As Trump heads to Tulsa, foreboding grows among Black residents

- Share via

TULSA, Okla. — Trump supporters started lining up a week before the rally, camping on downtown sidewalks overnight despite 90-degree heat.

Many in the mostly white crowd were not worried about catching COVID-19. The atmosphere in line was festive. Some drivers dropped off bottled water and beeped encouragement as they passed Trump flags and a red, white and blue sign with the word “Freedom.”

But as night fell Wednesday, some drivers also shouted obscenities.

On the eve of Juneteenth, Tulsa appeared to channel the nation’s restiveness: coronavirus fears, unemployment worries, racial divisions following the killing of George Floyd and political rancor stirred by a president who thrives on stoking America’s anxieties and differences.

A black-owned Oklahoma newspaper would not let the state forget the day white mobs murdered hundreds of African Americans in Tulsa.

Near the site of Trump’s Saturday rally, in the city’s historically Black Greenwood District, foreboding was spreading about Trump. The Rev. Robert Turner, at Vernon AME Church, called it “a very high-octane time.” The neighborhood’s annual weekend-long Juneteenth festival was set to start Friday afternoon, a celebration of the day enslaved Black people in Texas received word of emancipation. Trump delayed his visit a day, but his impending arrival and comments still stirred fears.

“I made Juneteenth very famous,” Trump said in an interview with the Wall Street Journal on Thursday that provoked an immediate backlash. “It’s actually an important event, an important time. But nobody had ever heard of it.”

Oklahoma’s governor invited the president to visit Greenwood, known as “Black Wall Street,” before backpedaling this week. It still wasn’t clear Thursday whether Trump planned to tour the area, including a park dedicated to racial reconciliation. Black residents rebuilt Greenwood after white mobs destroyed it — including Vernon AME — during a massacre in 1921 that left as many as 300 Black people dead, buried in a mass grave that is still being investigated.

“I don’t want him in my city. I sure as hell don’t want him in Greenwood. It’s a slap in the face,” City Council Vice-Chair Vanessa Hall-Harper said. “We don’t have a very good track record when communities collide. They simply did not value Black life. And unfortunately, I do not think much has changed.”

Since Oklahoma reopened for business in April, Tulsa and the surrounding county have seen COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations increase, with Black and brown people at heightened risk. There will be temperature checks, and masks will be handed out at the rally. But Trump will not require attendees at the 19,000-seat arena and nearby 40,000-seat convention center to wear the face coverings. Those waiting outside this week had traveled from as far away as California, Oregon and New York. None wore masks. Some said they would if they made it inside.

Turner, the pastor, worried that white supremacists and neo-Confederates would be drawn by Trump.

“He is their president. They are going to come travel to see him, and Oklahoma is a hotbed,” he said. “I really hate the president chose this time to come to Tulsa. We don’t need candidate Trump — we need President Trump.”

Turner said he was encouraged by how many “white allies” had joined protests last month, and that if they appeared again alongside Trump counter-protesters this week, police would be less likely to target the crowds with tear gas and other “less lethal” weapons.

“I hope that they protect and serve the citizens of Tulsa and the folks that are exercising their 1st Amendment rights,” Greg Robinson, a Black community organizer running for mayor, said of Tulsa police.

Greenwood businesses scrambled to add private security this week ahead of Juneteenth, when thousands are expected to gather and the Rev. Al Sharpton is scheduled to speak. Ricco Wright, owner of the Black Wall Street Gallery, said he’d already received arson threats from white supremacists. Those planning Trump protests worried whether police would protect them. The Tulsa World published an editorial with the headline, “This Is the Wrong Time and Tulsa Is the Wrong Place for the Trump Rally.”

Tulsa saw protests last month marking the anniversary of the massacre and the killing of George Floyd. There were reports of looting and police using tear gas, but violence was minimal. Now some gas stations surrounding downtown are planning to close. Other businesses were boarding up. Police from outside the city were being brought in to assist, as well as 250 Oklahoma National Guard troops.

“Tulsa is not prepared,” said Hall-Harper, whose husband is president of the city’s Black Police Officers Coalition. “This is just the perfect storm for something very bad to happen in this community. I wish that leadership in this state and in this city would have done something to stop it from coming here at this time.”

State Rep. Regina Goodwin, who represents the Greenwood District, believes the president’s goal is to stoke fear and racial strife in a Republican stronghold despite the pandemic.

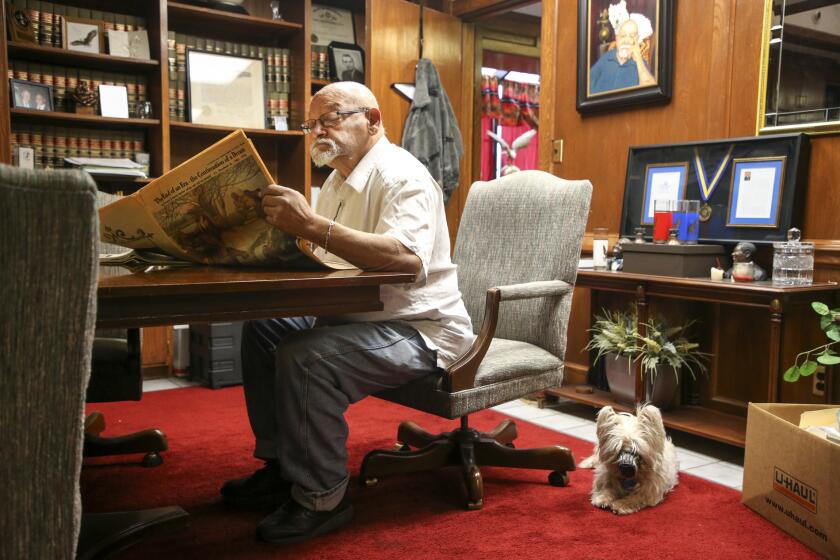

“He wants a charged atmosphere, he wants chaos, he wants division,” said Goodwin, whose family runs a Black-owned newspaper here. “The people who are going to attend are not safe, and the people who feel moved to protest this visit, which are many, will be at risk.”

Waiting in line late Wednesday in Trump hats, Tulsans Bill and Traci Rhodes said they “wanted to be part of history” but worried about counter-protesters, looting and whether they would be able to reach their car safely after the rally.

“I’m concerned about not being able to get away,” said Traci Rhodes, 46, who is diabetic and has difficulty walking.

The couple, who are white, said they had never been to Greenwood. They said they had learned about the 1921 “race riot” only recently on the news and said it should have been taught in public school when they were growing up. But they did not believe racism was systemic in the city or its Police Department, which they trusted to protect them.

Both hoped violence would not erupt over the weekend.

“You don’t want to see anything bad happen to anybody,” said Bill Rhodes, 50, who works on industrial tires. “We all bleed the same.”

Tykebrean “Ty” Cheshire, 21, is organizing a “Rally Against Hate” on Saturday at a park a mile and a half south of where Trump is holding his rally. She hopes to keep it peaceful, but she said the physical damage done in recent weeks had accomplished a purpose.

“Looting and rioting was the beginning,” she said. “It did its purpose: It got us all riled up. But now let’s use that anger to make change and get people to listen to us.”

Tulsa is a city of nearly 400,000, in the heart of a metro area more than twice that size, with a Black population of 15%. It’s an energy and arts hub, is home to two universities and is less conservative than the rest of the state. Mayor G.T. Bynum, a Republican whose grandfather, great-grandfather and cousin all served as mayor, said this week that he was glad Trump chose Tulsa for the rally even though he wasn’t sure it was safe.

“I don’t care if you’re a Republican, a Democrat or an Independent, that’s a tremendous honor for our city to be highlighted in that way and I’m very grateful,” Bynum said during a Wednesday briefing with the police chief.

The mayor said he planned to welcome Trump at the airport Saturday, but instead of attending the rally, he would “be out with our police officers who have been working their tails off.”

“The eyes of the world are on Tulsa, Okla., during this event, and we are ready for it,” said Police Chief Wendell Franklin, the first Black officer to lead the agency. “We’re going to protect all the people who come to our city and do that in a professional way.”

City leaders have resisted independent oversight of police even after several controversial officer-involved shootings of unarmed Black men in recent years.

During a traffic stop four years ago, a white police officer shot and killed Terence Crutcher, 40, whose twin sister, Tiffany, has become a vocal advocate for police oversight.

Tiffany Crutcher noted that earlier this month a viral video showed Tulsa police handcuffing two Black teenagers for jaywalking in a neighborhood without sidewalks. Last week, a police commander told a local radio station: “We’re shooting African Americans about 24% less than we probably ought to be based on the crimes being committed.”

“These comments and these actions are what we’re up against here in Tulsa,” Crutcher said.

She worried Trump’s rally could incite violence, echoing the clash between white supremacists and protesters three years ago in Charlottesville, Va., where a female protester was killed. Afterward, Trump faulted “both sides.”

“My heart breaks thinking about what could happen here,” Crutcher said.

In Greenwood, Wright was planning a Trump protest outside his gallery Saturday and stocking up on T-shirts featuring Toni Morrison, Angela Davis and other Black intellectuals ahead of Juneteenth (he sold out during last month’s protests).

Wright, 38, was also campaigning like Robinson, hoping to become the city’s first Black mayor. As a fourth-generation Tulsan, he’s seen power passed down to Bynum and other white leaders, who built the downtown’s Art Deco skyscrapers even as they limited Greenwood’s rebuilding to three stories.

There’s a reason Greenwood observes the anniversary of the massacre, Wright said, rather than its founding: Their narrative is tragedy, not triumph; reconciliation is an illusion.

“It’s a racist city,” he said. “Historically and present time.”

Hennessy-Fiske reported from Tulsa and Lee reported from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.