Uganda’s newest attraction: Idi Amin, its dictator from the 1970s

- Share via

KAMPALA, Uganda — Four years ago, researchers working to preserve Ugandan history came across an old metal filing cabinet at the state broadcasting company and pried it open. Inside were some 70,000 negatives.

Their main subject was Idi Amin, the notorious dictator who ruled Uganda during the 1970s and oversaw the killings of as many as 300,000 people.

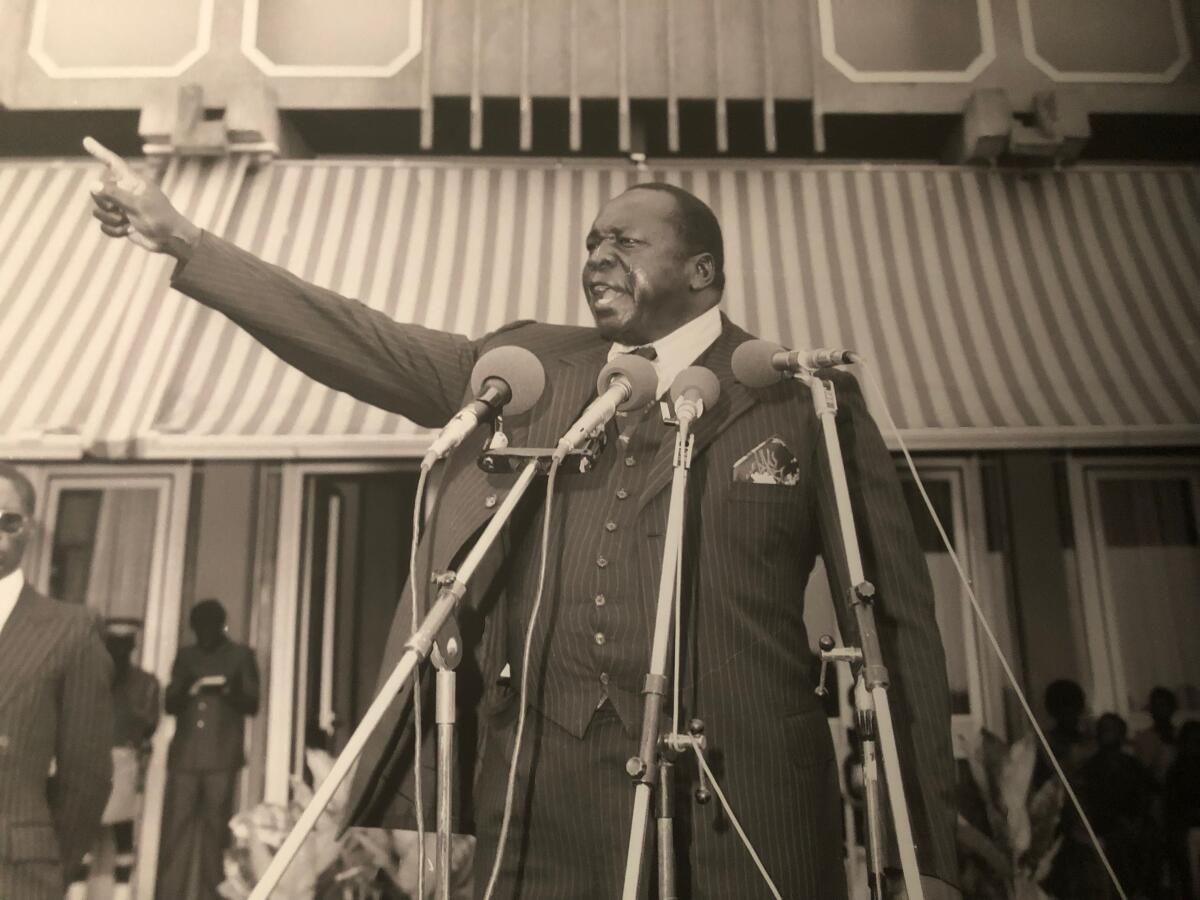

In one image, he wears an immaculate suit and stands before a cluster of microphones mid-speech with an index finger thrust into the air. He looks statesmanlike.

Now that photograph and about 200 other images taken by his official photographers are on display in the capital, Kampala, at the Uganda Museum.

The exhibition juxtaposes images of Amin with images of his victims — government ministers, soldiers, business owners, religious leaders — to achieve an effect that is both haunting and chilling.

In a place that has long tried to forget its grim past, that was the intent.

“This country has gone through tumult,” said Nelson Abiti, a curator at the museum. “We want people to open up and talk.”

The exhibition is also a rough preview of the current government’s plan to memorialize that dark chapter of Ugandan history with two permanent Amin exhibitions at the museum and the opening of a regional museum near Amin’s hometown in northwest Uganda.

Creating a permanent space about the Amin era in Kampala is a response to interest from tourists, according to Rose Mwanja Nkaale, the commissioner of the government’s Museums and Monuments department.

The Uganda Tourism Board has also been exploring the idea of tapping into the growing international “dark tourism” market.

Neighboring Rwanda, where 800,000 people were killed in a 1994 genocide, has a memorial in its capital, Kigali, where more than 250,000 victims are buried, and a wall is being built to display the names of the dead.

In Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge exterminated about 2 million people during the 1970s, tourists can visit the burial sites known as the Killing Fields as well as the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, a former high school school in Phnom Penh that the regime turned into a prison.

“We were taking lessons from Rwanda, where past tragedies can be a source of attraction,” said James Tumusiime, a book publisher and former chairman of the Uganda Tourism Board who floated the idea of an Amin-era museum when he was in office.

“Idi Amin’s name attracts a lot of interest,” he said. “He became a major selling point for Western media — his large size, his ruthlessness.”

Of course, it is also good politics for current leaders to remind voters and visitors how bad things used to be.

Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, was welcomed as a hero at home and internationally in 1986, when his guerrilla army overthrew the government and he took power.

But three decades later, he stands accused of torturing political opponents and suppressing democratic freedoms to cling to office. He recently did away with the presidential age limit of 75 — his current age — so he can run again in 2021.

Museveni and his government reject the idea that he has become a dictator.

A spokesman for the government said it has supported efforts to preserve the country’s dark past to ensure that a leader like Amin — often dubbed “the butcher of Uganda” — never returns.

“Never again shall we have a leader like that,” said the spokesman, Ofwono Opondo. “Never again shall we have a government like that.”

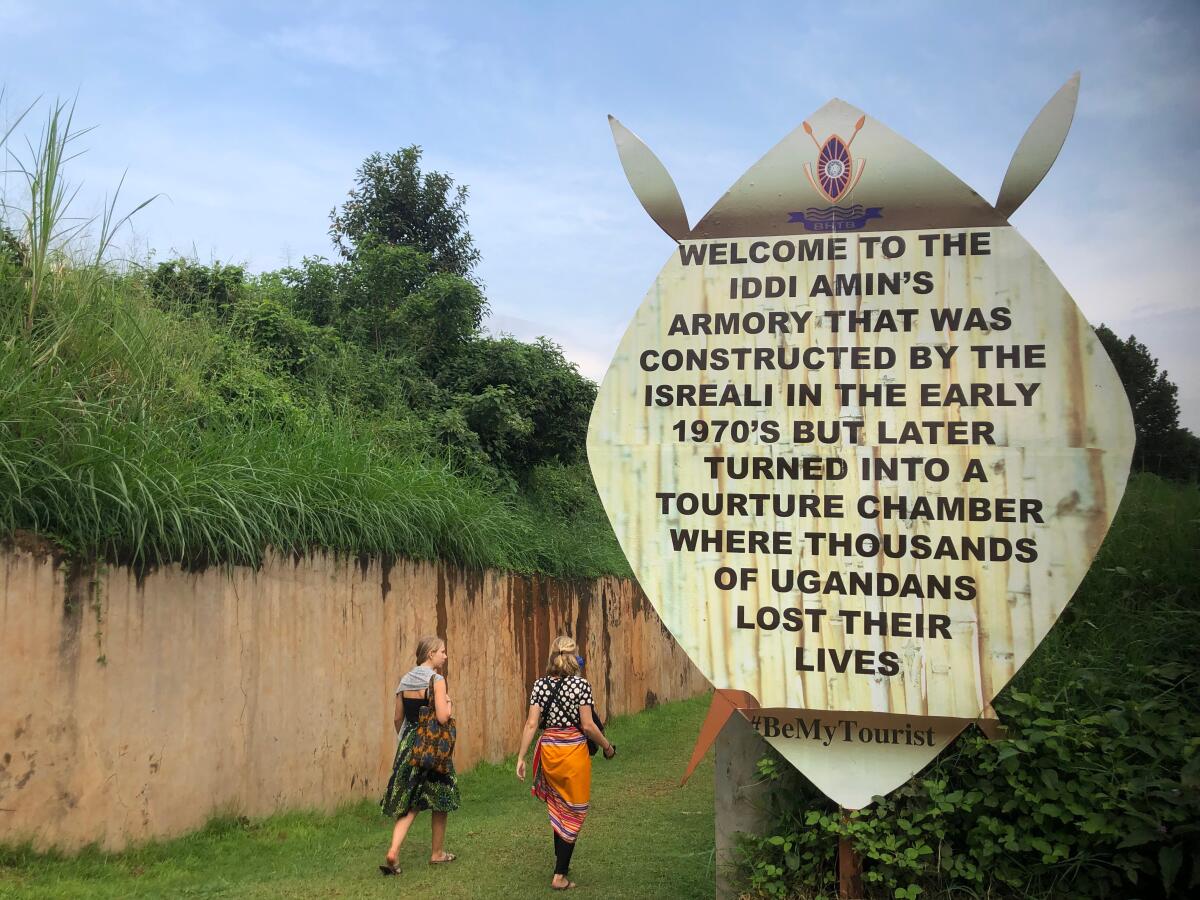

There are a few other “dark tourism” sites around Kampala, including a dank, underground bunker beneath an old palace.

Each day, guides lead small groups into a dark cement lair used by Amin’s government to torture political opponents, intellectuals, lawyers and religious leaders. Soldiers stationed there during Amin’s era estimated that as many as 25,000 people died in the bunker.

“It’s harsh, but it’s important to know,” Karen Boel, a Danish tourist, said after visiting the bunker and the photography exhibition. “... It’s not so long ago.”

The exhibition — titled “The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin” — is one of the first efforts by a public institution to tackle the dictator’s complex legacy and memorialize his victims of the era, according to its organizers.

“This is uncharted territory in many ways,” said Derek Peterson, a professor at the University of Michigan, one of the institutions that organized the exhibition. “You never know how people are going to respond.”

After the exhibition closes in Kampala at the end of November, it will move to other locations in Uganda to give people outside the capital a chance to see it.

The government is using visitor feedback to help design the permanent exhibitions. The new wing at the Uganda Museum is under construction.

The museum planned in the city of Arua — near Amin’s hometown of Koboko — is still a year or two from opening, Nkaale said.

Far from most other tourist attractions, it would cater to people in that area. The dictator is remembered fondly by some of the older generation there for directing government largesse to his own ethnic group.

Abiti, the curator, worried that actively marketing the Amin era to tourists will perpetuate the stereotype of Uganda as home of the quintessential African dictator.

“People still think Uganda is in darkness,” he said. “This country has moved on. We’re not at war.”

Some Ugandans whose families were torn apart by Amin’s policies welcome the chance for the world to learn more about those years.

“At that time, the caretakers of the world didn’t take notice,” said Sanjiv Patel, who was 7 years old when Amin forced his family to flee the country. “Uganda was really forgotten.”

“I want the world to understand that this happened. There’s nothing wrong in showing a country what happened when you support brutal leadership.”

The 1972 expulsion of nearly 80,000 Ugandans of Asian descent, whose businesses were handed out to Amin supporters, wrecked the country’s economy. Patel’s family resettled in India.

He moved back to Uganda in the early 1990s, one of tens of thousands to return after Museveni invited the families back and gave back some of their assets.

Patel now heads an agricultural supply company. He said Museveni has brought “harmony” to the country after years of upheaval.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.