- Share via

GARZE, China — American photographer Eleanor Moseman was documenting Tibetan life when the coronavirus crept into one of China’s most remote areas. She had made the journey to celebrate the Tibetan New Year with friends, but the virus outbreak gave her a remarkable glimpse into a culture of monks, nomads and life at the distant edges.

Moseman has been working for several years on a photography project of a Tibetan prefecture. She knows its people, their rhythms and superstitions. While Beijing and virus epicenter Wuhan were under surveillance and lockdown, the Tibetan prefecture in Sichuan province in the early days seemed oblivious to a mysterious illness that was making its way toward an autonomous land marked by mountain ranges and curled-roofed monasteries.

The following is what Moseman saw as she traveled in the prefecture for one month, watching China’s virus control measures play out in a Tibetan context. Her recollections were told to The Times’ Beijing correspondent and edited for clarity:

Jan. 17: I arrived in China a week before the New Year. At that time, few people were thinking about the virus.

When I took a high-speed train from Shanghai to Chengdu on my way to Garze, the station was as crowded as ever, filled with people heading home to see their families.

A friend from Chengdu texted me on the train, telling me to wear a mask. But almost nobody was wearing one. There was no sense of alarm.

Jan. 18-19: There are multiple Tibetan kingdoms in China. Garze is part of a kingdom called Kham Tibet, or east Tibet. It is still mostly Tibetan, though there is an influx of Chinese. The high school there is one of the major schools in the area. It’s a hub for nomads and herdsmen and villagers to come and buy supplies.

A lot of self-immolations — protesting Chinese controls and suppression of Tibetan culture — have happened in this area, so the city can get shut down at a moment’s notice. I’ve been stopped by police at checkpoints and told to leave right away.

It’s a precarious area and I never really know if I will get where I’m going or not.

But when I arrived this time, life seemed to be going on as usual. Nomads from the countryside were coming to shop, dressed in their colorful winter clothing. There are natural hot springs in the town where people gathered at night, sitting close together and dipping their feet in. I wasn’t so sure it was a good idea to share communal water like that.

Jan. 20-27: My friend Jacob, a Tibetan who teaches English, brought me to his village for Losar, the Tibetan New Year. They chopped up a yak’s head that we boiled and ate, wrapped in buns called momos. I stayed with his family for about a week.

At this point, news about the virus was beginning to spread on foreign media. I started getting calls from friends and family, but people in the Garze district didn’t seem concerned.

I was getting nervous about staying in Jacob’s home, especially as the kids in his family were sick with colds. I didn’t want to catch anything and get quarantined out of suspicion.

No one in the household was worried. But on Jan. 26 two coronavirus cases were confirmed in the Kham region. No one was panicking, but there was concern.

My friends in the region began saying politely, “Don’t come around.” As an outsider, I had suddenly become suspect.

As news of the virus spread, Jacob’s family discussed its source, which led to a larger talk on Tibetan beliefs on mortality. Jacob’s father linked the virus to a concept of “degeneration,” the shortening of Tibetan lives as predicted in Buddhist scriptures because of immoral and impure practices brought by the Chinese.

His examples were unclean food, bad air, pollution and now the coronavirus.

Jacob disagreed. He thought the the concept was unscientific.

I just kept trying to persuade them to make all the kids wash their hands.

Jan. 28-29: I managed to leave the village and head back to Garze by hitching rides on minivans that function like shared taxis. The first was filled with Tibetans, the second filled with Han Chinese migrant workers.

They were looking at maps on WeChat of reported virus cases, and pointing to the Tibet Autonomous Region.

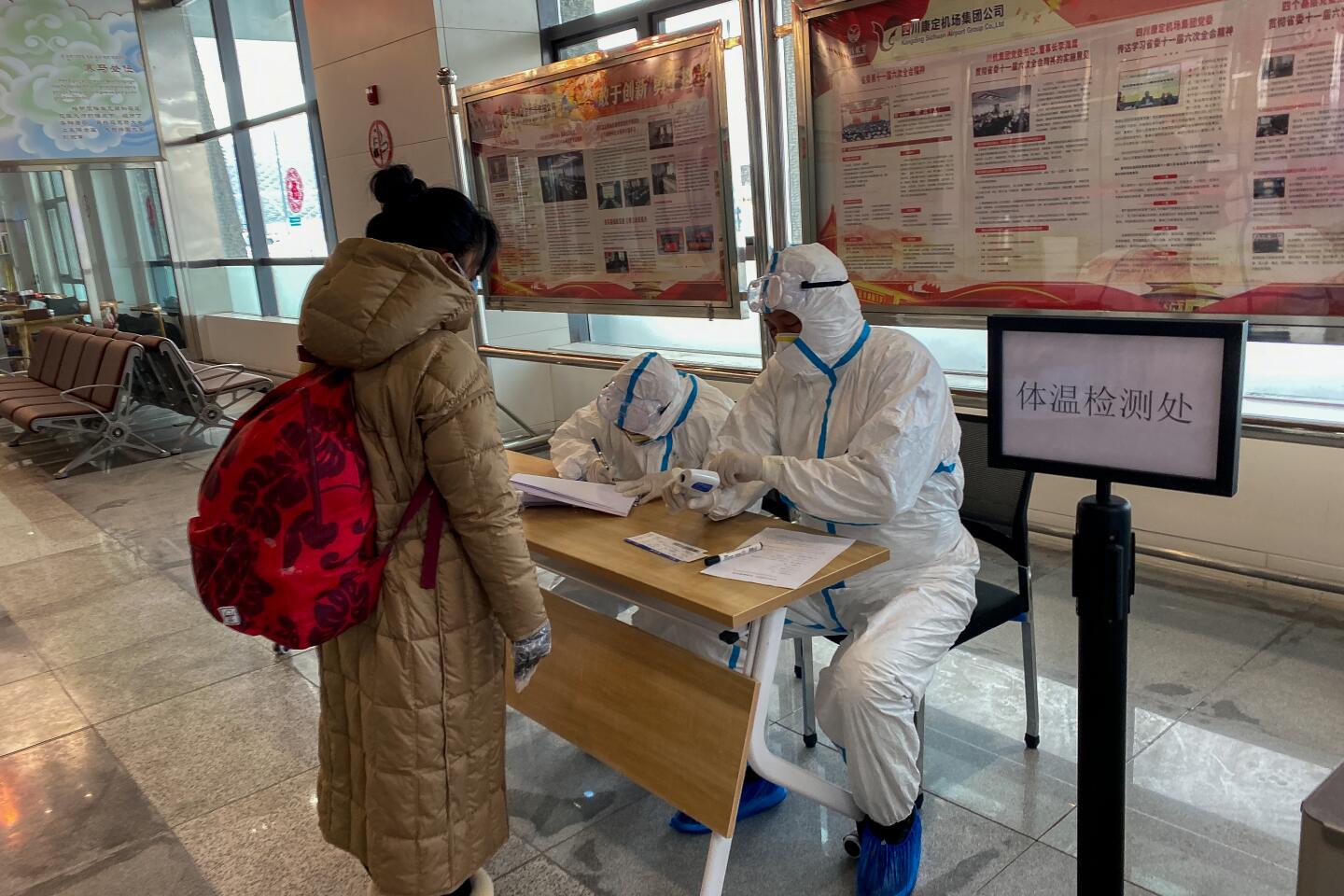

We drove through several checkpoints, where police and medical workers in white protective suits took our temperatures and examined our papers.

The third shared taxi I took was filled with Tibetans. I immediately felt like what I was: a foreigner. An older man pushed himself away, leaning toward the door as soon as he saw me, and wrapped a dirty scarf around his head, leaving only his eyes showing.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

I’d never been treated with suspicion like this in all the times I’ve been to this region. I laughed and told him not to worry, that I was healthy and visiting Tibetan friends.

A friend who is a monk sent me a photo of an ancient Tibetan text explaining how humans should not eat bats, which are believed to be the genesis of the coronavirus. There were a number of moments like this: modern-day disease and science mixing with an ancient religion that believes in reincarnation.

Jan. 30: I arrived in Garze. It was a ghost town. I’d never seen it like this. It was unnerving. The only hotel that would take me in was directly across from the police station.

I started seeing sanitation vans and hearing propaganda shouted on the loudspeakers. Posters were going up and police checked shops, telling owners to close. Guards blocked entrances to alleys, registering people’s names and IDs whenever anyone passed.

The city was slowly shutting down.

Feb. 8: A tour bus stopped at my hotel around midnight with police escorts. Six or seven people got off the bus. They were dressed and packed like nomads from the countryside. One woman walked as if she was unwell. A small child with them cried through the night.

I’d heard that police were putting foreigners and tourists in the same hotel as people they thought were carrying coronavirus in Yushu, another Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Qinghai province. So when this bus showed up, my alarm bells went off.

In the morning, those who had arrived late at night left. I opened the door and my hallway was being disinfected. A man came into my room and started spraying everything.

I asked the hotel manager what had happened. He said, “They’re just cleaning up because a lot of people stayed here last night.”

I asked him, “Are you afraid?” He said, “No. The girls that work here are a little afraid, but we shouldn’t be.”

Who knows what the police told them.

Feb. 14: My hotel finally told me I couldn’t stay anymore. The day I checked out, the hotel staff was shaking out a week’s worth of dirty linens in the lobby. They were wearing masks.

It was getting difficult to stay. It felt more menacing. There were groups of security officers at every village entrance and green government vehicles on the streets. Signs were posted in Tibetan and Chinese, explaining how to prevent and control the virus. Earlier warnings of the virus were written only in Chinese, which many Tibetans didn’t speak.

I tried to visit a temple one day and found that all had been closed. Locals were told not to pray at community prayer wheels. But I spotted one woman at the temple, turning the prayer wheel anyway.

Food costs started going up. I worried about Tibetan friends who struggle with poverty, especially women. I’ve accompanied them to hospitals in the past, where they have a hard time communicating with Chinese doctors.

One woman I’d hoped to visit is 70 years old and very protective of me. But there was no way of seeing her this time, with all the roads and villages shut down — even though she lived only 90 minutes away. She sent me voice messages on WeChat, crying and calling me her “child.”

I felt helpless.

Feb. 15: It was so strange to leave the region like this. Military tents were lining the road to Garze’s airport, guarding village entrances. It had taken hours the previous night, with a friend’s help, to find a car that was willing and able to drive an hour out of the city.

Garze felt even more like a police state than usual. I worried that the new forms of surveillance and control would be left in place even after the outbreak — and that people would accept them, because they’ve been told these measures are for their health, well-being and best interest.

Police questioned me one more time at the airport. I was pulled out of the medical check line for a high temperature. They used a small thermometer on my forehead, wrist and neck, and then stuck a thermometer under my armpit and told me to keep it there for eight minutes.

They let me on the plane.

Feb. 16: I flew to Chengdu, then to Shanghai, where I was shocked. Things were so different there. People were still living their lives, though there were temperature checks and masks. There was much less of a security presence.

Garze city has changed dramatically in recent years. When I first visited in 2011, it was all gravel roads, and now there’s a highway, hotels are popping up, a lot of new infrastructure and tourism. It’s on a major thoroughfare to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital.

Sometimes, I think this area is not ready for all these changes. The Chinese build and change at such a fast rate, it seemed like this area was going to stumble and fall to catch up.

The virus highlighted preexisting cracks in the social structure and medical system: difficulties in accessing healthcare, lack of education, and distrust exacerbated by cultural differences and inability to communicate.

After I left, Jacob’s village was locked down. His internet was knocked out as well.

That happens a lot there, especially in March, around the anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s exile. China wants to subsume Tibet, make its culture and beliefs bend to the Chinese way, even here — thousands of miles from Beijing.

I got a text from Jacob later. He said, “I have faith in our government that they’re doing the best they can do. Our village leaders said cases will decrease soon.”

I don’t know why he sent those messages. It’s really hard to say.

Moseman is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.