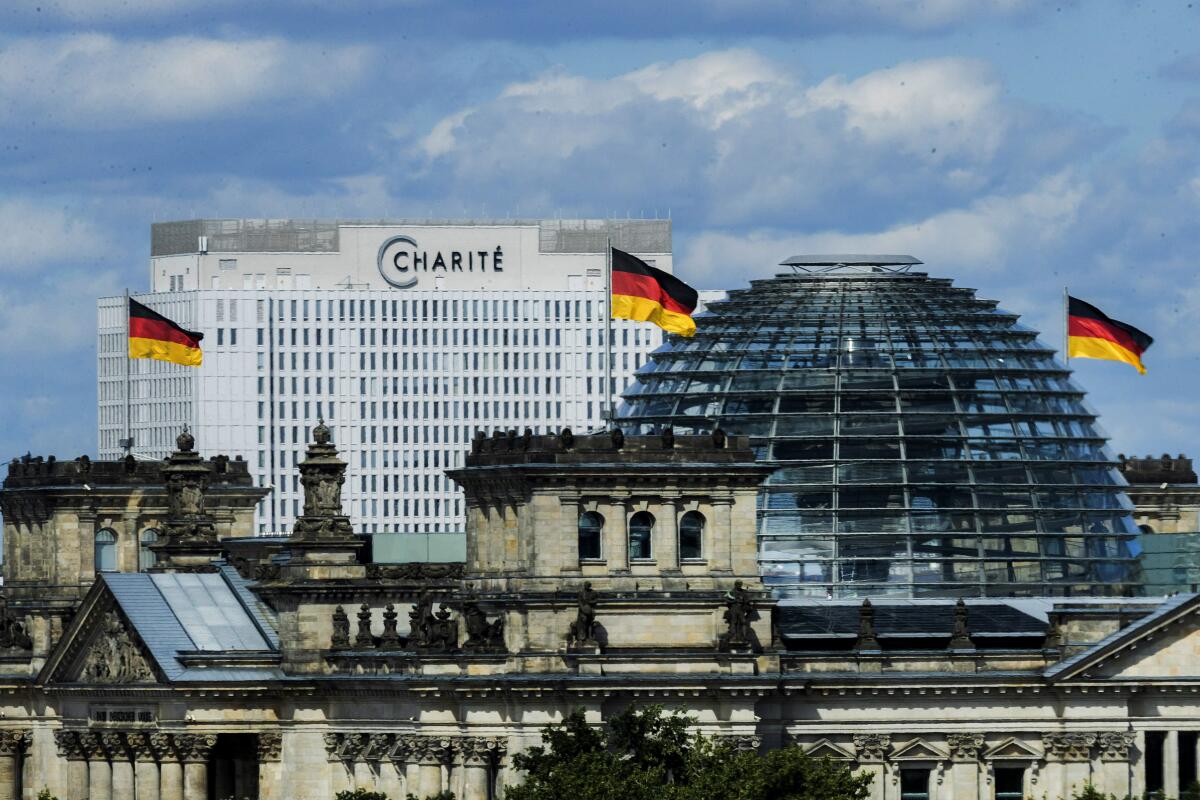

How and when will Germany form a new government? An explainer

- Share via

BERLIN — Germany’s voters have delivered their verdict, giving a narrow victory to the center-left Social Democrats over outgoing Angela Merkel’s center-right bloc. Now it’s up to party leaders to thrash out who will succeed her in the top job and with what political priorities.

Three fairly plausible new coalition governments could take shape, but the wrangling could last weeks. Here’s a look at how the process works.

What happens next?

The party with the most seats typically leads German governments, but that isn’t always the case. It can end up in opposition if other parties form a majority coalition without it. That happened in 1976 and 1980, when then-Chancellor Helmut Schmidt stayed in office although his party finished second.

There is no referee for the process of forming a new government, and no set time limit. Parties hold exploratory talks to determine common ground, and one combination of parties then moves on to formal coalition talks.

Those negotiations usually produce a detailed coalition agreement setting out the new government’s plans. That will typically need approval from at least the congresses of the parties involved. The Social Democrats balloted their entire membership in 2013 and 2018 to sign off on agreements to join Merkel’s center-right bloc as its junior partner in government.

Angela Merkel, a once-obscure scientist who claimed the global spotlight, leaves a mixed legacy as her 16-year tenure as Germany’s chancellor ends.

Once a coalition is ready, Germany’s president nominates to the Bundestag a candidate for chancellor, who needs approval from a majority of all members to be elected.

If two attempts to elect a chancellor with a majority fail, the constitution allows for a third vote and then for the president either to appoint the candidate who comes in first or to dissolve the Bundestag and hold a new national election. That has never yet happened.

When will Merkel step down?

Merkel and her outgoing government will remain in office in a caretaker capacity until the Bundestag elects her successor.

The outgoing coalition holds the record for the longest time taken for a government to be formed. The Bundestag elected Merkel for her fourth term as chancellor March 14, 2018 — nearly six months after German voters had their say on Sept. 24, 2017.

One side effect of a very long coalition-building process might be to add another aspect to Merkel’s legacy. Among Germany’s post-World War II leaders, she has served longer than all but Helmut Kohl, who led the country to reunification during his 1982-98 tenure. She would overtake him if she is still in office Dec. 17.

What parties are involved?

Four parties are potentially in play to form the new government. The outcome will almost certainly be a coalition that has a majority of the seats in parliament. Germany has no tradition of minority governments, which are generally viewed as unstable and undesirable.

The Social Democrats, under outgoing Finance Minister and Vice Chancellor Olaf Scholz, are the biggest party in the Bundestag after Sunday’s election, but even they are far short of a majority. They have 206 of 735 seats.

About 20 million German voters were expected to turn to their phones or other online devices for app advice on which candidates to pick on Sunday.

The Social Democrats want to build a coalition with the environmentalist Greens and the business-friendly Free Democrats. That’s known in Germany as a “traffic light” coalition, after the parties’ colors of red, green and yellow.

The leader of Merkel’s Union bloc, Armin Laschet, could also form a government with those two smaller parties, which is called a “Jamaica” coalition because the parties’ colors of black, green and yellow reflect the Jamaican flag.

Both “traffic light” and “Jamaica” groupings have been tried successfully in German state governments, but not at the national level.

Agreeing on either may not be easy because the Greens in recent decades have tended to ally themselves with the Social Democrats and the Free Democrats with the Union. The two parties have different priorities on fighting climate change, which the Greens want to put at the center of the new government’s agenda, and on how to handle the economy as it recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Free Democrats and Union oppose raising taxes and loosening Germany’s tight rules on running up public debt. The Social Democrats and Greens want to raise taxes for top earners and increase the minimum wage.

In Europe, the Union and Free Democrats have tended to take a stricter line on financial aid to struggling fellow European Union countries. But neither alliance is likely to be troubled by huge foreign policy differences, though the Greens favor a tougher line toward China and Russia and oppose the new Nord Stream 2 pipeline bringing Russian gas to Germany.

There is one alternative to a “traffic light” or “Jamaica” coalition: a repeat of the outgoing “grand coalition” of the Union and Social Democrats, but this time under the latter’s leadership. This combination of rivals has run Germany for 12 of Merkel’s 16 years as chancellor and has often been marred by squabbling. There is little appetite for the alliance to continue.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.