Migrant family’s case renews concerns about illegal deportations in Greece

- Share via

VATHY, Greece — Around dawn one recent spring day, an inflatable dinghy carrying nearly three dozen people reached the Greek island of Samos from the nearby Turkish coast. Within 24 hours, refugee rights groups say, the same group was seen drifting in a life raft back to Turkey.

But of the 32 people determined to have initially made it to Samos, only 28 were in the raft the Turkish coast guard reported retrieving at sea.

Four days later, the missing four — a Palestinian woman and her three children — appeared in Samos’ main town of Vathy, apparently having eluded Greek authorities. She applied for asylum and last week was informed their application had been accepted.

“I consider that the arrival of this woman, if we’re not speaking of a miracle, of a virgin birth, of her falling from the sky, we’re speaking of clear proof of a pushback,” said Dimitris Choulis, the lawyer who helped 31-year-old Huda Zaga apply for asylum, along with her 12-year-old daughter and sons, ages 11 and 5.

Juneteenth 2021: Movies, books, events, and podcasts to try

Accusations from rights groups and migrants that Greece has been carrying out pushbacks — the illegal summary deportation of migrants without allowing them to apply for asylum — are nothing new, on land or at sea. But it is rare for such cases to involve anyone managing to stay behind.

Greece vehemently denies the claims, but says it has an obligation to protect its borders, which are also the European Union’s external borders. It points to March 2020, when Turkey opened its borders into the EU and actively encouraged migrants to cross into Greece.

Zaga says she arrived on Samos on April 21 in a dinghy crammed with people. After making landfall, the group scrambled up a wooded hill, splitting up to avoid detection by authorities.

“We were terrified of being caught and being sent back to Turkey, especially after we crossed into the territorial waters of Greece,” Zaga told the Associated Press.

Before long, social media posts appeared. A local journalist posted about the migrants’ arrival. Other residents said they had seen them, or given them food or water.

But as the day progressed, the story changed. The journalist contacted authorities, and posted she was told the migrants were not new arrivals but residents of a refugee camp on the outskirts of Vathy making a day trip — a roughly 31-mile hike over mountains.

Several residents told the AP they were told by authorities and others not to speak of what they had seen. They spoke on condition of anonymity, saying they didn’t want problems.

The next day, a piece of the dinghy the migrants arrived in still lay on the beach of Marathokampos Bay. The rights group Aegean Boat Report, which monitors arrivals on Greek islands, posted photos of the new arrivals. Some showed Zaga and her children with others on a wooded hillside, the Marathokampos coastline in the background.

Asked about the case, Greece’s Shipping Ministry, under whose jurisdiction the coast guard falls, said it had no record of an April 21 arrival on Samos. Authorities did not provide any explanation for the appearance of the woman and her children.

Zaga said she was aware of the pushback risk, having experienced it before. She tried to enter Greece three times earlier from the land border but was caught twice inside Turkey and once after entering Greece. This time, she was determined to succeed.

“We managed the impossible, to make sure that what happened to them won’t happen to us,” she said of those returned to Turkey.

Zaga said she broke away from the others, staying behind with her children, and got in touch with people who had helped arrange her journey to Samos. She would not provide specifics about how she managed to evade detection, or who helped her contact the lawyer. But on April 26, she arrived at Choulis’ office asking for assistance.

Choulis said he immediately realized they were the people missing from the reported Marathokampos landing. He informed Greek judicial authorities, police and the coast guard that he was accompanying the family to the refugee camp for registration.

As he waited outside during Zaga’s registration interview, he was told repeatedly to leave, Choulis said.

“There was a strange climate of suspicion,” he said, and an intense fear that Zaga and her children might still be sent back to Turkey. But at this point, representatives of the U.N. refugee agency had been informed and were present.

Mireille Girard, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees representative in Greece, said the organization received a telephone message on April 21 about migrants arriving on Samos and sought confirmation from authorities, but got no response. A few days later, the agency was informed a family believed to have been with the group had remained on Samos and was applying for asylum.

“These elements are concerning. They are indications of a pushback from Samos island on 21 April and need to be formally investigated,” Girard said.

In the meantime, Zaga’s family has received asylum. She says she fled her home in the Nablus region of the West Bank for several reasons, but mainly to escape an abusive husband who assaulted her eldest son. She hopes to eventually reach Belgium, where her sister lives.

“I want to see my children happy, to see them going to school, eating healthy food, sleeping well and to live normally, just like other children,” she said. “To have safety and security, to have a school and home.”

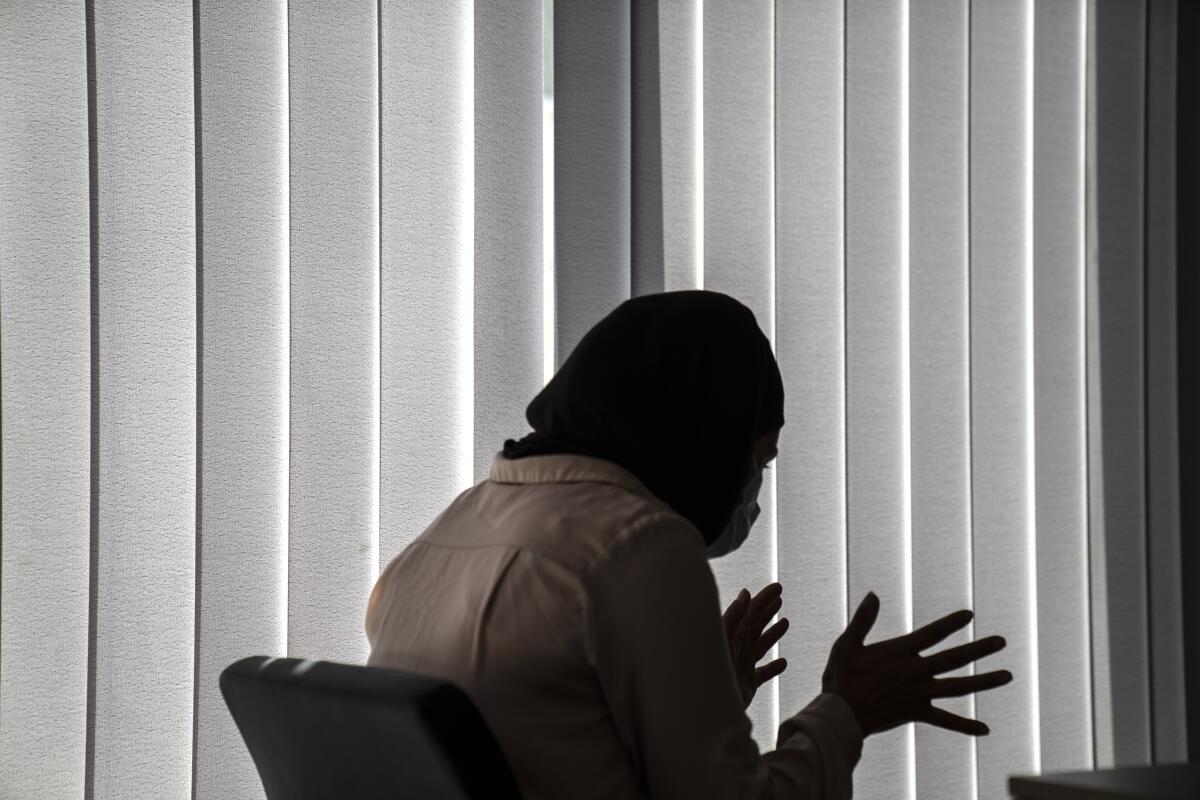

For Choulis, Zaga’s successful asylum application underscores the perils of pushbacks, which have, at times, allegedly been carried out by masked men without visible badges on their uniforms, to hide their identities.

“The fact that her asylum application was accepted shows just how dangerous it is for masked men of the coast guard or the police to judge who has the right to asylum and who doesn’t,” the lawyer said.

“We cannot leave the fate of something as important as the right to asylum to be determined in the middle of the sea or on the shores.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.