In graying Italy, the old defy biases laid bare by the pandemic

- Share via

ROME — From his newsstand at the bottom of two hilly streets in Rome, Armando Alviti has been dispensing newspapers, magazines and good cheer to locals from before dawn till after dusk nearly every day for more than half a century.

“Ciao, Armando,” his customers greet him as part of their daily routine. “Ciao, amore [love],” he calls back. Alviti chuckled as he recalled how, when he was a young boy, newspaper deliverers would drop off the day’s stacks at his parents’ newsstand, sit him in the emptied baskets of their motorbikes and take him for a spin.

Since he turned 18, Alviti has operated the newsstand seven days a week, with a wool tweed cap to protect him from the Italian capital’s winter dampness and a tabletop fan to cool him during its torrid summers. A mighty battle therefore ensued when the coronavirus reached Italy and his two grown sons insisted that Alviti, who is 71 and diabetic, stay home while they took turns juggling their own jobs to keep the newsstand open.

“They were afraid I would die. I know they love me crazy,” Alviti said.

Throughout the pandemic, health authorities around the world have stressed the need to protect the people most at risk of complications from COVID-19, a group that infection and mortality data quickly revealed included older adults. With 23% of its population age 65 or older, Italy has the world’s second-oldest population, after Japan, with 28%.

Italy could soon reclaim a record — the most COVID-19 deaths in Europe — and is still trying to figure out how to protect its older people.

The average age of Italy’s COVID-19 dead has hovered around 80, many of them people with previous medical conditions like diabetes or heart disease. Wanting to avoid lockdowns of the general population that were costly to the economy, some politicians advocated limiting how much time elders spent outside of their homes.

Among them was the governor of Italy’s northwestern coastal region of Liguria, where 28.5% of the population is age 65 or older. Gov. Giovanni Toti, who is 52, argued for such an age-specific strategy when a second surge of infections struck Italy in the fall.

Older people are “for the most part in retirement, not indispensable to the productive effort” of Italy’s economy, Toti said.

To the news vendor in Rome, those were fighting words. Alviti said Toti’s remarks “disgusted me. They made me very angry.”

“Older persons are the life of this country. They’re the memory of this country,” he said. Self-employed older adults like him especially “can’t be kept under a bell jar,” he said.

The pandemic’s heavy toll on older people, particularly those in nursing homes, might have served to reinforce ageism, or prejudice against the segment of population generally referred to as “elderly.”

The label “old” means “40, 50 years of life being lumped in one category,” said Nancy Morrow-Howell, a professor of social work at Washington University in St. Louis who specializes in gerontology. She noted that these days, people in their 60s often are caring for parents in their 90s.

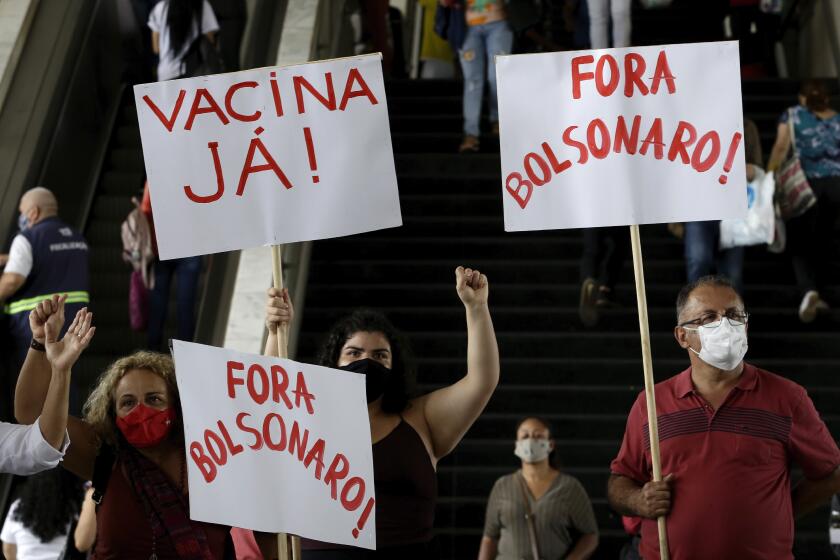

Brazil appears to be at least weeks away from any formal immunization campaign against COVID-19, putting it behind other South American countries.

“Ageism is so accepted ... it’s not questioned,” Morrow-Howell said in a telephone interview. One form it takes is “compassionate ageism,” Morrow-Howell said, the idea that “we need to protect older adults. We need to treat them as children.”

Alviti’s family won the first round, keeping him away from work until May. His sons implored him to stay home again when the coronavirus rebounded in the fall.

He struck a compromise. One of his sons opens the newsstand at 6 a.m. and Alviti takes over two hours later, limiting his exposure to the public during the morning rush.

Fausto Alviti said he’s afraid for his father, “but I also realize for him to stay home, it would have been worse, psychologically. He needs to be with people.”

In the open-air food market in the Trullo neighborhood of Rome, produce vendor Domenico Zoccoli, 80, also scoffs at the belief that people past retirement age “don’t produce [and] must be protected.”

Before dawn broke on a recent rainy day, Zoccoli had transformed his stall into a cheerful array of colors: boxes of red and green cabbages, radicchio, purple carrots, leafy beet tops, and cauliflower in shades of white, violet and orange, all harvested from his farm some 18.6 miles away.

“Old people must do what they feel. If they can’t walk, then they don’t walk. If I feel like running, I run,” Zoccoli said. After packing up his stall at 1:30 p.m., he said he would work several hours more in his field, skipping lunch.

Marco Trabucchi, a psychiatrist based in the northern Italian city of Brescia who specializes in the behavior of older adults, thinks the pandemic has gotten people to reconsider their attitudes for the better.

“Little attention was given to the individuality of the old. They were like an indistinct category, all equal, with all the same problems, all suffering,” Trabucchi said.

In Italy, with childcare centers chronically scarce, legions of older adults, some decades beyond retirement, effectively double as essential workers by caring for their grandchildren.

A veteran critical care nurse in northern Greece didn’t feel good about the treatment options available when his wife, both her parents and her brother got COVID-19 in alarming succession.

According to Eurostat, the European Union’s statistics bureau, 35% of Italians older than 65 look after grandchildren several times a week.

Felice Santini, 79, and his wife, Rita Cintio, 76, are such a couple. They take care of the two youngest of their four grandchildren multiple times a week.

“If we didn’t care for them, their parents couldn’t work,” Santini said. “We’re helping them [a son and daughter-in-law] stay in the productive work force.”

Santini still works himself, half a day as a mechanic at an auto repair shop. When he comes home, his hands keep busy in the kitchen: stuffing homemade cannelloni with sausage, making meat sauce and baking orange-flavored Bundt cakes for his grandkids.

Cintio finds it painful not being able to hug and kiss her grandchildren. But she embraced 9-year-old Gaia Santini when the girl ran joyfully toward her after her grandmother navigated Rome’s narrow streets to pick her up at school. Cintio will take Gaia home for a break, before next accompanying her to an ice-skating lesson.

Worried about COVID-19’s second surge, the couple’s son, Cristiano Santini, said he tried to limit the frequency with which his parents watch the children, but to little avail.

“They’re afraid [of infection], but they are more afraid of not living much longer” due to their ages and missing precious time with their grandchildren, he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.