The magic of Klickitat Street

- Share via

We were driving through the gracious old suburbs of Portland, Ore., searching for a cafe that had gotten raves for its seafood, when I looked up from my map and saw a sign that resonated to the core of my bookworm soul: “Klickitat Street.”

Those two words hurtled me through time and place back to childhood and the ragged paperbacks I reread until they became part of my psychic landscape.

Any reader worth her salt knows that Klickitat Street is where Henry Huggins and Ramona and Beezus (née Beatrice) Quimby lived in the classic children’s books by Beverly Cleary. For me, they weren’t just characters, they were real children, filled with the desires, dilemmas and annoyances that consumed my own life. I could almost hear them playing a few blocks down the street. And I longed to share their adventures.

After I grew up, I discovered Cleary all over again when I read her books to my boys. I was almost afraid to revisit them. Her first, “Henry Huggins,” came out in 1950. What if it was embarrassingly dated or no longer relevant to wired, 21st century kids? To my delight, Henry, Ramona, Beezus, Scooter and the gang were as engaging to my children’s ears as they’d been to mine. So were her other books, especially “The Mouse and the Motorcycle” trilogy, which spotlights those twin icons of boyhood -- rodents and bikes.

As we read each book aloud, I analyzed why Cleary’s writing seems as fresh today as it did a half-century ago. For starters, the writing is simple, clear and funny. Her plots revolve around elemental themes -- a birthday party, odious chores, a lost dog, a pesky little sister, the need for spending money. Lastly, there are no pyrotechnics, no irony, no local color. It could be Anywhere, USA.

You can see why I was so excited that day in Portland. “Look,” I shrieked, “it’s Klickitat Street. Where Henry and Beezus and Ramona lived.”

“We know, Mom,” said my 11-year-old, who has graduated to books about teenage spies.

“Cool,” the 9-year-old said and went back to his “Star Wars” book.

How quickly childhood’s passions fade. “Pull over, please! We’ve got to get a picture,” I begged my husband, who long ago learned to indulge my literary fantasies.

We got out, and I studied the lovely old houses with their gables and porches, the tall shade trees and the pleasantly overgrown yards. Which house was Henry’s? What about his grumpy neighbor, Mr. Grumby? Where was the vacant lot where the kids found discarded boxes of bubble gum to sell at school? (Clearly a more innocent time.) Could that mutt be Ribsy’s great-great-grandson?

As a child, I’d studied the back of the Newbery Medal winner’s books with Talmudic intensity, trying to imagine Ribsy and Ramona’s creator from the scant biographical information and the photo of a pretty, prim, pleasant, dark-haired lady who’d been a children’s librarian. But she remained as remote to me as God.

On Klickitat Street, I pictured Cleary in an upstairs bedroom with a notebook on her lap, biting a pencil and staring out at the rain. This was the fount, the touchstone. From here, an entire world had sprung!

Four blocks away, we found Grant Park, a leafy, inviting place with swings, slides and merry-go-rounds. Could this be where Henry caught 1,000 night crawlers to sell to fishermen? Where the Woofies Dog Food Co. had awarded Ribsy a trophy for Most Unusual Dog?

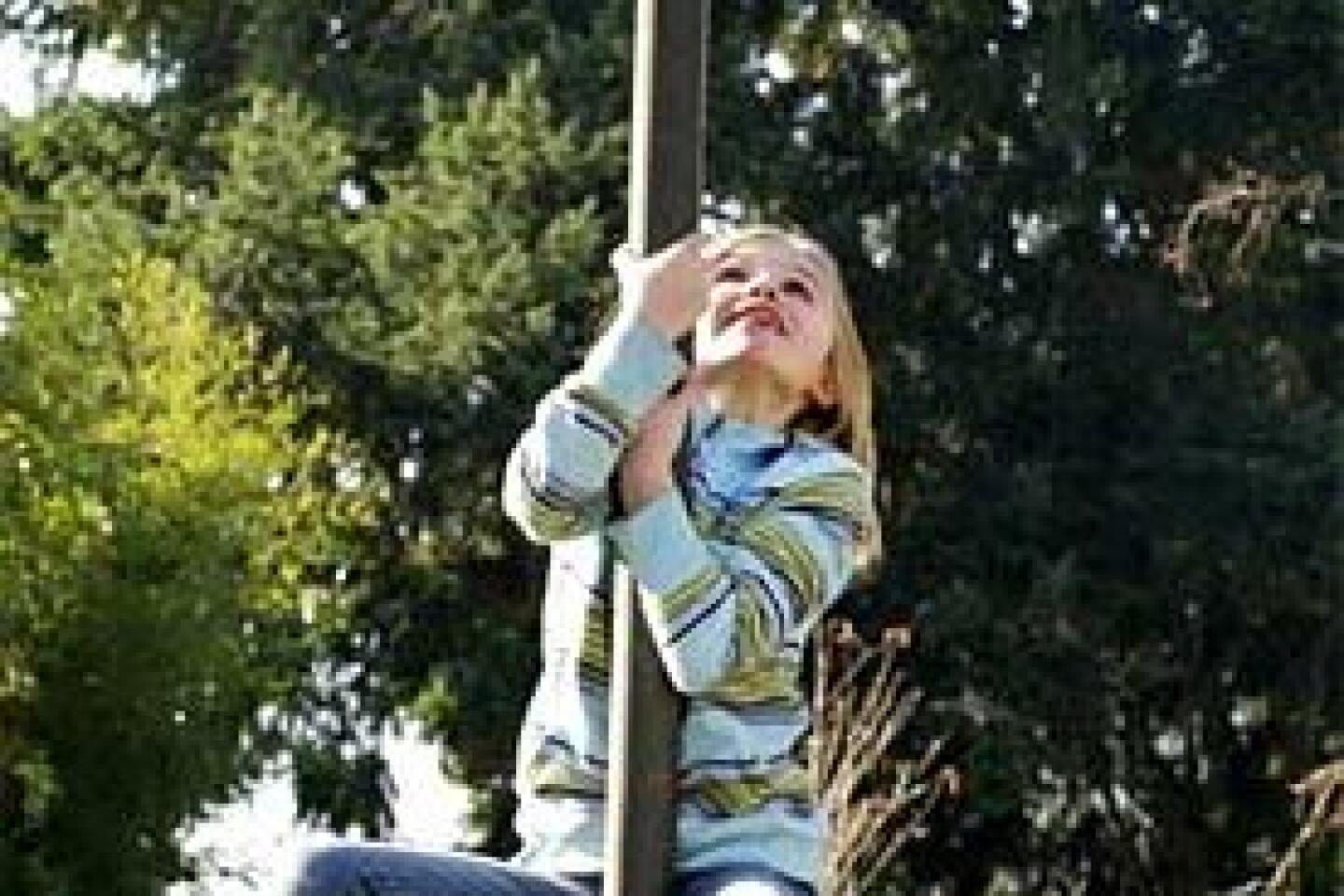

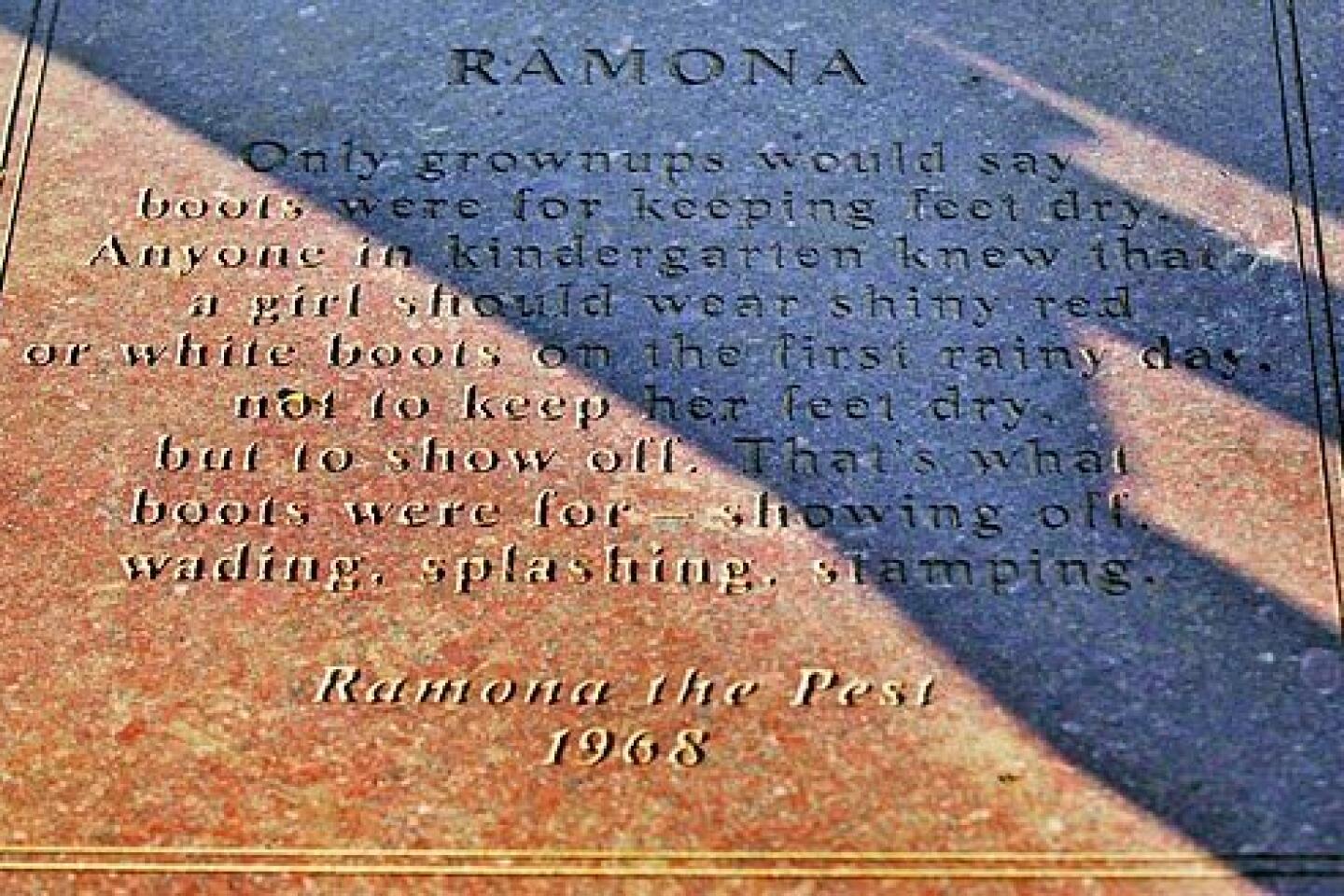

My husband discovered a fountain and sculpture garden and called me over. As twilight fell, I beheld bronze statues of a boy, a little girl in rain gear and a dog. They looked somehow . . . familiar. Reading the plaque, I laughed in disbelief. With the serendipity that life sometimes bestows, we’d wandered into the Beverly Cleary Sculpture Garden. It’s a magical place, with quotes on granite tiles from her most famous books. The sculpted figures by local artist Lee Hunt capture Cleary’s characters in all their pesky, kinetic glory.

It hadn’t even been listed in the guidebook!

I was surprised and delighted to learn that Cleary is still alive. She’s 91 and lives in Carmel. Oddly, only her “Ralph Mouse” series has made it to TV. Can Hollywood be immune to the simple joys of Klickitat Street?

Cleary has written two candid memoirs -- “A Girl From Yamhill” and “My Own Two Feet” -- filled with quiet wisdom. Born in 1916 on a farm in Yamhill, Ore., Beverly Bunn moved to Portland as a child. Although she lived several blocks away, on 37th Street, she’d always liked the name Klickitat Street.

Avid “Ramona” fans will recognize details from Cleary’s childhood: In elementary school, Cleary was puzzled by the song lyrics, “the dawnzer lee light”; her father lost his job during the Great Depression; she was teased for naming her doll Fordson-Lafayette after a tractor. (Ramona calls her doll Chevrolet, “the most beautiful name in the world.”) Her love of writing was sparked on a rainy weekend in seventh grade when she wrote a short story as an assignment: “To this day whenever it rains I feel the urge to write.” One anecdote that didn’t make its way into the children’s books: Cleary’s escape from a pedophilic uncle.

Cleary writes movingly about her determination to attend college and learn a profession (at a time when most young women did neither) and of her hunger to write for reluctant readers, the kids who “built scooters out of apple boxes and roller skates.”

Perhaps the biggest surprise was that Cleary had lived in Southern California with her aunt’s family to attend Chaffey Junior College in Ontario from 1934 to 1936 because California colleges offered free tuition to residents. She writes lyrically about sunshine, palm trees, avocados, orange groves and tanned, easygoing Californians she met here, where the Depression didn’t seem nearly as crushing. She earned degrees in English from UC Berkeley and librarianship from the University of Washington, then became a children’s librarian in Yakima, Wash. (The L.A. Public Library also offered a job, but Cleary lacked the bus money to travel for an interview.) In 1940, she married college sweetheart Clarence T. Cleary, and they settled in the Berkeley hills, where she wrote “Spareribs and Henry,” a story she expanded into her first book, after renaming the dog “Ribsy.”

A renowned children’s book editor at William Morrow bought “Henry Huggins” in 1949 for $500, asked for revisions and assured Cleary that “we all think this is going to be one of the exciting publications of the fall.”

Prophetic words: Cleary’s career spanned half a century. Her last, “Ramona’s World,” came out in 1999.

In her memoirs, Cleary writes that she never outlined, ignored all trends and tried to remember her mother’s admonition to “keep it funny.”

“Even though I was uncertain about writing, I knew how to tell a story. What was writing for children but written storytelling?”

Denise Hamilton is the editor of “Los Angeles Noir” and writes the Eve Diamond crime novels.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.