Arizona executes first prisoner in nearly eight years after Supreme Court declines to hear case

- Share via

FLORENCE, Ariz. — An Arizona man convicted of killing a college student in 1978 was put to death Wednesday after a nearly eight-year hiatus in the state’s use of the death penalty brought on by its last execution, a nearly two-hour episode that critics say was botched.

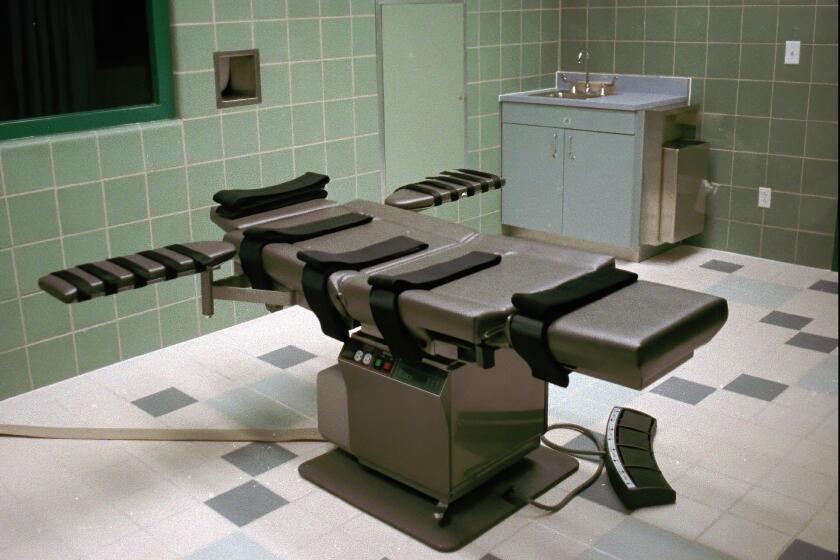

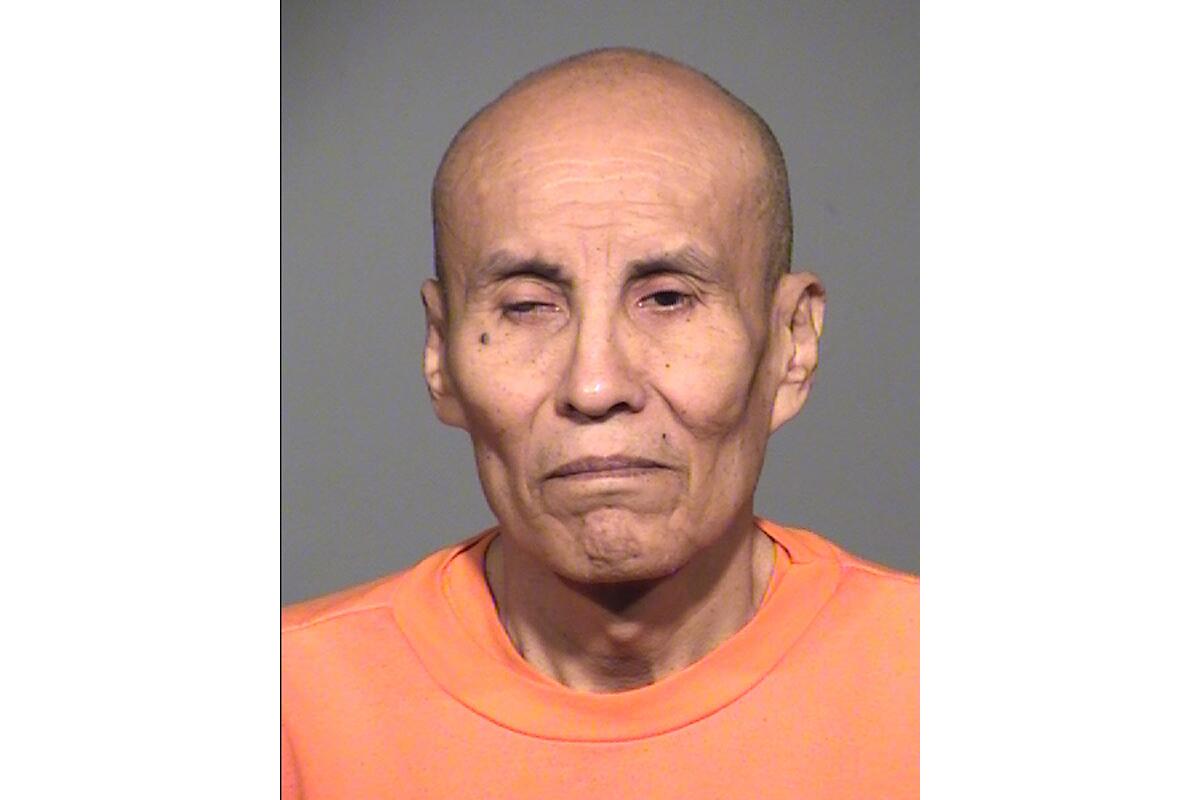

Clarence Dixon, 66, died by lethal injection at the state prison in Florence for his murder conviction in the killing of 21-year-old Arizona State University student Deana Bowdoin, making him the sixth person to be executed in the U.S. in 2022. Dixon’s death was announced late Wednesday morning by Frank Strada, a deputy director with the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry.

The medical team had difficulty finding a vein to administer the lethal drugs, first trying his arms and then making an incision in his groin area. That process took about 25 minutes.

After the drugs were injected, Dixon’s mouth stayed open and his body did not move. The execution was declared completed about 10 minutes after he was injected.

In the final weeks of his life, Dixon’s lawyers made last-minute arguments to the courts to postpone his execution, but judges rejected the argument that he was mentally unfit to be executed and had no rational understanding of why the state wanted to put him to death. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected a last-minute delay of Dixon’s execution less than an hour before his execution began.

Dixon earlier declined the option of being killed in Arizona’s gas chamber that was refurbished in 2020, a method that hasn’t been used in the U.S. in more than two decades.

Shortly before Dixon was executed with pentobarbital, Strada said he declared: “The Arizona Supreme Court should follow the laws. They denied my appeals and petitions to change the outcome of this trial. I do and will always proclaim innocence. Now, let’s do this [expletive].”

And as prison medical staff put an IV line in Dixon’s thigh in preparation for the injection, he chided them, saying: “This is really funny — trying to be as thorough as possible while you are trying to kill me.”

Leslie James, Bowdoin’s older sister and a witness to the execution, told reporters after it was conducted that Deana Bowdoin had been due to graduate from ASU and was planning a career in international marketing. James described her sister as a hard worker who loved to travel, spoke multiple languages and wrote poetry.

She characterized the execution as a relief but criticized how long it took to happen: “This process was way, way, way too long,” James said. Dixon had been on death row since his 2008 conviction.

The drop in the number of executions this year was due in part to the pandemic but also came during a decline in support for the death penalty.

The last time Arizona executed a prisoner was in July 2014, when Joseph Wood was given 15 doses of a two-drug combination in a drawn-out execution that his lawyers said was botched. Wood snorted repeatedly and gasped more than 600 times before he died, and an execution that normally would take 10 minutes to complete lasted nearly two hours. The process dragged on for so long that the Arizona Supreme Court convened an emergency hearing during the execution to decide whether to halt the procedure.

States including Arizona have struggled to buy execution drugs in recent years after U.S. and European pharmaceutical companies began blocking the use of their products in lethal injections.

Authorities have said Bowdoin, who was found dead in her apartment in the Phoenix suburb of Tempe, had been raped, stabbed and strangled with a belt.

Dixon, who lived across the street from Bowdoin, had been charged with raping Bowdoin, but the charge was dropped on statute-of-limitation grounds. He was convicted of her murder, however.

In arguing that their client was mentally unfit, Dixon’s lawyers have said he erroneously believed he would be executed because police at Northern Arizona University wrongfully arrested him in another case — a 1985 attack on a 21-year-old student. His attorneys acknowledged he was lawfully arrested then by Flagstaff police.

Despite an entreaty from Gov. Gavin Newsom, the California Supreme Court has refused to overturn hundreds, if not all, death sentences in the state.

Dixon was sentenced to life in prison in that case for sexual assault and other charges. DNA samples taken while he was in prison linked him to Bowdoin’s killing, which at that point had been unsolved.

Prosecutors said there was nothing about Dixon’s beliefs that prevented him from understanding the reason for the execution and pointed to court filings that Dixon had made over the years.

Defense lawyers have said Dixon was repeatedly diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, regularly experienced hallucinations over the last 30 years and was found not guilty by reason of insanity in a 1977 assault case in which the verdict was delivered by then-Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor, nearly four years before her appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. Bowdoin was killed two days after the verdict, according to court records.

Another Arizona death row prisoner, Frank Atwood, is scheduled to be executed June 8 in the killing of 8-year-old Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in 1984. Authorities say Atwood kidnapped the girl.

The child’s remains were discovered in the desert northwest of Tucson nearly seven months after her disappearance. Experts could not determine the cause of death from the bones that were found, according to court records.

Arizona now has 112 prisoners left on death row.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.