks. Then I hiked down the Pine City trail among hedgehog cactuses sporting brilliant purple flowers.

Winter rains had sparked impressive blooms throughout the park. Plants that slink through life with little fanfare adorned themselves in resplendent reds, pinks and ochers. It reminded me of high school prom, where tuxedos and glittery dresses made even the awkward and homely briefly beautiful.

The fauna was plentiful. Bighorn sheep lingered by the road. Coyotes darted through the brush and horned toads stalked ants in sandy washes.

Artist Karine Swenson knows this world well. She spends mornings hunting wildlife with her camera. Once they are photographed, she paints their portraits in her studio. Jackrabbits are her favorite.

I joined her at the Hidden Valley Nature Trail.

Swenson grew up in South Dakota and made frequent car journeys to California, hating the "hot, horrible desert" every time she crossed it. When her husband was transferred to Southern California, they moved to the community of Joshua Tree.

“Now I love the desert," she said. "I love the heat. In summer the light lasts forever.

"The desert has been an unexpected gift.”

It was lunchtime, so I made for the Crossroads Cafe just outside the park entrance.

Levon Kazarian, its co-owner, joined me.

Business is so good these days, he yearns for competition.

“We have to tell people it will be an hour for a table; we run out of menu items,” he said. “We are a tiny restaurant punching way above its weight.”

I asked whether he considered himself a desert rat.

“Right now,” he said, laughing, “I’m still just a poser.”

'It's all an adventure'

That night I went walking with Ken Layne, publisher of the Desert Oracle, a slender gem of a field guide packed with folklore, freaks and general musings on the glories and weirdness of the desert.

Curious about the Yucca Man? Marvin of the Mojave, a ghost with size 10 sneakers? Ringtails? Buy the Oracle.

“The desert has suddenly become cool,” Layne said, as a quail burst out of the brush. “The millennials think it’s authentic. They come on their way to and from Coachella; it’s become something you have to do.”

For years the high desert was known more for its sketchy characters than the hipsters; the empty wilderness often was seen as less a place to preserve than somewhere to toss your old sofa.

Layne prefers the newcomers in some ways.

“It’s a much better problem to have than living in a place where almost everyone is aggressively hostile to the environment,” he said. “Let Joshua Tree have its moment.”

Back at the Cyclops, I met Seth Zaharias, who runs Cliffhanger Guides with his wife, Sabra Purdy.

Zaharias worries about the surge in visitors. He finds toilet paper behind rocks, graffiti and increasingly scarce parking.

“It’s an interesting conundrum,” he said. “I have more money in my pocket than ever before, but my quality of life has plummeted.”

Ropes tied, Zaharias and Purdy began climbing.

“It’s still the greatest hang ever,” he said.

D. Griff offered color commentary from the summit.

“You can do your little victory dance at the top or fall and bleed out on the rocks,” he said, puffing on a stubby cigarette. “It’s all an adventure, man.”

I realized then I could listen to D. Griff all day.

As for the crowds, he offered this:

“If you want solitude just walk 15 minutes into the desert, sit there and look at a rabbit,” he explained. “That’s it.”

“That’s it?” I asked.

“Listen, I surf and do other sports, but it’s all the same thing, an excuse to be out here. You take what you can from this and go back to your world,” he said. “Go out to the desert, sit down and listen. Then go home.”

And that’s it.

If you go to Joshua Tree National Park

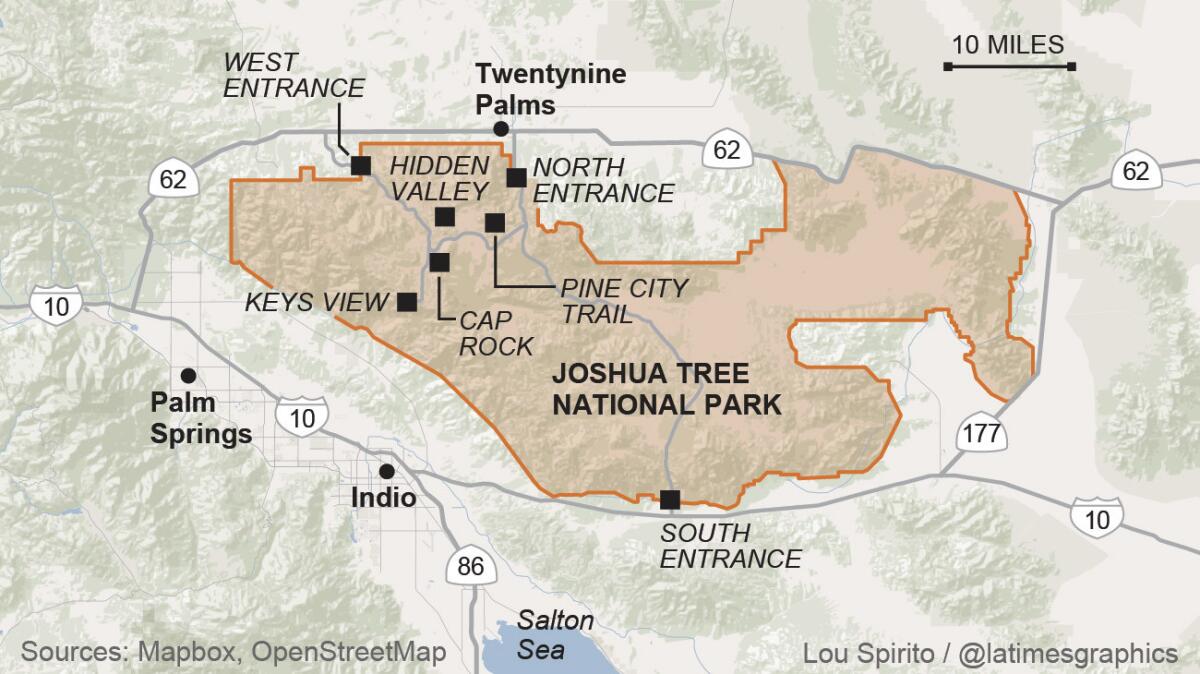

Getting here: Joshua Tree National Park is about 130 miles east of Los Angeles. Take Interstate 10 east to Exit 117 to Highway 62. The road leads to the park entrance in the community of Joshua Tree; you can drive farther and reach another entrance in Twentynine Palms.

Cost: The $20 fee covers a seven-day non-commercial vehicle permit. It's $10 for motorcycles or bicycles and for each person on foot.

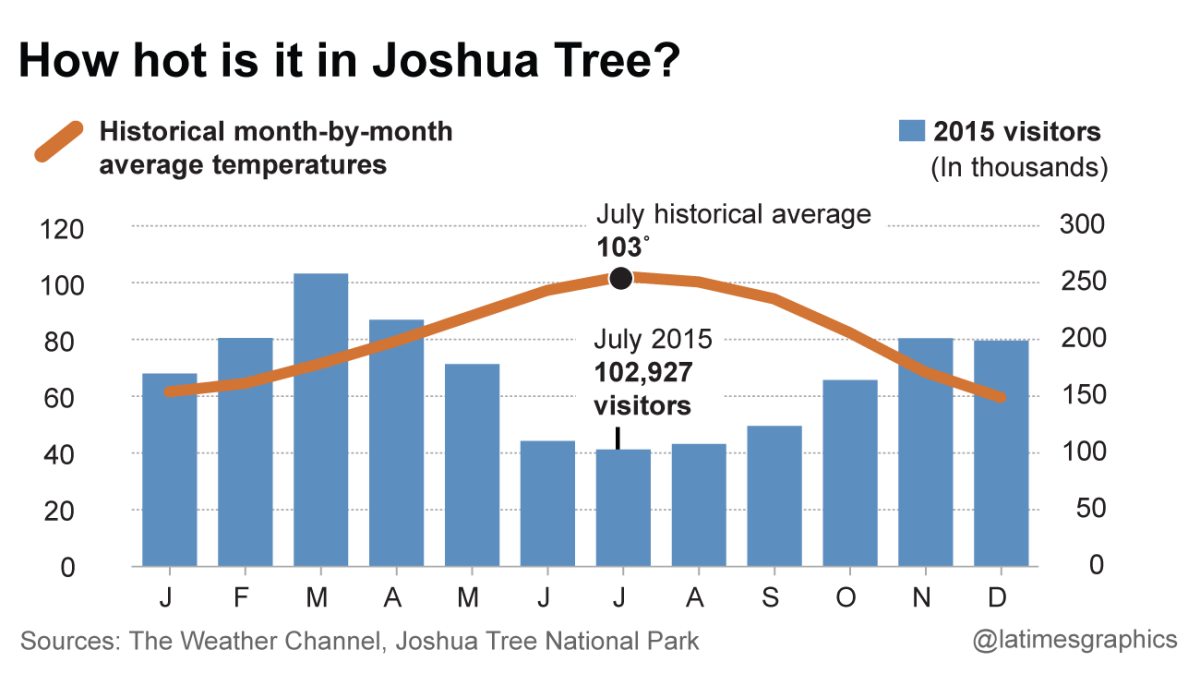

Best time to visit: Temperatures are most comfortable in the spring and fall, with an average high of 85 degrees. Winter days are cooler, about 60 degrees. Summers are hot, with temperatures topping 100 degrees.

How to visit: The desert can be life-threatening. Drink at least one gallon of water a day to replace loss from sweat. Potable water is available at only a few locations around the park boundaries, so you must bring the water you need.

Accessibility: Park visitor centers and certain nature trail and campsites comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act requirements.

Sleep: There are nine campgrounds in the park, which usually fill on weekends from October through May. Most are on a first-come, first-served basis, but you can reserve camp sites at several. $15 per site, per night at campgrounds without water; $20 at sites with potable water in or near the campground. I stayed at the Joshua Tree Inn, 61259 Twentynine Palms Highway, Joshua Tree; (760) 366-1188. Comfortable, colorful place full of art and history. (Room 8 is where rocker Gram Parson died of an overdose in 1973.) It sells out quickly. Rooms from $89 a night.

Eat: There are plenty of places for a good lunch or dinner in the town of Joshua Tree. Crossroads Café, 61715 Twentynine Palms Highway, Joshua Tree; (760) 366-5414. Excellent choice for great-tasting casual fare at reasonable prices.

Entertainment: Pappy & Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace, 53688 Pioneertown Road, Pioneertown, Calif.; (760) 365-5956. Legendary for its live music. If you want a drink closer to the park, try the Joshua Tree Saloon, 61835 Twentynine Palms Highway, Joshua Tree; (760) 366-2250.

More info: Check the Joshua Tree National Park website to find out about activities at the park, including hikes led by Superintendent David Smith. If you have a chance to talk to park spokesman George Land, take it. Break the ice by asking about the can of spotted dick – a British sponge pudding - on his desk.

Follow our adventures: Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

Additional Credits: Digital design and production: Sean Greene.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.