Cuba feels the pinch of the Trump administration’s travel restrictions

- Share via

HAVANA — When a bus packed with Spanish tourists pulled into her restaurant in the picturesque Viñales Valley in mid-July, Rosa Isabel Hernandez Pino was grateful. But she was also worried.

That busload represented her last reservation for the summer. Americans aboard cruise ships that docked in Havana used to account for the bulk of her business. But on June 4, the Trump administration announced that Americans could no longer travel to Cuba on cruise ships, and also eliminated a category of travel called people-to-people group tours.

For the record:

2:23 p.m. Aug. 12, 2019An earlier version of this article misspelled Laila Chaaban’s name as Chaabon.

Reservations for Hernandez’s thatched-roof Doña Rosita’s restaurant, with views of oxen tilling fields and the limestone hills of the Viñales Valley, came via government tour agencies that paid her a negotiated rate of $15 a lunch for a home-cooked spread that included chicken, pork, yucca, rice and beans produced on the land that her family has farmed for six generations.

Hernandez and her family made a good living with the restaurant after President Obama made it far easier for Americans to travel to Cuba in 2015. The Trump administration began chipping away at the changes , and with the newest limitations on American travel, Hernandez said, “I think I will have to go out of business.”

Cuba’s fledgling private-sector workers — cab drivers, tour guides, souvenir sellers, restaurateurs, bed and breakfast operators — are already feeling the pinch.

The Trump administration contends the policy, which still allows for 11 categories of visits including for religious activities or professional research, is aimed at keeping U.S. dollars out of the hands of the Cuban military, ending what national security advisor John Bolton calls “veiled tourism.”

In a tweet the day the restrictions were announced, Bolton made clear they were also designed to punish Cuba for its support of Venezuela’s autocratic leader Nicolas Maduro: “Cuba has continued to prop up the illegitimate Maduro regime in Venezuela and will be held responsible for the man-made crisis. President Trump has made it clear that we stand with the Cuban and Venezuela people as they fight for freedom.”

Trump, in a June 2017 speech in Miami, declared his new policies toward Cuba would bypass “the military and government to help the Cuban people form businesses and pursue much better lives.”

Many Cubans say, however, that their private businesses have slowed to a crawl as many relatively free-spending Americans are removed from the visitor mix.

At Fusterlandia, where artist Jose Fuster has covered practically every inch of his home and workshop in mosaic tile and begun to cover walls, bus stops and nearby homes as well, the neighborhood on the outskirts of Havana is hurting.

As Fuster’s art installation gained fame, a cottage industry had sprung up and his neighbors began selling coconut water, pina coladas and all manner of souvenirs.

“I would say business is down 60% since the cruises stopped,” said Adrian Alberto, a vendor, as he sat forlorn on a mosaic-encrusted bench in front of Fuster’s house.

“Business is down so much you can practically weep,” echoed fellow vendor Yoan Perdomo Viort.

“This street used to be so full of tour buses and taxis you almost couldn’t walk,” he said. At 10:30 on a recent morning, only one tour bus and a few cars were parked outside.

“It’s been a very slow year,” sighed Andrea Gallina, who runs Paseo 206, a private 10-room boutique hotel in a 1930s mansion in Havana’s Vedado district, with his wife, Diana. In early 2017, Americans represented about 55% of their customers. Now, he said, they make up only about 30%.

“The Irma-Trump combination hasn’t been good,” added Gallina, an Italian who quit his job at the World Bank and came to the island with his Cuban wife in 2012 as former President Raul Castro began opening the economy to the private sector.

Hurricane Irma hit Cuba’s north coast hard in September 2017, causing widespread flooding. Even though the government and private entrepreneurs made it a priority to quickly clean up damage at tourist facilities, bookings were canceled and the storm put a damper on the 2018 winter season.

That coupled with Trump’s moves has sowed confusion, Gallina said. “In any market when you create confusion, people are reluctant to come.”

His solution: Market more and diversify his customer base to include more Europeans and Latin Americans.

“After a new regulation, people are afraid. They think it’s illegal to go to Cuba,” agreed Camilo Condis, an outspoken advocate for private entrepreneurship in Cuba.

It’s not illegal. While Americans aren’t supposed to engage in vacations devoted solely to lounging on Cuban beaches, they can still travel to the island if, according to State Department guidelines, they engage in “activities intended to enhance contact with the Cuban people, support civil society in Cuba or promote the Cuban people’s independence from Cuban authorities, and that will result in meaningful interaction between the traveler and individuals in Cuba.”

Many travelers, however, aren’t sure what that means.

“For me, tourism isn’t a good sector anymore,” said Condis, who made his living by renting an apartment to visitors and working in a private port-area Havana restaurant called El Figaro. This year, he said, revenue at the restaurant, which sits along a street where dozens of Cubans have opened private businesses, is about 10% of what it was a year ago.

Now he plans to sell the apartment, quit his restaurant job and work in construction.

Despite the Trump sanctions that have included placing a number of hotels owned by the Cuban military on a prohibited list for Americans, construction cranes tower over Havana neighborhoods near the sea, and government-owned and joint venture hotel projects are moving forward.

Once shunned by the revolutionary government as bourgeois, tourism has become one of Cuba’s most important generators of foreign exchange since the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of its subsidies to Cuba.

During the peak year of 2017, it brought in $3.2 billion.

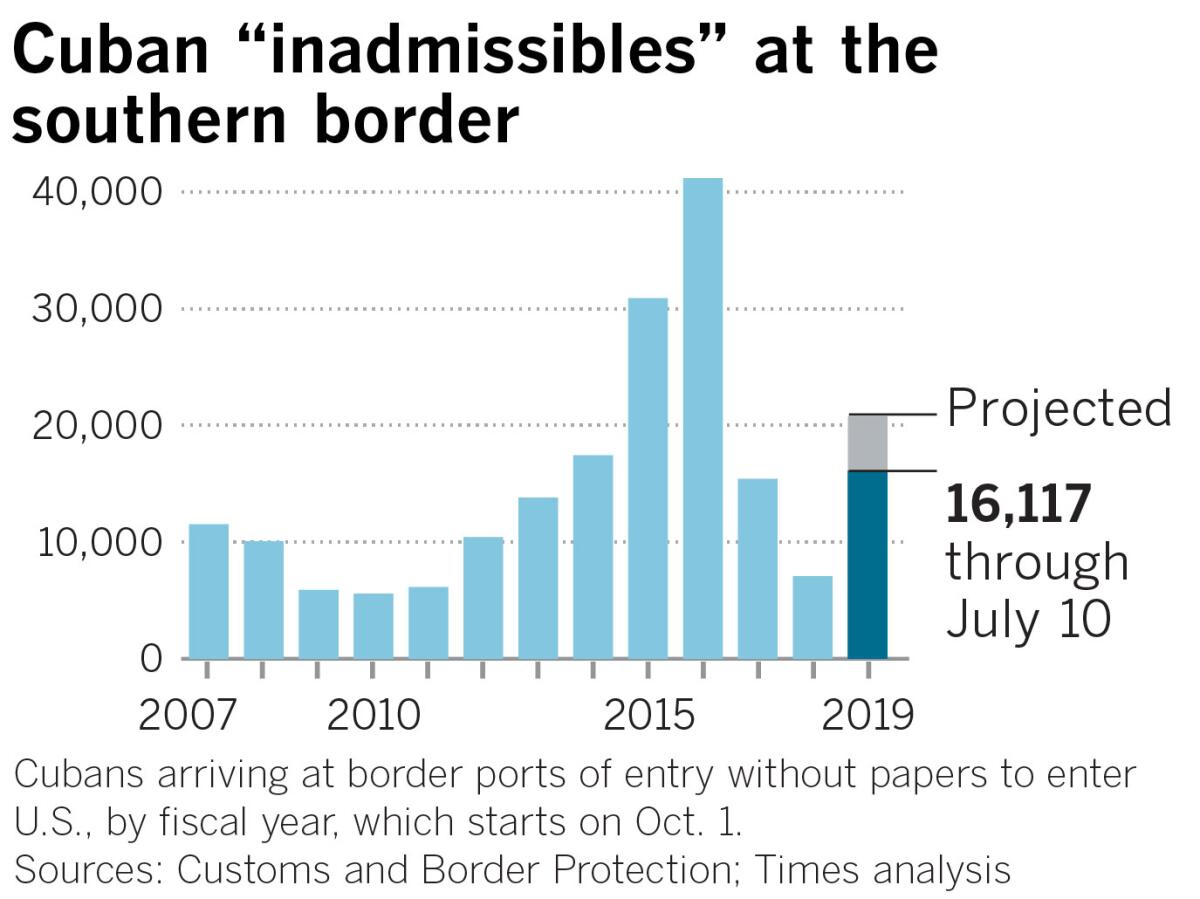

This year, 372,857 Americans visited the island by air and sea through June, ahead of last year’s 266,441, according to estimates by Cuban economist Jose Luis Perello. A surge in cruise passengers before the June restrictions accounted for much of the growth.

Perello said the change in U.S. policy meant 30,000 fewer cruise passengers visited in June alone, and the Cuban government has adjusted its goal of 5 million international visitors this year down to 4.3 million. In 2018, there were 4.7 million international visitors.

In the euphoria after the United States and Cuba reestablished diplomatic relations in 2015, many Cubans made decisions to renovate a room in their homes or buy buildings to open a business, thinking the steady stream of American visitors under the Obama administration would continue and grow.

Hernandez said her family spent around $6,000 to build the restaurant in Viñales, which is about a two-hour drive from Havana.

Laila Chaaban, a young Cuban fashion designer who opened a clothing store three months ago, also is feeling squeezed.

Chaaban had been working in a clothing factory in Ecuador, but she returned to the island in 2016 to start her own business.

But finding a building she and her mother could afford and renovating its street-facing living room for Capicua, her store, took longer than expected.

Capicua launched just before the new Trump travel sanctions. “I have some good days; other days I get panic attacks,” said Chaaban, who was wearing jeans and a flirty red top of her own creation. “The only consolation is the business is breaking even.”

But if things don’t pick up, she said, she’ll be lucky to hold on for a year.

“It’s been chaos [since the cruises ended]. It’s been tragic for a lot of people,” said freelance tour guide Zoila Alviles. “A lot of my friends who work for tour agencies haven’t worked at all this summer.”

Within days of the new travel restrictions, some private taxi drivers put their cars up for sale. Others who borrowed money to buy cars now worry about making the payments.

“In the end, it’s all sorts of Cubans who are impacted, not just the government or government officials,” said Giulio Ricci, a University of Havana economist.

Even businesses not particularly dependent on American visitors say they’ve been hit. Enrique Suarez, head chef and owner of the Tocamadera gastropub in Havana’s fashionable Miramar neighborhood, said affluent locals make up the bulk of the clientele in his 38-seat restaurant.

Many people who live in Miramar have houses or apartments for rent to visitors in Old Havana and with those earnings drying up, they are not eating out as much, he said. “They were here two or three times a week and now they’re not,” said Suarez.

Recent weeks have brought mixed news from the United States. A bipartisan group introduced legislation in the House of Representatives that would eliminate any restrictions on travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens and legal residents. It would also end prohibitions on travel-related banking transactions.

In the Senate, Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.), joined by 45 co-sponsors, introduced a Freedom for Americans to Travel to Cuba Act.

“The Trump administration’s policy toward Cuba is completely at odds with its policies toward other countries,” said Leahy. “Freedom to travel is a right. It is part of who we are as Americans.”

But the U.S. State Department has instead added to its prohibited list of Cuban businesses and organizations, including two more hotels controlled by the Cuban military.

“The department remains committed to ensuring U.S. funds do not directly support Cuba’s state security apparatus, which not only violates the human rights of the Cuban people, but also exports this repression to Venezuela to support the corrupt Maduro regime,” it said.

Whitefield is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.