GE says it’s going green. Overseas, it’s still pushing coal

- Share via

VUNG ANG, Vietnam — Since an enormous coal power plant went up five years ago near a once-empty beach, villagers here blame its emissions for the pains in their chests, the foul smell in their groundwater and the fine black dust that smears their rice crop.

Now the Vietnamese government is planning a second coal-fired plant next door, but officials have told residents little about the project, which is financed by investors from China, Japan and Singapore — and due to run on equipment from one of America’s most familiar corporate names: General Electric.

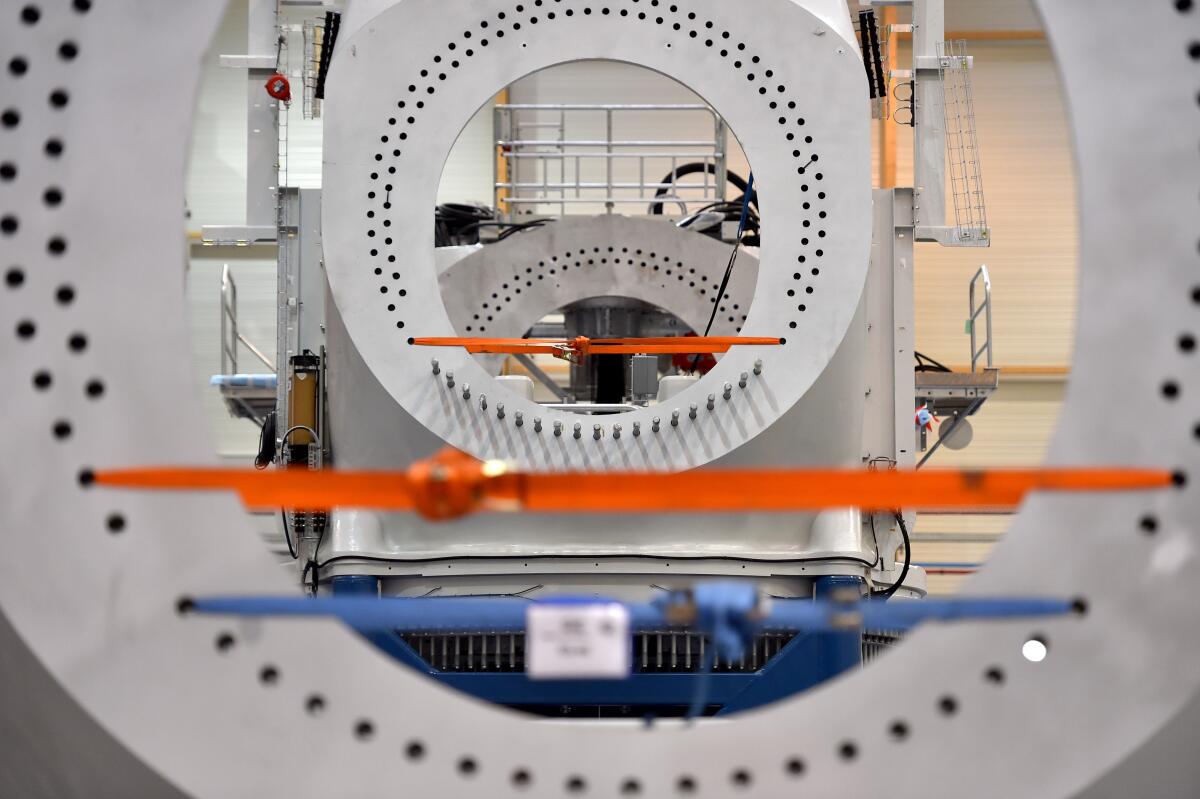

In the U.S., GE is increasingly known for wind turbines and other renewable energy technology, among many other products. But the 1,200-megawatt plant due to be built here on Vietnam’s northern coast is one of 19 coal power projects the company is working on in 17 foreign countries, many with far weaker environmental standards than the United States.

The projects have prompted allegations that GE, mired in financial trouble, is attempting to dump outdated and highly polluting technology on developing countries.

They also put GE at odds with a growing number of international banks and manufacturers that are no longer investing in new coal infrastructure because of the environmental damage caused by the dirtiest fossil fuel and the increasing affordability of solar and wind energy.

“There’s no way GE could get away with this sort of aggressive expansion of coal in the U.S.,” said Julien Vincent, executive director of Market Forces, a climate advocacy group based in Australia.

Company officials say the countries where they sell technology want coal — still the world’s No. 1 power source — to boost economic development. Vietnam’s communist government, which approves every energy project, is planning to boost its growing manufacturing sector by adding more than 33.5 gigawatts of electricity over the next decade, half of it from coal.

GE says that its coal plants are more environmentally friendly than the global average, and that it has upgraded the design of several projects, including the northern Vietnamese plant dubbed Vung Ang 2, to reduce carbon emissions.

“We support customers and governments who are working to deliver access to affordable and reliable electricity,” GE said in a statement to The Times. “GE provides the best available technology, no matter which fuel is chosen.”

Environmental groups argue that coal plants pollute poor communities, and that any expansion of fossil fuel-based power jeopardizes efforts under the Paris climate agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels by 2030, seen as essential to staving off the worst effects of climate change.

A handful of utilities continue to operate coal plants with no plans to shut them down, defying economic and political headwinds.

Market Forces launched a campaign Monday called “GE Get Out of Coal” and released an open letter signed by 65 activist groups from the 17 countries, calling on the company to cease supporting coal plants.

Many of GE’s projects are already delayed because of legal troubles, public opposition and difficulties obtaining financing — a reflection of the diminishing global market for coal power. In January, Bloomberg News reported that GE was looking to sell its steam power unit, which supplies coal plants, part of its larger power business, which had revenues that fell by 22% in 2018.

Publicly, the company emphasizes renewables: It has agreements to develop at least 1,800 megawatts of wind power in Vietnam, with some equipment manufactured at its factory in the coastal city of Hai Phong. Its coal projects are bigger but less well known.

“I was surprised to hear about Vung Ang 2 because in Vietnam we think of GE as a green company,” said Nguy Thi Khanh, founder of the Green Innovation and Development Center, one of Vietnam’s leading environmental groups. “I wondered why GE was involved in this.”

According to the Global Coal Plant Tracker, GE has agreed to supply equipment — including steam turbines and boilers — at 19 overseas coal projects that account for 15 gigawatts of electricity. If GE were a country, it would have the seventh largest slate of upcoming coal plants in the world, according to Market Forces.

GE has endorsed the Paris climate agreement and says renewable energy is its future. But its thermal power business — built on installing and operating coal and gas plants — has long been the core of the company, once the most valuable in the world.

In 2015 GE made an ill advised bet on the future of fossil fuels, paying $13 billion to acquire a French energy company, Alstom, and doubling its fleet of coal plant turbines. That investment collapsed as the market for renewables took off, erasing 74% of GE’s value in three years.

In the last-ditch global battle against climate change, China, Japan and South Korea have joined other industrialized nations in promising to reduce their use of fossil fuels.

The closure of coal plants in the U.S. and Europe has forced GE to look to emerging markets.

“What you’re seeing is essentially a fire sale,” said Melissa Brown, director of Asia energy finance studies at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “This is a liquidation strategy that, at this stage of the game, reeks of desperation. They are literally trying to sell anything they can, wherever they can.”

As a result, analysts say, GE has become entangled in controversial projects. In Kenya, a court last year halted a 1,000-megawatt power plant on Lamu island, adjacent to a UNESCO World Heritage Site, ruling that the Kenyan and Chinese developers had failed to conduct proper environmental assessments.

A Chinese-backed power plant at Tuzla in Bosnia-Herzegovina, due to use GE equipment, is moving ahead despite violations of European Union financing and pollution control standards, according to Bankwatch, which monitors investments by European public banks.

After a project in Poland was suspended last month because of difficulties obtaining financing, state-owned utilities opened talks with GE to convert the power station from coal to gas.

A separate GE project in southern Vietnam has been delayed after a Russian contractor, Power Machines, was hit with U.S. sanctions over Moscow’s military interventions in Ukraine and Crimea.

There is no construction date set for Vung Ang 2, which has been in the planning stages for more than a decade. Two banks and a Hong Kong-based power company have withdrawn from the project in recent months, but the Vietnamese government says it expects the plant to begin operating in early 2024.

The $2.2-billion project has raised controversy in part because of its location — across a bay from a steel mill where a 2016 chemical spill destroyed hundreds of acres of coral reefs and poisoned more than 100 tons of fish, their carcasses washing ashore across four provinces.

The spill — widely described as Vietnam’s worst environmental disaster — and emissions from the coal plant have devastated the fish trade upon which the villagers surrounding Vung Ang have relied for generations. A dangerous human trafficking operation thrives here as many young men seek jobs in Europe; of the 39 Vietnamese migrants found dead in a truck outside London last fall, several hailed from this area.

According to documents published by a Japanese government bank linked to the project, developers informed nearby residents in writing that they would minimize pollution and fairly compensate anyone whose land was needed to build the plant. In October, local officials held a meeting where they encouraged residents to sign papers agreeing to sell farmland, even though the price hasn’t been set.

In Ky Loi, a village of single-story concrete homes where red Vietnamese flags wave from bamboo poles, residents complained of chronic coughs and itchy skin. They all blamed the culprit they could see from their front doors: the red-and-white smokestack of the existing power plant.

No one had told them if they would be relocated for the second one.

“We don’t want to live next to this pollution, but we don’t know what’s going to happen,” said Le Ngoc Anh, a 65-year-old fisherman. “Poor people don’t get a choice.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.