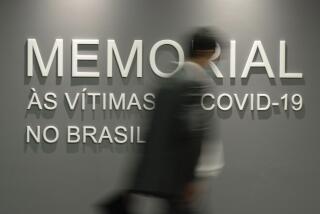

Brazil death toll tops 250,000 as virus continues to run rampant

- Share via

RIO DE JANEIRO — Brazil’s COVID-19 death toll, which surpassed 250,000 on Thursday, is the world’s second-highest for the same reason its second wave has yet to fade: Prevention was never made a priority, experts say.

Since the pandemic’s start, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has scoffed at the “little flu” and lambasted local leaders for imposing restrictions on activity; he has said the economy must keep humming along to prevent worse hardship.

Even when he approved pandemic welfare payments for the poor, they weren’t announced as a means to keep people home. And Brazilians remain out and about as vaccination has started up — but rollout has proved far slower than anticipated.

“Brazil simply didn’t have a response plan. We’ve been through this for the last year and still we don’t have a clear plan, a national plan,” Miguel Lago, executive director of Brazil’s Institute for Health Policy Studies, which advises public health officials, told the Associated Press. “There’s no plan at all. And the same applies to vaccination.”

Whereas other countries’ daily cases and deaths have fallen, Latin America’s largest nation is parked on an elevated plateau — a grim repeat of mid-2020. In each of the last five weeks, Brazil has averaged more than 1,000 daily deaths. Official data showed a confirmed total death toll of 251,498 on Thursday.

At least 12 Brazilian states are in the midst of a second wave even worse than the one faced in 2020, said Domingos Alves, an epidemiologist who has been tracking COVID-19 data.

“This scenario is going to get worse,” Alves told the AP, adding that the virus was spreading faster among the population. In Amazonas state, where the capital, Manaus, saw hospitals run out of oxygen last month, there have been more than 5,000 deaths in the first two months of the year, about as many as in all of 2020.

Traveling to remote communities in Brazil’s Amazon is only the first challenge for health workers vaccinating Indigenous and riverine people against COVID-19.

“It is the most difficult moment that we have had since the confirmation of the first case,” Carlos Lula, chair of the National Council of Health Secretaries, was quoted as saying Thursday by O Globo newspaper. “We have never had so many states with so much difficulty at the same time.”

Alves and other public health experts said the spread is exacerbated by authorities’ reluctance to follow recommendations from international health organizations to implement stricter restrictions.

It is up to governors and mayors to impose lockdowns or other restrictions to contain the virus. The states of Sao Paulo and Bahia recently introduced nighttime curfews, but experts say the moves are too late and insufficient.

“They are not containment measures; they are palliative measures, always taken after the fact,” said Alves, who is also an adjunct professor of social medicine at the University of Sao Paulo. “‘Lockdown’ has become a curse word in Brazil.”

Miguel Nicolelis, a prominent Brazilian neuroscientist, warned in January that the nation had to enter lockdown or “we won’t be able to bury our dead in 2021.” He had been advising northeastern states on how to combat COVID-19 but recently left his position, dissatisfied with their refusal to go into lockdown, the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper reported.

“Right now, Brazil is the largest open-air laboratory, where it is possible to observe the natural dynamics of the coronavirus without any effective containment measure,” he wrote on Twitter on Tuesday. “Everyone will witness the epic devastation.”

There are some exceptions, but they remain marginal and have failed to inspire a broader movement.

Sao Luis, capital of the northeastern state of Maranhao , was the first Brazilian city to go into full lockdown in May. It was successful, notwithstanding Bolsonaro’s efforts to undermine the restrictions and sow doubt about their efficacy, according to the state’s governor, Flávio Dino.

“It has been very difficult to manage distance and prevention measures,” Dino said, adding that the first obstacle was an economic and social one, especially after the federal government’s emergency pandemic aid program ended last year.

Lago noted that Bolsonaro rarely even comments on the pandemic anymore and has in effect moved on to other priorities, including securing support in Congress for loosening gun control laws and passing economic reforms. His administration is seeking to reinstate some COVID-19 welfare payments, but for a smaller group of needy Brazilians.

The only preventive measure Bolsonaro consistently supported was the use of treatments like hydroxychloroquine, which showed no benefit in rigorous studies.

Bolsonaro’s administration has also adopted a hands-off approach regarding the vaccination campaign. It relied mostly on a deal to purchase a single vaccine, made by AstraZeneca, which has been slow in coming. The national immunization effort to date has relied mostly on Chinese-made CoronaVac shots secured by Sao Paulo state, though the federal government is now trying to buy others.

Brazil’s decades of experience with successful vaccination programs and its large nationwide public health care network led many experts to believe that immunization — even if it were to start with a delay — would be a relatively speedy affair. In previous campaigns, the nation of 210 million was able to vaccinate as many as 10 million people in a single day, health experts noted.

Five weeks after the first shot, Brazil has vaccinated only 3.6% of its population. That is more than double the rate in Argentina and Mexico, but less than one-fourth that of Chile, according to Our World in Data, an online research site that compares official government statistics.

“There is no way to be fast with a shortage of vaccines; that is the crucial point,” said Carla Domingues, who for eight years coordinated Brazil’s national vaccination program before leaving her position in 2019. “Until there is greater supply, the speed will be slower, as you have to keep selecting who can be vaccinated.”

Meantime, the virus continues to run rampant across Brazil.

In Araraquara city in Sao Paulo state, there have been more deaths so far this year than all of last year and intensive care unit occupancy surpassed full capacity, with people on waiting lists to enter ICUs and get treatment. Local authorities responded Sunday by announcing a full lockdown — making Araraquara only the second city to impose such a restriction.

“We never imagined we would reach this point,” said Fabiana Araújo, a nurse and a coordinator of the city’s committee to fight COVID-19. “It was the only option.”

Associated Press writers David Biller in Rio de Janeiro and Mauricio Savarese in Sao Paulo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.