How Alaska achieved one of the highest COVID-19 vaccination rates in the U.S.

- Share via

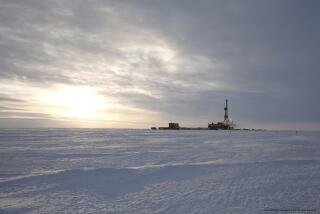

Bigger than California, Texas and Montana combined, Alaska is a forbidding expanse of mountains, tundra and wilderness dotted with villages so remote that many can be reached only by boat or small plane.

Few places would seem to pose as many challenges for a vaccination campaign.

Yet more than 28% of Alaskans have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine — better than most states and well above the national average of 22%.

Last week, Alaska became the first state to offer vaccinations to anybody at least 16 years old who wants them.

Mississippi has since followed suit, and Utah announced it will do the same starting next month, making the calculation that enforcing a hierarchy of eligibility was slowing down the effort to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible.

As the rest of the country grapples with the same issue, the success of Alaska offers a lesson in the benefits of avoiding the top-down bureaucracy that has hampered vaccinations elsewhere.

From the early days of Alaska’s campaign, local leaders around the state enjoyed some latitude in how to administer the doses they received.

The decision to officially scrap eligibility restrictions — which ran two dozen pages — came after state officials realized that many residents were confused about whether they qualified and that too many appointments were going unclaimed.

“It was astonishing to our team how much time and effort was being sucked up early on by constantly trying to make sure the right people got the vaccine, and nobody else,” said Tessa Walker Linderman, who co-leads the state’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force.

“Once we decided to open up the gates, we were able to step back, breathe and think more strategically about how to fill in gaps,” she said.

Gov. Mike Dunleavy says Alaska will become the first state to drop eligibility requirements and allow anyone 16 and up to get a COVID-19 vaccination.

Ethicists said in interviews that in the early days of the national vaccine rollout, it made sense to prioritize healthcare workers, nursing home residents and other vulnerable groups. But they worried that a continued focus on fairness — and the bureaucracy that entailed — was slowing the national campaign.

“In retrospect, it’s pretty clear that most states have been using too many criteria, making the allocation scheme seem either arbitrary, overly complicated or both,” said George Annas, a bioethicist at Boston University.

Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University, lauded the concept of local control, calling the top-down bureaucratic approach “one of the great ridiculous tragedies of this rollout.”

“We are way too far into the swamp of dictating how to do this fairly, and it’s getting in the way of distribution,” he said.

To be sure, Alaska has some key advantages over many other states when it comes to vaccination.

Members of the state’s 229 sovereign tribes were able to bypass the state’s eligibility tiers and receive vaccinations provided through the federal Indian Health Service.

Similarly, the state has a large population of military veterans, who are eligible for vaccination through the Defense and Veterans Affairs departments.

But even Alaska’s standard vaccine allocations appear to be going into arms faster than those of other states.

Dr. Anne Zink, the state’s chief medical officer, attributed its success to decades of experience dealing with the logistical challenges posed by the state’s harsh geography — to the point that even the process of getting Amazon packages to doorsteps has served as practice for vaccine delivery.

“Every Alaskan community looks different, and when we brought their representatives to the table, it was clear they each needed a different approach,” she said.

The public health system is well versed in getting childhood vaccines and flu shots to far-flung corners of the state.

Unlike most other state governments, Alaska has long needed to look beyond commercial pharmacies and partner with tribal health systems and community clinics that serve the most vulnerable groups.

There are few intermediaries in the state health system — Alaska does not have county health departments, for example — so state officials can provide resources directly to trusted local leaders, who then decide how best to address their population’s scenario.

In Indigenous villages in the Aleutian island chain, which stretches over 1,000 miles west from the Alaska Peninsula to Russia, health workers go door to door by dogsled to those without running water.

Project Togo, the current effort to get COVID-19 vaccines to 50 rural villages in the southwestern region of the state, was named after a sled dog who helped transport medicines during a diphtheria outbreak almost a century ago.

In an unusual arrangement with the federal government, the state receives its vaccine shipments monthly rather than weekly — a deal that Zink said state officials requested to allow for more systematic planning of how to distribute doses to match demand.

In the town of Petersburg, an island community off the coast of British Columbia, about half of the 3,200 residents have received at least one dose.

Jennifer Bryner, the chief nursing officer of Petersburg Medical Center, said she and her fellow administrators were given permission from the beginning to use the vaccines however they saw fit. That often meant that when elderly residents came for a vaccination, the people who brought them also got shots.

Her team conducts online polling through the website SurveyMonkey to gauge community interest and determine how many doses to request from the state.

If any doses are left at the end of a vaccination session, the medical center advertises them on Facebook. Bryner said not a single dose has gone to waste.

Linderman, of the COVID-19 task force, said that since eligibility requirements were lifted last week, Alaska has kept up with demand. Online dashboards where residents make appoints show about 2,000 slots still vacant in March.

“The concern was that providers would be hounded, that people would be knocking down their doors,” she said. “We haven’t seen that — just a consistent, steady flow of interest.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.