Supply chain crisis gives once invisible shipping industry record profits and new adversaries

- Share via

YIWU, China — Consider the plight of Xu Yaping’s flimsy swords and knockoff Barbies.

Exported from the International Trade City here, a wholesale market the size of 1,000 football fields, the toys for years have found their way across the world on ocean freight. But a once fast and cheap shipping network — accounting for 90% of global trade — has been upended by the pandemic and a supply chain crunch that has been roiling the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Amid a maze of cramped stalls in this bastion of globalization, Xu has watched her profits tumble: A container filled with $24,000 worth of toys headed for North America will now cost her more than 10 times the $1,250 fee she used to pay before the pandemic. Customers are canceling orders. Those remaining are buying a fraction of what they did before. Others are waiting for shipping rates to fall.

“They will say: ‘Ah, it’s expensive right now so let’s wait a couple of days,’” said Xu. “Then they’ll keep waiting, and the shipping fees will keep rising.”

Modern ocean freight has underpinned global trade for decades in relative obscurity, often beyond government regulators and hiding behind a veil of efficiency and reliability that cuts costs for storage by delivering goods “just in time” — the inventory system pioneered by Toyota and adopted worldwide. That’s no longer the case.

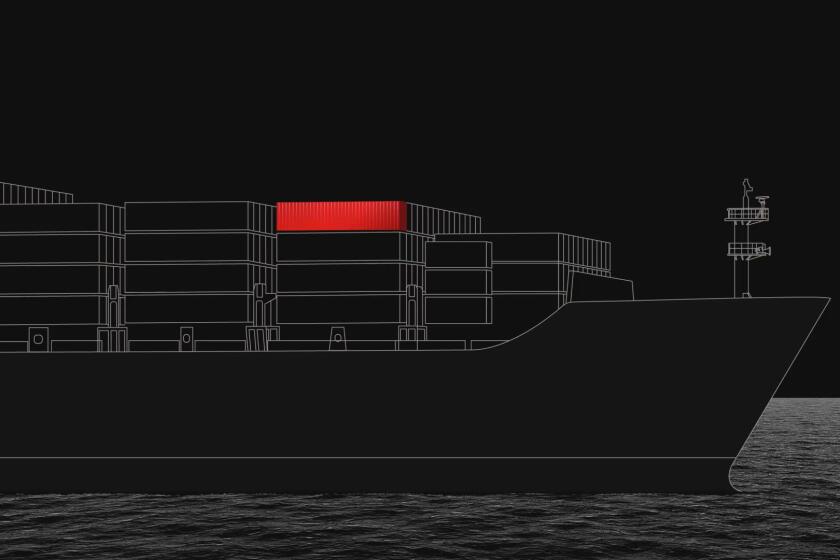

The business dominated by a handful of European and Asian players now finds itself at the center of a logistics knot that shows few signs of improving, contributing to the highest inflation rate in the U.S. since 1990 and triggering massive shortages of such diverse items as medical supplies, semiconductors, tires and toys.

It’s not a crisis of their making or one that’s hurting them financially: “These companies are making enough money in one year to cover whatever investments they’ve made in the last 10,” said Jason Chiang, director at Ocean Shipping Consultants in Singapore, a major transshipment hub. “One entire voyage is enough to earn back the cost of an entire ship. That’s like taking one trip as an Uber driver and being paid the value of the car.”

But the supply chain woes are bringing attention to an industry that for generations has raised concerns about fair competition, treatment of workers and damage to the environment. Shipping companies face a pivotal moment of either keeping the model that has made them vulnerable to boom and bust periods, or adapting to a world that will need bigger ports, greater warehouse and distribution infrastructure and more low-carbon ships. What they choose to do will probably determine how the world economy responds to the next global crisis.

“What we are going through right now ... nobody has ever seen before,” Otto Schacht, the head of sea logistics at Swiss freight forwarding giant Kuehne and Nagel, recently told Lloyd’s List, a 287-year-old British shipping journal. “It’s like the famous black swan theory. There are no black swans and all of a sudden there is a black swan. And I think one thing we realize: Things will not be as they were in the past.”

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

Shippers should hope not. An industry with an estimated 5,500 container vessels was caught unawares and flat-footed by the first COVID-19 lockdowns last year, paring their sailing schedules and disrupting the positioning of their fleets. When Americans flush with stimulus cash embarked on a spending spree a year later, there weren’t enough ships in place to meet the explosive demand.

Exporters, freight forwarders and retailers started outbidding one another for a dwindling amount of space aboard cargo vessels from Asia. Some companies like Amazon, Walmart and Costco resorted to chartering their own boats. Every able container ship was pulled into service in a Dunkirk-like scramble to reach U.S. consumers.

When the flotilla arrived in Southern California, the vessels found too few port berths and workers, warehouse space filling to capacity, and not nearly enough truck drivers and chassis to handle the containers quickly piling up. An unprecedented 70 ships or more are now regularly bobbing in the waters outside the busiest port complex in the U.S. — a bottleneck expected to outlast the busy holiday season.

“Everything is so out of its normal balance it will take more than a year for global logistics to unwind,” said Peter Sands, chief analyst at Xeneta, a Norwegian analytics firm for the freight industry.

Making matters worse, a container shortage has plagued Asian exporters. The kind of steel boxes that carried Xu’s swords and knockoff Barbies across the ocean are returning to Asia at a rate of only one for every four arriving in the U.S., according to data provided by IHS Markit.

The logjam has sent shipping costs to record highs. The Shanghai Containerized Freight Index, a closely followed gauge measuring the cost of shipping from Chinese ports, soared 449% in early October compared with the same period two years ago.

“Just a perfect storm,” said Nathan Resnick, president and co-founder of Sourcify, a San Diego-based firm that links U.S. entrepreneurs to factories in Asia. “Small- and medium-sized businesses are struggling to fathom paying this much for freight.”

It hasn’t been bad for everyone. The cascade of problems has resulted in extraordinary earnings for shipping giants like Denmark’s Maersk, France’s CMA CGM, Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd and China’s Cosco, which were on track to reap a decade’s worth of gross profit in just one year.

Drewry, a maritime research consultancy, estimates container shipping lines could collectively take in up to $100 billion in net earnings by the end of 2021, tripling a forecast from March and putting the companies in the same league as corporate behemoths like Apple. Sleek they are not, but the ships, loaded and lumbering across the seas, are a reminder that old world ways are indispensable to the new world order.

Chiang said times were so good that a major freight liner invited suppliers, customers and other partners to a typically austere event to mark a recent quarterly earnings report and gave attendees GoPro cameras as gifts.

Though prices will eventually fall, shippers are seizing on the current chaos to lock customers into long-term contracts, a trend that puts more pressure on low-margin exporters like those in International Trade City in Yiwu. “Small businesses like us don’t have that cohesive power,” said Xu, the toy exporter.

The consequences of that reality are felt across this sprawling market where floors are split into sections dedicated to cosmetics at one end, buttons and zippers at the other. Animal slippers, beaded necklaces, keychains and disposable razors are lined in rows and ready to be sold for just a few cents apiece.

“Without long-term, stable orders, we probably can’t do this,” Xu said.

They’ve been stuck for months on cargo ships now floating off Southern California. They’re desperate

On ships caught in the huge floating traffic jam off L.A., seafarers with scant access to vaccines have been stuck in limbo for months. Unions tell of despair and violence.

The sudden fortunes of ocean freight lines have led to accusations of profiteering, drawing scrutiny from governments and manufacturers. British trade groups are calling on the country’s Competition and Markets Authority to investigate “cartel-like” pricing in the shipping industry.

The Biden administration signed an executive order in July that encouraged the U.S. Federal Maritime Commission to stop the shipping industry from charging U.S. exporters “exorbitant fees” for the time their freight took to be loaded and unloaded.

“In 2000, the largest 10 shipping companies controlled 12% of the market,” the White House said in a statement. “Today, it is more than 80%, leaving domestic manufacturers who need to export goods at these large foreign companies’ mercy.”

Critics say the industry’s consolidated power and the lack of government oversight have created blind spots that allow shipping lines to slow their costly transition away from sulfur-spewing bunker fuel and avoid improving working conditions for seafarers so that hundreds of thousands aren’t stranded aboard boats because of COVID-19 border closures.

The United States and 18 other countries on Wednesday committed to curbing emissions from the shipping industry, which accounts for 3% of the world’s CO2 emissions. The pledge, which came during the United Nations global climate summit, intends to eventually move freighters away from fossil fuels to cleaner energy to create zero-emission shipping lanes.

The new financial might of shippers is unusual for a business that’s notoriously fickle and tied to the whims of global markets. Building a cargo vessel can take years, which is why the industry often orders too many new ships when times are good and is saddled with a glut when times are bad.

“The history of this industry is up and down,” said Willy Shih, a professor at Harvard Business School who studies supply chains. “When there’s too much capacity, everyone loses their shirt. They’re making up for all those unprofitable years now while they can, but I don’t think it’s sustainable.”

Order books for new vessels are filling up, analysts say, but shippers are also pouring money into other areas. CMA CGM said Wednesday it was paying $2.3 billion to buy a full stake in the third-largest terminal at the Port of L.A. Maersk is buying jetliners and expanding its air-freight and land-freight businesses, part of a wider strategy to offer the door-to-door services provided by the likes of DHL, UPS and FedEx. The world’s largest container shipping company has also placed orders for eight vessels that can run on carbon-neutral methanol as it tries to meet its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Calls for a more resilient and greener supply chain in a post-pandemic world are likely to continue to raise questions about shipping.

“I hope the attention, such as it is, is lasting,” said Rose George, who detailed her five weeks aboard a container ship examining the human and environmental toll of shipping in a book titled “Ninety Percent of Everything.”

“Anything that makes us think about where things come from, and what it costs the world to supply everything all the time, just in time, can only be a good thing,” she said.

Times staff writers Pierson reported from Singapore and Su from Yiwu.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.