North Korea’s official coronavirus count: Zero. Why that claim is hard to believe

- Share via

SEOUL — If the country is to be believed, North Korea is one of maybe a dozen nations not yet invaded by a deadly virus that has spread across the globe from remote islands in the South Pacific to outposts nestled high in the Pyrenees or the Greater Himalayas.

North Korea’s assertion would mean that despite sharing a nearly 900-mile border with China, one tens of thousands have crossed to escape or navigated as part of a robust smuggling trade, the isolated nation has managed to block a mercurial virus that has upended richer and more powerful countries.

The U.S., its longtime existential foe, has more than a quarter of a million confirmed cases of the coronavirus. China, its erstwhile backer and most important trading partner, has more than 80,000.

North Korea’s official coronavirus count is zero.

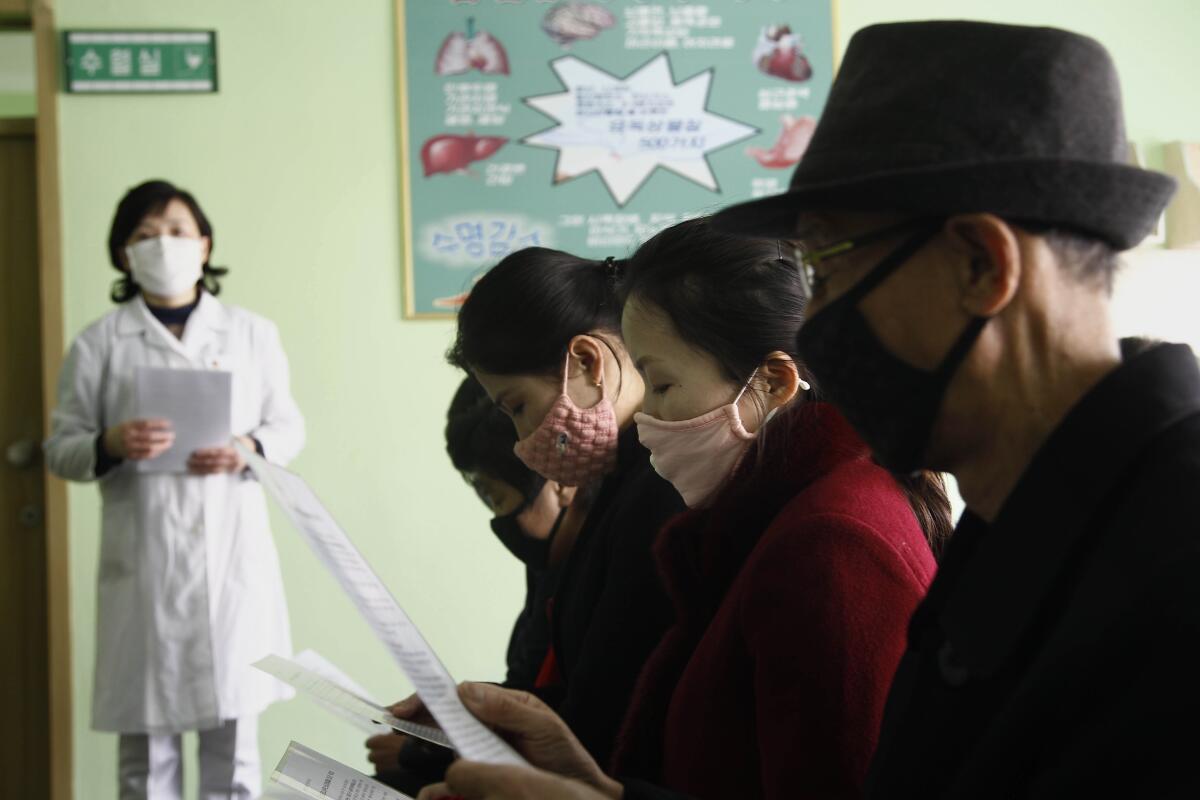

The tightly controlled country has boasted to its people that international organizations and public health experts were marveling at its success in keeping the virus at bay. As recently as this week, a state health official rebuffed suspicions that the country was being less than forthcoming about its coronavirus situation, telling foreign reporters in Pyongyang that not a single person had come down with COVID-19 thus far.

The lack of free media and scant independent monitoring make it nearly impossible to vet the official account. Yet many outside observers and officials have questioned the country’s claim, alleging the regime of Kim Jong Un may be suppressing information or willfully blind to potential local outbreaks because it lacks the capacity to conduct widespread diagnostic testing.

With a poorly equipped medical system ravaged by sanctions in recent years, the country has struggled with a population susceptible to infection, widespread malnutrition and inadequate sanitation. An outbreak of the coronavirus may be an impending disaster, former North Korean health professionals and outside experts say.

“You can’t trust North Korean statistics,” said Choi Jung-hun, who worked for a decade as a physician in North Korea before escaping in 2011. “The epidemic really plainly shows the nature of the North Korean regime. ... The regime’s face saving is more important than citizens’ health or life.”

In fact, North Korea was one of the first countries in the world to take swift action as the coronavirus began spreading in China. It closed its borders to foreign tourists in January, around the same time China imposed travel restrictions in Wuhan. It imposed strict, lengthy quarantines on foreign diplomats and canceled virtually all international flights. More than 10,000 of its citizens were placed under isolation or travel restrictions as measures against the virus.

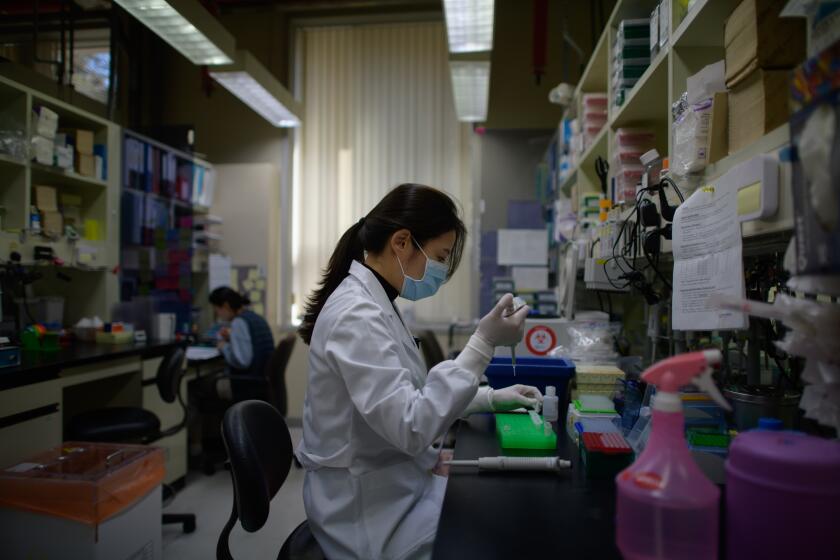

South Korea has far outpaced other countries including the U.S. in coronavirus testing, a move that could mean early detection and lives saved.

Nagi Shafik, a public health advisor and a former project manager for the World Health Organization in North Korea, said the early drastic steps indicated how cognizant the government was of the threat that an epidemic could pose to its stability.

“They don’t have medicine,” he said. “They don’t have reagents to diagnose cases. They don’t have protective equipment. If I were them, I would do the same thing, this is the only thing I have. To close borders with China, this is the lifeline for them. It shows you how desperate they were.”

But as much as North Korea’s authoritarian system is able to impose severe restrictions on its citizens’ movements, the virus is likely to make it into the country at some point if it hasn’t already, he said.

“Sooner or later something will spill over,” said Shafik, who last visited the country in 2019 to consult on a humanitarian mission. “Whatever you try, everywhere in the world, some people go through the borders without being noticed.”

Choi, the North Korean doctor who now works as a research professor at South Korea’s Korea University, said even though North Korea was plagued with infectious diseases, its capacity to conduct laboratory tests to diagnose them was minimal during his years of working there. When an illness began spreading in the country’s northern region around 2006, officials mistook it for scarlet fever for more than two months before finding out that it was, in fact, measles, he recalled.

In the absence of testing, patients would die from symptoms matching an infectious disease without doctors ever getting confirmation of what the person was sick with, according to Choi. Many patients simply turned to antibiotics across the board, creating drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis or typhus, he said.

“It’s not like there’s proper treatment even if people are diagnosed,” Choi said. “The basic infrastructure like electricity and water isn’t a guarantee even at medical clinics. Medical supplies and equipment are antiquated.”

In mid-February, North Korea quietly reached out to international organizations and nonprofits requesting assistance such as diagnostic test kits, protective gear and equipment, including ventilators and oxygenators. Russia in late February sent 1,500 coronavirus test kits to North Korea at its request, according to the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Groups including Médecins Sans Frontières, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent and the World Health Organization obtained humanitarian exemptions from the U.N. committee overseeing sanctions to send in coronavirus-related relief supplies.

Since some of the outside supplies have arrived, the country has been conducting about 60 tests a day for the coronavirus, having completed about 1,000 as of this week, according to a person familiar with humanitarian efforts in North Korea who asked not to be named so as not to jeopardize their work in the country.

That’s a far cry from the widespread testing that’s being done in places like South Korea — which has tested more than 420,000 as of this week — to get a full picture on how the virus is spreading.

Even more dire than the virus’ potential impact might be the economic repercussions of sealing the border. Many North Koreans heavily rely on a network of unofficial markets, much of which is supplied by trade from China. For months before the coronavirus outbreak, many working on humanitarian assistance to North Korea had warned of food shortages in the country exacerbated by drought and international sanctions imposed in response to its weapons tests.

“This was a massive decision, with huge implications not just for the people but for the state economy,” said Kee B. Park, a consultant for the WHO and lecturer at Harvard Medical School who frequently travels to North Korea. “You might think it’s overreacting in a way, but they really understand the idea of breaking the transmission chain.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.